“The division of art forms into a hierarchal classification of arts and crafts is usually ascribed to factors of class within the economic and social system, separating artist from artisan. The fine arts – painting and sculpture – are considered the proper sphere of the privileged classes while craft or the applied arts – like furniture-making or silver-smithery – are associated with the working class … The development of the an ideology of femininity coincided historically with the emergence of a clearly defined separation of art and craft … the split between art and craft was reflected in the changes in art education from craft-based workshops to academies at precisely the time – the eighteenth century – when an ideology of femininity as natural to women was evolving.”

Rozsika Parker, ‘The Creation of Femininity,’ in The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, The Women’s Press, London, 1984, p 5

Katie Schwab’s artistic practice considers the collective nature and politics of craft, design and gender. Her mixed-media installation, as part of the Jerwood Solo Presentations (27 July – 28 August 2016), pays homage to the work of the block printers and textile artists, Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher. During the inter-war period Barron and Larcher, who were commissioned by a range of esteemed clients, including Coco Chanel, Girton College, Cambridge, the Duke of Westminster, and Winchester Cathedral, created a unique range of hand-block printed and naturally dyed textiles. Inspired by their prints, specifically ‘French Stripe’ and ‘Lines’, and as a way to explore techniques of pattern, abstraction and repetition, Schwab has created a large woodblock printed curtain (Lines) and three sets of striped wooden tables and stools (Stripes). The curtain, comprised of cotton dustsheets, was printed using foot pressure, a technique employed by Barron and Larcher’s contemporaries, the Footprints workshop. The third work, a 16mm video recording of the all-women Deep Throat Choir rehearsing, has been artfully hand-scratched. While the women practice Billie Holiday’s ‘Easy Living’, the camera sweeps the room, focusing on hands, tapping feet, and picking up on both overt and subtle patterns in everyday life. Shots of striped trousers; rows of trainer soles; bright socks; the curling of technical wires are punctured by Schwab’s visceral scratched lines, or flashes of opaque red. The title of the video, Covers, evokes both the content of the video and the commission as a whole. Schwab and Deep Throat Choir are traversing similar terrain by both ‘covering’ an artist – either through song, textile patterns or printing techniques.

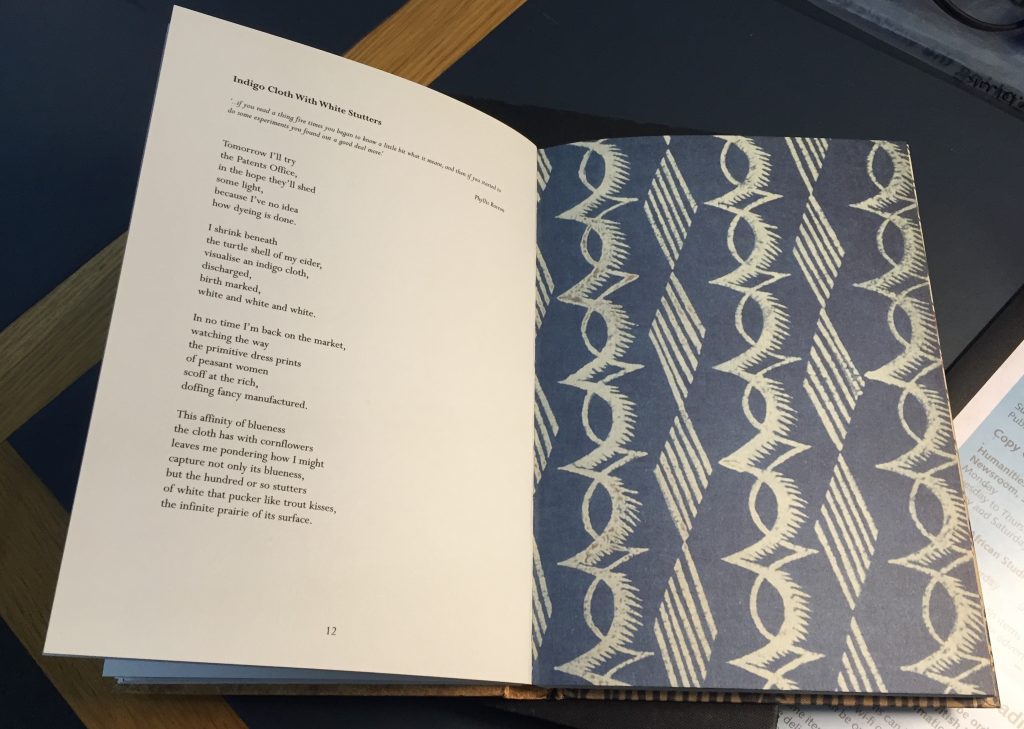

Jane Weir’s foreword to Walking the Block (2008), her poetic biography based on the lives of Barron and Larcher, evokes a similar sentiment, except Weir is using the written word as a means to create a generational dialogue between female artists then and now. The book layout creates a frisson between past and present; the design emulates the creative approaches of both women. Each poetic verse sits in adjacent to the different patterns, quotes or biographic details that particularly inspired its content.

