“…it was not there, in the kitchen, that I began, really, to love you

Ah, Momma,

It was where I found you, hidden away, in your ‘little room,’ where

your life and the power, the rhythms of your sacrifice, the ritual of your

bowed head, and your laughter always partly concealed, where all of

you, womanly, reverberated big as the whole house, it was there that I

came, humbly, into an angry, an absolute determination that I would,

one day, prove myself to be, in fact, your daughter”[1]

‘Ah, Momma’ by June Jordan, 1975

June Jordan was a Jamaican-American writer whose work encompassed poetry, essays and children’s fiction; exploring personal and collective issues of race, gender and representation. ‘Ah, Momma’ (1975) is a love letter to Jordan’s mother, when she had this moment of recognition, a kind of consciousness-raising, of everything her mother had sacrificed for her. At this moment, she became more deeply aware of her love for her mother on discovering her truth, in her full form as a woman, independent from notions of the home, of being a wife and motherhood; another person outside of what she had always known.

During her enquiry into her own family photo album, Italian Togolaise artist Silvia Rosi discovered a photograph of her mother working at the market in Lomé to save up money to move to Italy with Rosi’s father in the late 1980s, where the artist was born. Jordan’s ‘little room’ becomes Rosi’s photograph; an entry point into a deeper understanding of her mother’s life before she moved to Italy, allowing for a deeper understanding of her West African heritage. Encounter exhibits staged self-portraits in both black and white and colour photographs and moving-image works, and acts as a homage and contribution to Rosi’s family photo album which she has here fictionalised, playing with oral histories as told by her mother. The family photo album will be considered as a site of love that is intrinsically bound up with absence and loss, with the missing parts of the story that cannot be contained in a photograph. Similarly to Jordan’s love letter to her own mother above, elements of Encounter could be interpreted as a love letter to Rosi’s mother, whom the artist cites as her muse. This positioning of the maternal will be unpacked further as an act of love within this essay and becomes the bridge that connects Rosi with Togo, as fragments of her cultural heritage were misplaced as a result of her family’s migration to Europe.

“Photography thereby compelled me to perform a painful labor; straining toward the essence of her identity, I was struggling among images partially true, and totally false.”[2]

