As a small child, like many small children, I was afraid of the dark and going to bed would involve a dilemma. To avoid going to sleep surrounded by pitch black (the fear, I think, had to do with not being able to distinguish visually between the state of having my eyes closed or open) I would have to leave my door ajar to let in some light from the hall. And yet, lying in bed, I couldn’t help focusing on the vertical gap between the edge of the door and its frame, mentally conjuring all the things that might be just out of sight – witches ready to slip through the slit as soon as my eyelids fell. The hallway light would also let dramatic shadows leap onto the wall above my bookcase: I remember soft toys turning into looming mutant Donnie Darko-esque forms. Or, on one occasion, waking up in the middle of the night to see a shiny foil helium balloon, left in my room by my dad returning home when I was already asleep, transformed into a towering human figure made doubly terrifying by its reflection in the mirror at the foot of my bed.

Like many children, I also used to like confined space and building dens: creating a prism out of a clothes horse and draping a blanket over the top, or clearing enough room in my wardrobe to climb in, close the door and hide out until the pleasure of privacy turned through lack of attention into an uneasy state of boredom. This second habit must have involved confronting fear of darkness: it was no lighter under the blanket than in the wardrobe. Maybe the dark just wasn’t scary when I’d created the conditions for it myself, when I’d been in control and could emerge into light again at will.

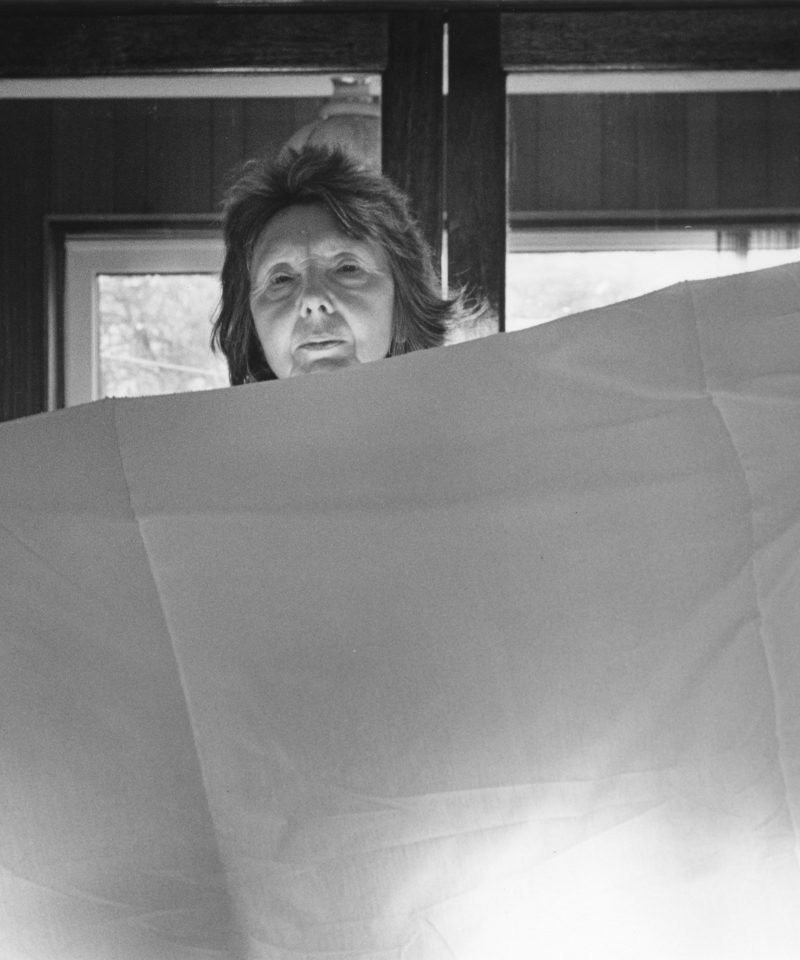

The distinction between personally controlled and externally imposed darkness is the only way I can think to reconcile the above two childhood experiences involving bedtime and play and fear and amusement respectively. It’s a distinction that I’ve been thinking about while looking at Tereza Zelenkova’s work, which appears, alongside the similarly black and white images comprising Matthew Finn’s Mother and Joanna Piotrowska’s studies of adolescent women, in the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2015 exhibition at Jerwood Visual Arts. Zelenkova’s The Unseen, 2015, depicts four women gathered around a lace covered table, three of them sat on wooden chairs, legs crossed and hands folded into their skirts while another stands behind the table in the background, ambiguously poised as either head of the family or a waitress preparing to serve. All of their faces have been covered in white fabric that hangs down around their shoulders and falls into points over their breasts. A wooden floor is visible but the background is completely black, making the group portrait the stuff of hallucinatory visions and haunting dreams, unnerving due to its lack of context and raising of questions we can’t as viewers hope to answer with any certainty.

