The Jerwood Painting Fellowships provide critical support for exceptional painters embarking on their professional careers. The third edition ran from 11 May until 19 June 2016, exhibiting work by Fellows Francesca Blomfield, Archie Franks and Dale Lewis. My first related post was an interview with Francesca Blomfield. This post looks at how inspiration and memory fuses and mutates in both Archie Franks and Dale Lewis’ artistic practice, drawing out how a collision of past and present manifests itself in both sets of works.

Perhaps contrary to first glance, and despite their idiosyncratic stylistic differences, Archie Franks’ and Dale Lewis’ paintings compliment each other. Images of crisp packets, cider cans, park benches and fairground rides abound. Time stands still on Archie’s baroque clocks and stopwatches. Dale’s characters attend funerals, smoke cigarettes, or engage in sexual acts. There is something quintessentially British, yet still strikingly individual, about both sets of paintings. My opinion is that no work can truly exist in a vacuum, and these canvases are particularly inextricable from their creators. Inspired by canonical movements in art history, such as the Renaissance or the Baroque, both artists have subverted and used these motifs in contemporary ways. They are not necessarily interested in the contrived dichotomy of ‘high art and low culture’, but instead are infusing these classical forms and structures with their own memories and experiences of everyday life. “Painting is just another way of keeping a diary”, said Pablo Picasso. Using a short email conversation with Archie Franks, and comments made by Dale Lewis when in conversation with Norman Rosenthal at the gallery on 4 June, this piece intends to draw out particular complimentary inspirations, references and ways of working.

Archie Franks

Using Baroque and Rococo motifs…

“The baroque and rococo periods, alongside simply signifying decadence and overt ornamentation, appear to me to be the two centuries where art goes from being essentially church based propaganda to being an overt portrayal of an internal private dream. The very best artists of the Rococo era are fundamentally dealing with illusion, fantasy, madness and psychology. Baroque painting deals with illusion and psychology too, looking at drama and staging. These are the things that appeal to me. Also, there is a link with these themes and the horror movies I like. The references are a collection of memories, so it’s not a point about ‘high art’ per se, but about connecting your world with art history, making your own small dramas and life part of something larger. I also find it interesting to draw out the more interesting aspects of the Rococo, highlighting the similarities with the contemporary world.”

The particular subject matters explored in the exhibition…

“Memory, fiction, illusion, authenticity, my own life and history, and how those things relate to painting. Some works are almost diaristic in their literal relationship to my life, while others have more of a metaphorical relationship to my ongoing concerns and themes”

On Caravaggio and Fragonard…

“I try and steal things from Caravaggio and Fragonard. Caravaggio’s still life Basket of Fruit and Fragonard’s Le Petite Parc have been staple points of reference for some time. With Caravaggio, he wants you to buy the illusion he creates as genuine. He wants that basket to inhabit your space, to almost fall into your world. I find that totally fascinating. I love the dreamy atmosphere in Fragonard, the sense of unreality. There’s a palpable sense of intoxicating sexuality, wildness and dreaming with some of his work that I want to steal and re-establish as my own somehow. The ‘petite parc’ picture is set in Rome. It looks like a park I used to walk through every day, even though it’s a different Roman park. I liked the idea that I was somehow in a similar setup to him but centuries apart (he did a residency at the French Academy, mine was at the British one). Essentially, Rome gets into your blood. I got really interested in De Chirico while in Rome, and begun to see his work more and more as a response to the city. I think setting is important for me, and living in Rome made me consider setting the work in a more dreamy, unreal space, because that’s how that city feels to inhabit.”

Use of paint…

“The way I paint is very material. I just want the physicality of the medium to be apparent and show through. It also alludes to an idea of ‘authentic’ gesture. For me, it’s important to exploit the material properties of paint; otherwise you’d begin to question ‘why use paint at all?’ The colour for the most part, and the material, is mostly all about creating a particular atmosphere. Atmosphere is really the only aspect of the work that actually matters. All the other components should simply be in aid of creating the atmosphere you want.”

The collision of past and present…

“The past and present colliding and collective and personal memories form my motifs, and I like trying to mix those things up. I guess part of my point is that the past is actually the present. There is only this moment, and this moment is created out of the residue of the past, personal, collective, cultural. Misremembered, misunderstood and actual histories coexist simultaneously now.”