Roland Barthes

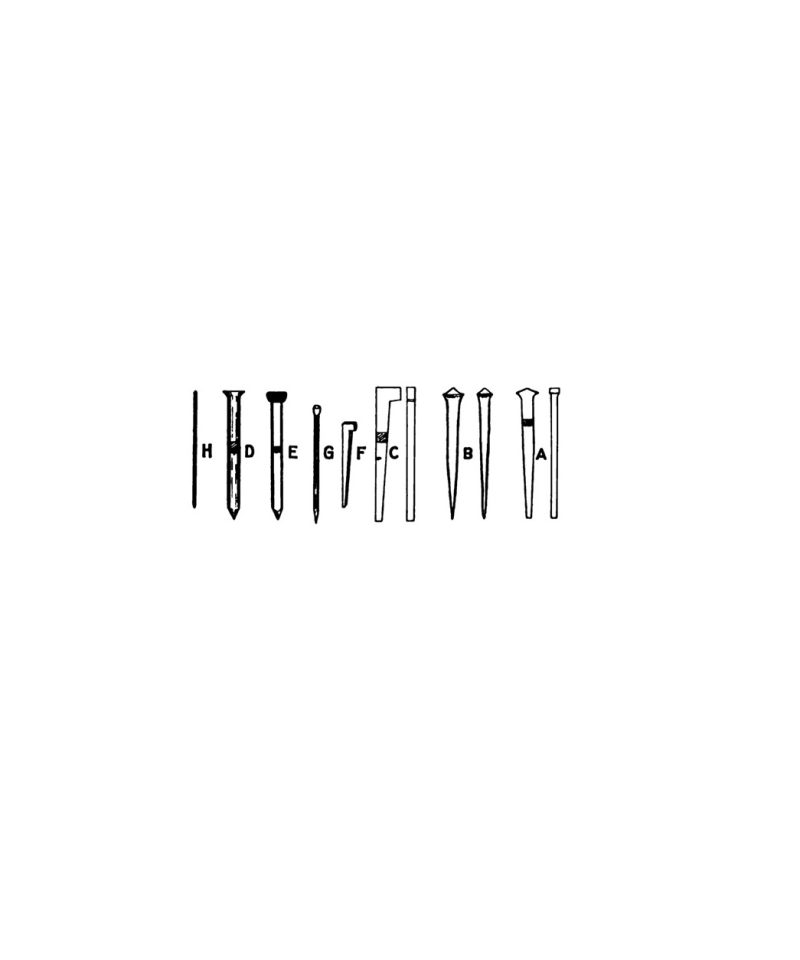

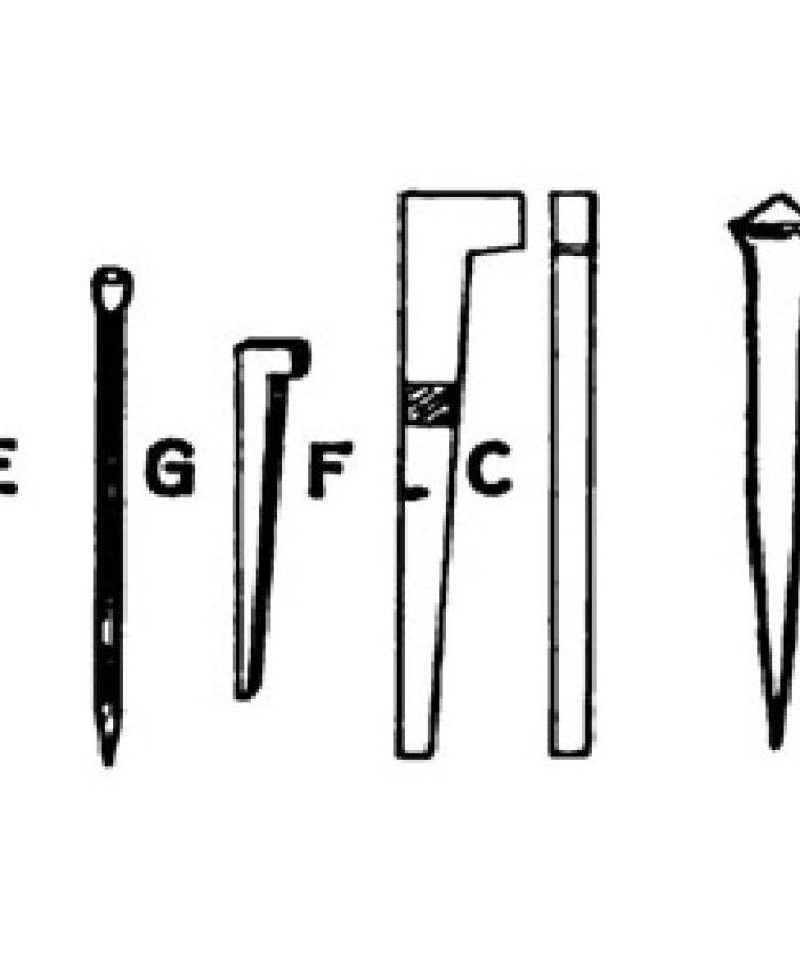

Roland Barthes’ seminal book Camera Lucida (1981) traces the writer grieving his mother whilst trying to search for the ‘real’ her within a collection of photographs in an attempt to unpick the authentic essence of photography. He talks about the photograph as being paradoxical in nature, having the capacity to revivify something or someone, creating something that is simultaneously dead and alive. His quest is complete when he discovers what he titled the Winter Garden Photograph taken when his mother was five years old with her brother, in which she still emanated the gentle kindness that Barthes had remembered her for, which he considered the core of her personality. When Rosi first discovered the images of her parents that had been taken in the photography studios of Togo, there was a feeling of dissonance as she recognised her family members but was unfamiliar with the way that they were depicted. This prompted the artist to research the West African studio portrait through work by photographers such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta. Although the moment that Barthes and Rosi discovered their mothers within the image differs, they both position the maternal in the centre of their searches, making their mothers their muse. Barthes was compelled to “perform a painful labour.”[3] He mourned for and missed his mother, revisiting photographs of her that are insufficient in bringing her back to him, to life. Each failed attempt amounted to another agonising loss as he yearned for her: “it was not she, and yet it was no one else.”[4] The context of Rosi’s search is undoubtedly different; rather than enacting this painful labour of loss, she performed labours of love – from her devotion to reconnecting with her mother’s personal history to embodying the personas of her parents. One of these acts is in her learning of the head carrying technique, a matrilineal skill that is traditionally used by the market women of Togo to transport their goods and that Rosi’s mother had used; however, this custom had been lost in Rosi’s immediate family due to their migration to Italy.