“It was the language of the patterned textiles of Barron and Larcher that drew me to the making of the poems that inhabit this book; the unique rhythms, rhymes, repeats and the conversations running through their printed stuffs. Each length of cloth, which they named like a person or a particular place, sometimes the very spirit and essence of a place appears to take on a personality, which in turn seems to posses a distinct voice, speaking in its own tone, expressing it owns mood with its own inflections … And where one pattern is bold and abstract you are just as likely to find another that is quiet or contemplative, like a psalm or hymn flushed with subtle cadences … It is interesting seeing their patterns printed on different kinds of cloth, how the dialogues or monologues alter depending on the context; silk brocade, crepe de chine, linen, cotton, or velvet …. They used found objects, such as car mats, kitchen utensils, mollusc shells, cotton reels and seed heads, conjuring a kind of magic out of the ordinary and by doing transformed the nature of shape and line and contour with colour.”[1]

Although textile design is often signified within the female domain, women didn’t become involved with the field until the 1920s and 1930s. Before the First World War it was hard for women to train in craft or design areas, as these were traditionally associated with men. However, by the end of the war, women had sufficiently infiltrated the world of design enough to be able to take an equal place. The majority of women who were designing textiles in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s tended to have some initial art training, usually in fine art. They gained access to workshops, schools, professional training and, most importantly, were gradually allowed by the social conventions of the day to put their domestic skills – ‘a woman’s touch about the home’ – to commercial use.[2] There were also a number of important outlets for designers wanting to sell high quality craftwork and women ran many of these. Dorothy Hutton opened the Three Shields Gallery in Kensington in the early 1920s, the Little Gallery near Sloane Square, founded by Muriel Rose and Peggy Turnbull, opened in 1926 and Elspeth Ann Little ran Modern Textiles.[3] In the inter-war years the ratio of male to female designers became roughly equal. This was a situation distinct to the textile industry. Other areas, such as furniture design, commercial art, architecture, industrial design, ceramics and glass remained the province of male designers, while ‘less serious’ activities such as embroidery, were dominated by women.[4] Contrary to the stereotypical image of women’s craft as the passive woman with her embroidery frame, textiles often involved hard labour and perilous experiments; “it was women who adapted the skills of the hand-loom weaver to industrial production; who rediscovered formerly disregarded techniques of dyeing and printing; who re-interpreted Cubism and other forms of abstraction for use in the home and in fashion design; who, for the first time, went outside European culture to find patterns and colour combinations; and who remained true to their theoretical ideals while bringing colour and pattern into line with modern architecture”.[5] Phyllis Barron is a significant example of a woman who doesn’t fit the mould of a ‘soft’ female designer. She was often involved in hard physical labour and has written about perilous experiments with overflowing vats of boiling urine and barrels of indigo which set fire to her workshop as she attempted to master the art.[6]

During the 1910s artist printmaking in Britain had been revitalised by an upsurge of activity in wood engraving. This, in turn, fostered a revival in block-printed textiles, as some artists were inspired to move from printmaking on paper to printing on cloth. In block printing, patterns are cut in relief on wooden blocks (sometimes lino-faced), with multi-coloured designs broken into individual elements, each requiring a separate block. Hand block-printing had long been superseded by mechanical copper roller printing in commercial textiles and by machine surface printing in wallpapers – both of which were much faster and more economical for long production runs – although it was still used by a few specialist printers. However, the crucial difference between factory-made and craft-produced block-printed textiles was the artist’s direct involvement in the cutting of the blocks. Although labour intensive, block printing appealed to artists because of the control it gave them over the form, texture, and colour of the print. It also allowed flexibility as the same blocks could be rotated to create diverse patterns, and different blocks could be alternated to create varied effects. Two female designers, Elspeth Little and Gwen Pike, established London’s Footprints workshop, one of the most successful block-printing enterprises, in 1925 with funding from Celandine Kennington. Footprints displayed a lively, spirited approach to pattern. From 1927, Joyce Clissold emerged as chief designer, and in 1929 she took over as owner-manager and created all designs. Under her leadership Footprints grew into a substantial enterprise during the 1930s, continuing in operation until 1982, although latterly on a much-reduced scale. The firm produced finished goods such as scarves and ties, as well as dress and furnishing fabrics.[7]