Dale Lewis

Memories of growing up in Harlow…

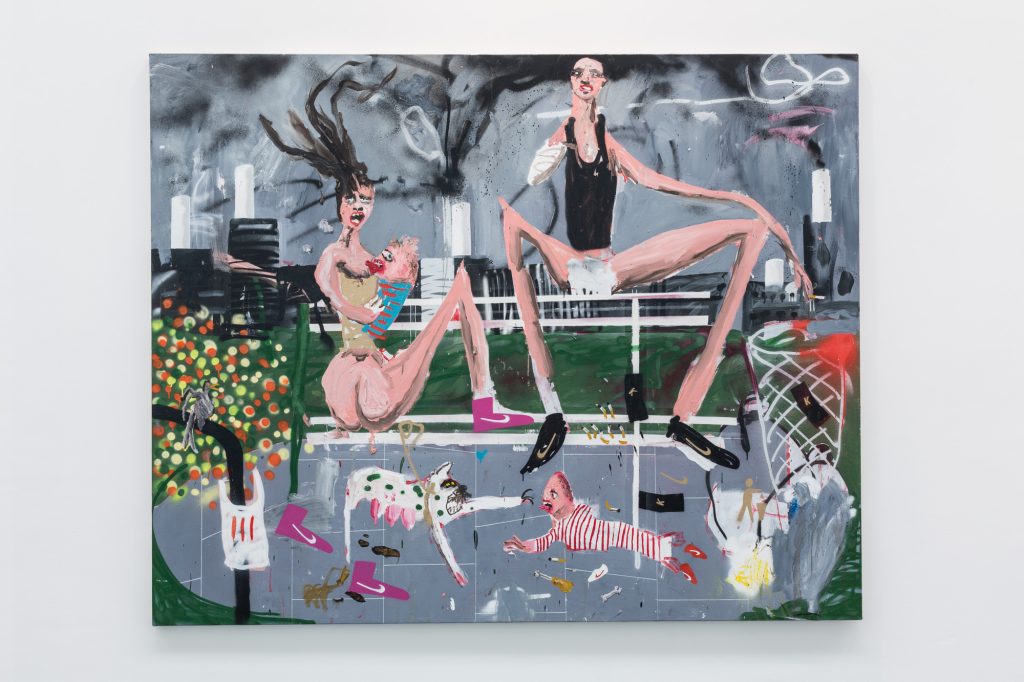

The painting Chicken Wings (2016) is based on Henry Moore’s Harlow Family Sculpture (1953-4). Moore’s sculpture was an emblem of the visionary post-war town in Essex, also known as ‘sculpture town’. Lewis was familiar with the sculpture, seeing it often throughout his youth and adolescence; “Someone threw a brick at the baby’s head and it was missing for fifteen years”. The smoking chimneys in the background of the painting represent small industry, whereas the use of the park bench and the symbolism of cans of cider and Nike trainers can be seen as a more satirical viewpoint on commonplace events. Dale’s everyday observations feed into the work, re-made louder and brighter. Taste is eschewed for humour and expression. The story behind Acid Man’s Funeral (2015) is also derived from Harlow. The ‘Acid Man’ was a legendary figure known by generations as someone who took so much LSD in the 1980s that he had never come out of his trip. After finding out that this character was dead, Dale painted a lurid scene of the Acid Man watching his own funeral. The basis of this composition illustrates how associations and decade-old stories can inform the content of paintings years later. Working from memory often means that the paintings are warped versions of reality, amalgamating emotional and visual sources.

Creating works in one day…

Although the subject of work might be generated from a backlog of personal memories and experiences, the paintings are always made in one day. It’s important for Dale to paint them in one sitting and not go back to them; “It’s like a love affair, they’re like one night stands. You have a really great time making it but then you’re on to the next one”. Despite keeping a sketchbook with him at all times, these large canvases are only nominally and briefly sketched out on an A5 piece of paper. In order for the distortion of reality to dominate, no photographs are worked from.

On being inspired by the Old Masters…

Despite an affinity with Basquiat or early Hockney, Dale’s use of composition is often based on the Old Masters, who he regards as “tried and tested, safe”. Often vising the National Gallery or searching for obscure Renaissance paintings online, he tends to be inspired by the small bottom panels on altarpieces, responding to their flatness and amateur charm. Elements of Champagne (2016) were derived from an interest in the Turin Shroud. Sunday Roast (2016), which depicts an orgy, is derived from the Italian Renaissance ‘Battle of the Nudes’ (1465-75). Engraved by Antonio del Pollaiuolo, the print shows ten naked men in combat. The implicit circular sexuality of the image is exacerbated in Dale’s painting, although he commented that perhaps it isn’t just about sex, but also about “a painter in a studio working out how to do a painting and moving around the canvas”.