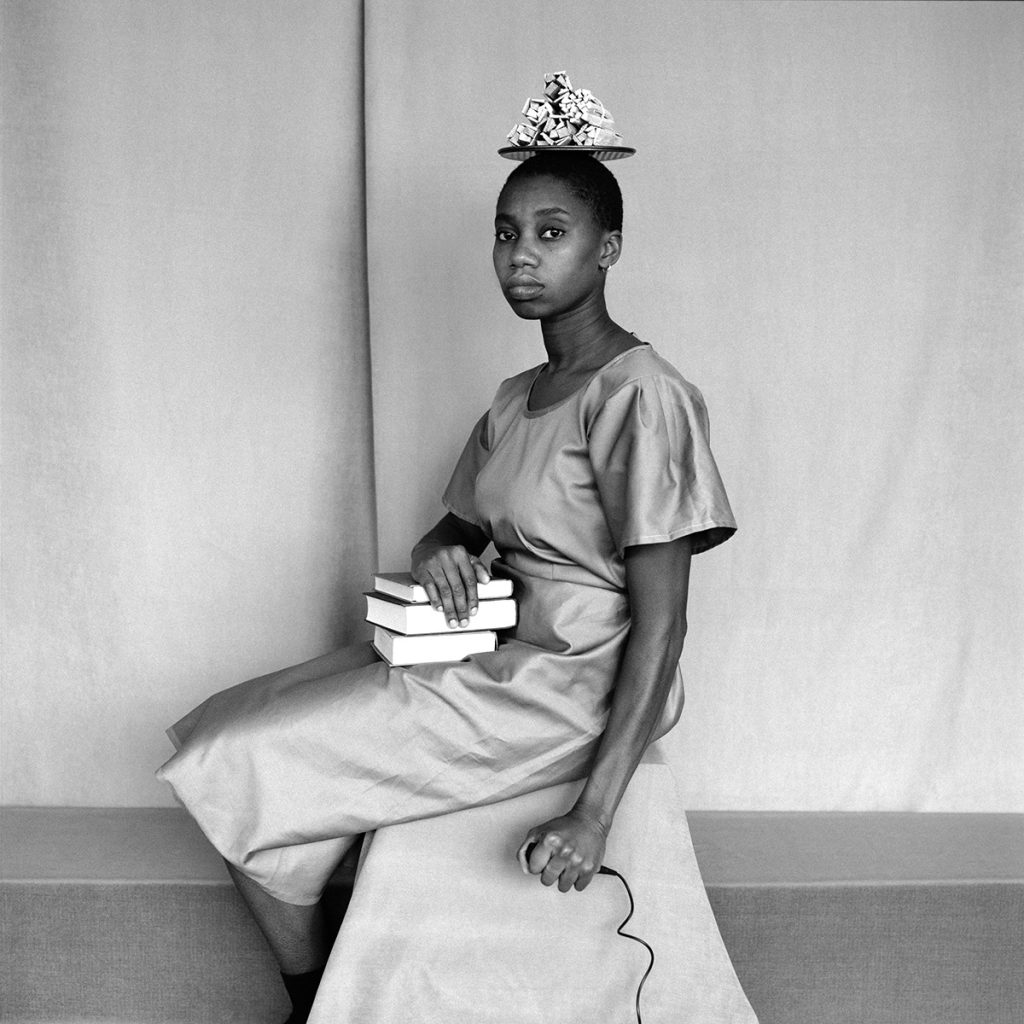

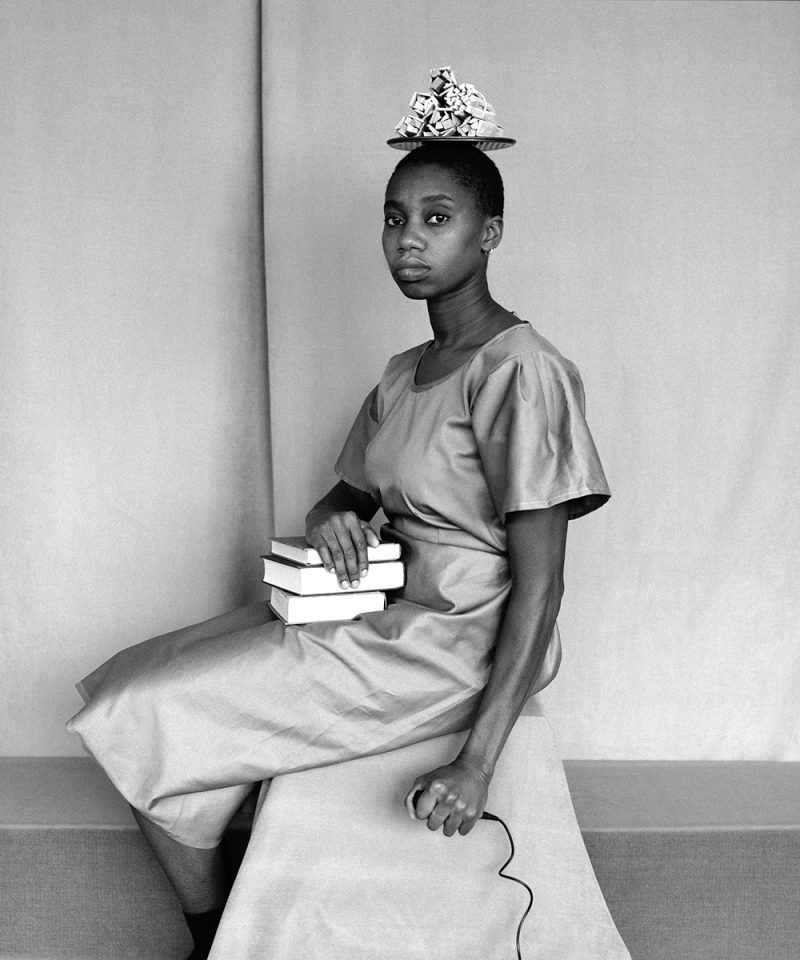

The first photograph on entering the gallery space is Self Portrait as my Mother in School Uniform, a black and white image of the artist sitting sideways on a stool cloaked in material, her body slightly turned to face the camera, her eyes looking directly into its lens. There is a certain stillness, an ease with which she is holding this pose, whilst effortlessly balancing a plate of toothpicks on top of her head. One hand gently holds a pile of books propped on her lap, as her other hand and forearm clench the camera shutter release remote; its cable trailing off into the bottom edge of the photo. A bench shrouded in cloth cuts into the horizon of the image and a fabric-covered backdrop forms the background. Below the photograph is a framed text that repeats itself and places the word ‘toothpicks’ in bold:

“She worked as a market seller from a really young age to support her mother. She would leave the house early in the morning with a tray of toothpicks carried on top of her head. She walked around the neighbourhood shouting loudly to attract customers’ attention. After selling for about an hour she would go home, bathe, wear her uniform and walk to school with her sister.”

By positioning this as the first image in Encounter, Rosi reflects the early days of her mother’s life as a young girl and the start of her occupation as a market seller. This placement brings the viewer through the accompanying works on a journey as the story of her mother is unpacked chronologically within the show. It foregrounds the importance of the market place in Lomé, as a community hub and where women form the majority of the workforce as market sellers and it is where Rosi would regularly spend time during her visits over the past year for the research and development of this project, where she would follow and document the female traders, re-visiting a space once occupied by her own mother. When Rosi first went to the market to observe it, she was unable to communicate with the local people and was treated with suspicion, especially due to the camera in her hand prompting people to suspect that she was a journalist. However, when she returned with her mother, she was more easily accepted by the market women, enabling her to see more closely the way that they worked. The market, and the women that trade within it, become a muse for Rosi: it is symbolised by the juicy red tomatoes in Self Portrait as my Father that have been precisely stacked into triangles as they would when making a purchase at one of the market’s stalls. The significance of the market is further expressed by Rosi’s deconstruction of the head carrying technique, which the women of the market use to carry heavy loads of goods to sell. The symbol of head carrying is employed as a strategy to evoke both the struggles of the market and the struggles of migration, which is obscured by the staged nature of the family photo album. The marketplace for Rosi has become a metaphor for struggle and migration within her practice and by incorporating specific objects that are commonly sold at the market, they are transformed into symbols to illuminate this metaphor. Other props, such as the telephone or radio, are featured as symbols throughout other self-portraits in the series, creating a rich visual language within the work.