Who covered these women’s faces? What kind of faces lie beneath? They look like they’re waiting for something – for what? Zelenkova places the viewer in a position of unknowing that I think of as resembling the position of the child who is afraid of the dark – I want to see and understand the things that an external hand has concealed. It’s like watching a horror film, when tension mounts around a figure, creature or force that is far scarier all the while it’s out of sight, often comical once revealed. In another photo, titled Dog Cemetery, Zelenkova allows the viewer to see everything within the frame, letting us feel more in control. And she also appeals to a playful tendency, learned in childhood, to look for faces in natural forms – a lump of rock set in one of the Czech landscapes of the photographer’s own childhood has well-defined eyes, nose and mouth.

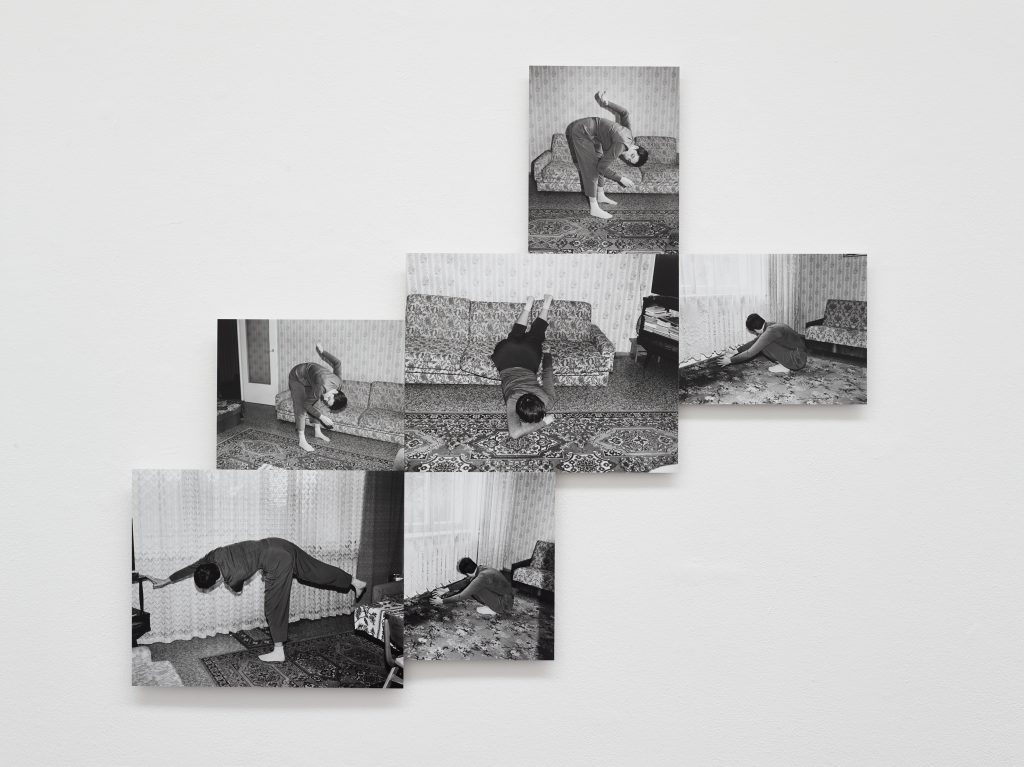

In Joanna Piotrowska’s work faces also take on an important role, and are for the most part either partially or completely hidden by body parts or hair, employed in the interests of self-protection or as a way of establishing privacy. We’re out of childhood and into adolescence in these photos in which the girls’ poses derive from self-defence manuals but sometimes look like they could instead originate from cinematic seduction scenes. The girl whose body is all angles, her jutting knee and elbow making lines as straight as those found in the hedge behind her and on the tiled ground, has become a shield ready to ward off anyone else.

But the girls sat on a wicker bench look as though they’re in a moment of indecision: caught between a headlock and an embrace.

Standing with her back to the pond, in a shot that makes me wonder whether Piotrowska has seen Stranger by the Lake, the girl with shadowy arms and long hair hiding her face could just as well be ready to pin down the friend she looks down on, or she may be contemplating a caress. I think to Berlin-based artist Anna Zett’s new video work Circuit Training and about Zett’s writing about self-defence, specifically boxing, which is described as ‘a radical form of dialogue, just like a caress, but at the other end of language.’ Boxing, like the work of Zelenkova and Piotrowsksa, also entails navigating the other and moving between positions of control or of being controlled. What I liked most about Piotrowska’s work is that the idea of transition and movement – along a scale of being dominated or dominating – is made physical: this exhibition represents the first time Piotrowska has used free-standing, larger than human size frames for the display of some of her work, which viewers have to encounter at different angles, do battle with or confront in some sense, in order to see the rest of the smaller, wall-mounted work.

These smaller pictures have been arranged so as to refer to spreads of illustrations laid out in self-defence manuals, however they refuse the instructional role that images in manuals usually aim for. Where figures in books would more commonly be photographed in spare settings, helping readers concentrate on the body, Piotrowska surrounds her subjects in busily patterned domestic environments where lace curtains clash with several different flower patterns embellishing wallpaper, carpet and couch. The comparative simplicity, clean lines of the girl’s body and the fact that she is acting out self-defence training methods, suggests the home itself is hostile and a context that the adolescent must learn to confront and distinguish herself against.