‘Camp’ Susan Sontag famously claimed ‘sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman but a ‘woman.’’ This claim is not beyond dispute but if we accept it, do we accept that the dissonance, the schism between the authentic un-parenthesized and some tawdry approximation is real but moot, or do we take it to be inherently bogus?

Sontag’s proposition of camp as ‘Being-as-Playing-a-Role’ and ‘the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theatre’ sounds not unlike Judith Butler’s theories on the performative constitution of gender. If that correlation is sound, then the emancipatory potential of camp lies in its critique of essentialism. It makes a nonsense of monolithic, ‘biologically determined’ identities and the putative norms and regulations entailed. All lamps are ‘lamps’, all women ‘women’ and all men ‘men.’

What about its reactionary potential of camp? Does it operate under the same logic whether debunking the founding myths of power or supporting them? With a sleazy two-bit narcissist now hawking his wares from the very apex of Western power, some stability of consensus on what constitutes a ‘real’ administration, ‘real’ leadership, or ‘real’ freedom might be welcomed. But artifice in the service of the power – especially in the neoliberal metropolis – is felt at a more intimate proximity than the global political stage. It’s felt in Formica, brittle veneer, black mould in crown moulding. Or rather, it’s felt in the gulf between such stingy details and the ubiquitous aspirational jargon of the market.

The vernacular of the property market has a camp uniquely its own – a transparent pitch profoundly at odds with lived experience. It’s characterised by ersatz cosmopolitanism and a chronic overuse of words like ‘luxury’ and ‘stunning’. It’s presence in cities like London is total. To the unfamiliar it may appear that the phenomenon of London’s sprawl – all urban sprawl for that matter – is concentric; that the densities of economic activity or population radiate in bands from the centre, through the inner city, to the suburbs, its Londonness most concentrated in zone 1, least so in zone 6. To me, though, it appears more rhizomatic. Clusters of former semi-rural villages extended their primordial tendrils until a dense fibrous mesh formed. It assimilates the peripheries, forms bubbles of its own hinterland, kneads them into the centre like dough. Cut off a chunk of London and what you have is not a fragment of the whole (the whole, as a consequence, being less ‘London’) but rather, you have another London in microcosm, as ‘London’ as the first. The rentier economy is attentive to this and ensures that living costs have a plateau below which they don’t drop even if standards do.

Returning to Sontag, the ‘lamp’ rather than lamp has prompted me to think about domestic appliances. I own relatively few and categorically no substantial furnishings. Given frequent changes of address, it makes sense. What I have at my disposal tends to come with the property. I’ve lain temporary claim to many a sofa upholstered in brown velour – the emblematic fabric of rental – but I’ve never owned one and find the idea of actually purchasing one seems faintly absurd. Brown velour sofas are not for buying – they are simply always there to remind you that this is not truly your home. There’s a special kind of estrangement that comes with being domiciled in a space provisionally one’s own yet manifestly not – an unhomeliness. It’s deliriously dramatized in gothic narratives like Roland Topor’s ‘The Tenant’ – adapted to screen by Roman Polanski and retrospectively batched alongside the similarly themed ‘Repulsion’ and ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ as the Apartment Trilogy.

The entirely fabricated scarcity in the capital’s housing generates a miasma of anxiety. Cash-strapped millenials visibly squirm from it. It casts a pall over every arduous living arrangement, every dreaded utility bill, and every sinking heart. Guardianship schemes must have appeared promising to would be occupants and godsent to freeholders when they first emerged. No barely habitable, fit-to-raze shithole must go un-monetized. Not to lose money on a nominally derelict space is boon enough. Turning a profit, modest though it may be relative to its potential, is better still, but good enough is never quite enough. To the licensee (this title, in its distinction from tenant, is crucial to the expedition of notice-to-quit procedures along with other conveniences of debatable legality) it is, if not entirely a win-win situation, then at least an advantageous compromise under duress. With mounting disequilibrium in that already top-heavy relationship, fees nearing parity with rents and a proliferation of horror stories about occupants being treated like serfs, enthusiasm for the schemes has soured significantly.