Not only has Rosi positioned her mother as her muse within this project, she has embodied her – becoming her to perform these histories, whilst simultaneously performing herself – hence declaring each image as a self-portrait as her mother; neither purely becoming her mother (nor herself). This kind of doubling echoes the repetition and emphasis of specific words within the accompanying texts for some of the works. It reflects Rosi’s performance as both photographer and subject, and the seriality that the self-portraits form. Rosi’s body becomes the medium through which she is enacting these histories that have been told to her by her mother, and her interpretation allows them to become simultaneously personal and universal. This performance of an identity evokes a reproduction of the self. Stuart Hall defines identity as “not a set of fixed attributes, the unchanging essence of the inner self, but a constantly shifting process of positioning… identity is always a never-completed process of becoming – a process of shifting identifications, rather than a singular, complete, finished state of being.” Rosi is reproducing a fragment of her mother’s identity and inevitably a fragment of her own, playing with fact and fiction to create something that is not wholly true but not wholly false either, resonating with Hall’s argument for the changeability of identity. As we have journeyed through the representations of her mother’s experiences within Encounter, the literal and physical person within the photographs remains Rosi and is therefore in a sense unchanged, but the identity she performs shifts alongside the chronology of events and with the different elements of her mother that the artist is playing with.

Alain Badiou argues in his book In Praise of Love (2012) that love has become feared or eroded due to the development of communication technologies and he advocates for the importance of love. Although he is most directly referring to romantic love between two partners, he asks: “what kind of world does one see when one experiences it from the point of view of two and not one? What is the world like when it is experienced, developed and lived from the point of view of difference and not identity? That is what I believe love to be.”[5] Through the becoming of multiple identities, through the performance of both herself and her mother within Encounter, Silvia Rosi demonstrates this act of love in her representation of her mother, by reframing her mother as her muse within her fictionalised family album.