In the introduction to A Woman’s Touch: Women in Design from 1860 to the Present Day (1984), Isabelle Anscombe suggests that “women [were] traditionally associated with nature rather than culture, a division which, in design terms, has placed in them in fields where manual dexterity, a feel for texture, a familiarity with natural materials – such as clay or vegetable dyes – and small, home-based workshops take precedence over man-made materials, large-scale machine production or an eye for three dimensional form.”[8] This is a fitting description of Barron and Larcher who had close contact with raw fibres, handmade textiles and pioneered the reintroduction of natural dyestuffs into fine art and design. This affinity with vegetable dyeing was marvelled at by Bloomsbury Group painter and critic Roger Fry in his 1926 Vogue on the pair, commenting that “something of the native grain survives in these stuffs … some vital quality that has not be pressed and stamped and tortured”.[9] Phyllis Barron first became interested in block printing on holiday in France when she was fifteen; a friend had bought some old French blocks as curio. While studying at the Slade, she visited the Patent Office to discover the ingredients of the necessary dyes and unearthed eighteenth and nineteenth century books that described the production of hand-block-printed textiles in India. Dorothy Larcher also trained as an artist at the Hornsey School of Art. In 1914, she accompanied a visit to India to record the frescoes in the Ajanta Caves. Unable to find transport home during the First World War, she remained in Calcutta, living with an Indian family and teaching English. It was during these years that she learned about Indian dyeing and printing techniques.[10]

Drawing on their knowledge of traditional French and Indian block-printed textiles, the two women developed a relaxed, personal style featuring a variety of abstract, organic and pictorial motifs. Although they fashioned their own individual design vocabularies, they worked closely together and evolved a coherent workshop style. Having distanced themselves from both commercial industry and the contemporary art world, they repositioned themselves within a global textile tradition, freely embracing elements of European, Asian and African vernacular design. Many of their patterns were geometric, although blocks, stripes or diamonds were frequently softened with crimped or serrated borders. Cloths varied in weight and thickness, depending on their intended application, and ranged from coarse linen and cotton furnishing fabrics to fine silk and velvet dress fabrics. Patterns were normally printed in a single colour. Discharge printing was also adopted, using nitric acid on pre-dyed fabric to bleach the cloth from dark to light. Initially Barron and Larcher favoured dark, earthy tones such as indigo and ironmould, but later they supplemented these with brighter colours, including quercitron yellow and alizarin red. After relocating from London to Gloucestershire in 1930, they continued to work together until 1939, but wound down their operations after the outbreak of the Second World War.[11]

Textiles signify a sense of multiplicity, either through the relationships between the specific individuals or communities who create them, or by the actual physical components of the making process and/or final object. It is also appropriate then that Schwab has included a video of a choir in her homage to Barron and Larcher’s textiles. The Deep Throat Choir are committed to exploring the ways in which song can explore the power of the collective voice. Similarly, Barron and Larcher’s successful partnership – the merging of two sets of well-suited skills and ideas – resulted in a unique and highly regarded creative practice. Schwab’s artistic evocation of cacophony and polyphony will be brought to life on 26 August when the choir will perform a live set of covers within the installation. I’m looking forward to seeing the result.

[1] Jane Weir, ‘Foreword,’ in Walking the Block, Templar Poetry, 2008

[2] Isabelle Anscombe, ‘Introduction,’ in A Woman’s Touch: Women in Design from 1860 to the Present Day, Virago Press, 1984, pp 11-15

[3] Boydell, op cit

[4] Boydell, op cit

[5] Anscombe, ‘Introduction,’ op cit

[6] Isabelle Anscombe, ‘The Simple Life,’ in A Woman’s Touch: Women in Design from 1860 to the Present Day, Virago Press, 1984, pp 155

[7] Jackson, op cit

[8] Anscombe, ‘Introduction,’ op cit

[9] Weir, op cit

[10] Anscombe, ‘The Simple Life,’ op cit

[11] Jackson, op cit