I’m not certain what type of agreement Ben Burgis and Ksenia Pedan’s place is held under, but you should visit anyway – Victoria Deepwater Terminal Estate. It’s a quirky, bohemian and edgy split-level sewer conversion. An exciting innovation that refuses to halt at warehouses or even railway arches. For want of imagination developers have left disused waste and drainage systems fallow long enough. This won’t do for London’s art-set – to meet the housing needs of creatives you need to think like them; be resourceful, unorthodox and fun – let’s fill this town with artists, at street level and below.

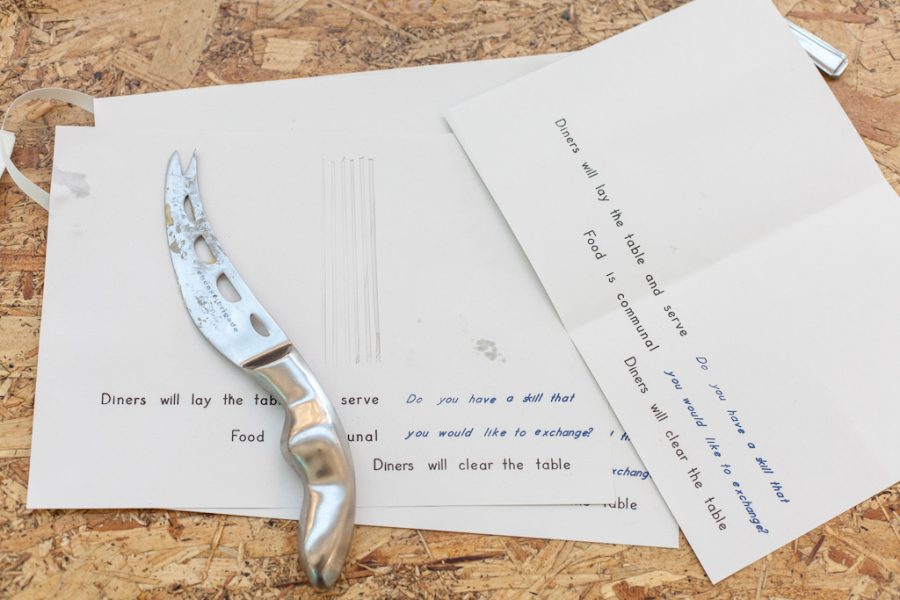

The office of the agency selling or letting the sewer is right outside it – literally, not as a narrative. It’s just scenography set up with a keen eye for the truest, most tellingly inane detail, like the chilled bottles mineral water; that ludicrous mark of antiseptic conviviality. Performers Adam Christensen and Keira Fox were there one Friday night in their capacity as ‘agents’ – looking smart, all business casual, just like real agents. The tension between them was thick: ‘Is that your perfume?’ ‘I don’t wear perfume.’ ‘Hmmm… you should.’

Their stressful day followed by a heavy night of post-work-drinks performance was part Jennifer Saunders and Joanna Lumley in ‘Absolutely Fabulous’, part Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani in ‘Possession’. When I was watching them pace in agitation into, through and back out of this room or that, fidgeting, wheeling around one another, setting about inessential tasks in a rage of feigned indifference, I was reminded that ‘Possession’, with its famously restless cinematography, was also a film of architectural, domestic and urban paranoia. Furthermore it witnessed a watchful, burgeoning middle class taste in pre-unification Berlin when many of it’s now chic streets were still dilapidated and menacing. Perhaps all parties are suburban revanchists, as per Neil Smith’s theory of the vengeful bourgeoisie reclaiming territory lost to undesirables. London’s more conventional opportunities for reclamation – and for profit – are somewhat sewn up, though. New depths of ingenuity will need to be plumbed but those at a loss need only think outside the box and never hesitate to take their queue from the artists.