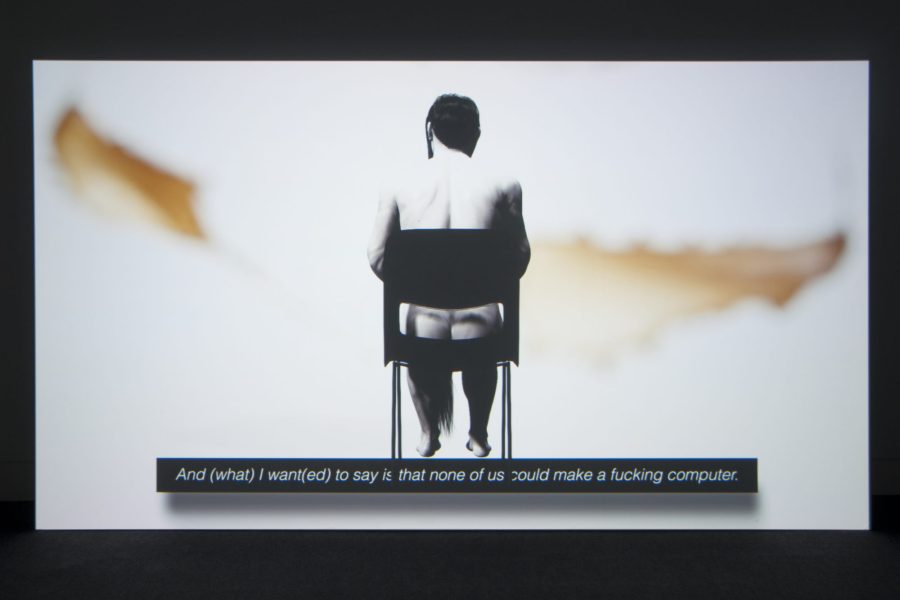

On Tuesday night, the Institute of Contemporary Arts screened a selection of Ed Atkins’ recent work, which was followed by a reading from the artist and a conversation with Steven Bode, the Director of Film & Video Umbrella. Almost every seat was taken in the ICA’s theatre and at 7pm the animated din subsided, the house lights lingered on for an awkward moment and then the audience was plunged into another world. Each work followed on directly from the last, culminating in Material Witness OR a Liquid Cop (2011) and then its sequel Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013).

The experience was intense, especially when sat on the second row, with the looming screen and booming sound demanding a visceral response. Watching the work in this way (without a palate cleanser between courses) felt a little queasy and the evening, in the words of one of Atkins’ lines, might be ‘remembered in fragments with surf-rounded edges’. A legato stream of images scintillating with meaning; a CG-man with soft-kohled eyes and an impossible number of teeth; a muffled cough, a click, a clap; the sense of traversing epic distances; a neon frog leaping in and out of view; endless filters; a melancholic voiceover; ‘and all that fucking hair’.

Afterwards, Atkins read from the extended script that accompanies Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths and I thought again about the Gilbert Sorrentino poem, The Morning Round Up (1971), that he cites:

I don’t want to hear any news on the radio

About the weather on the weekend. Talk about that.

Once upon a time

A couple of people were alive

Who were friends of mine.

The weathers, the weathers they lived in!

Christ, the sun on those Saturdays.

Situated in the context of Atkins’ HD video, the mere mention of radio seems to ache with nostalgia for an analogue era – perhaps particularly given the recent debates around DAB. I was reminded of a brilliant passage of Leo Steinberg’s writing, first published in Artforum in 1972 (a year after Sorrentino’s poem), in which he talks about the permeability of Rauschenberg’s picture plane:

‘I once heard Jasper Johns say that Rauschenberg was the man who in this century had invented the most since Picasso. What he invented above all was, I think, a pictorial surface that let the world in again. Not the world of the Renaissance man who looked for his weather clues out of the window; but the world of men who turn knobs to hear a taped message, ‘precipitation probably ten percent tonight,’ electronically transmitted from some windowless booth. Rauschenberg’s picture plane is for the consciousness immersed in the brain of the city.’ [1]

I wonder if something similar might be said of Ed Atkins one day: that his videos are for the consciousness borne out of the digital domain.

The ensuing conversation with Steven Bode suggested that Atkins’ concern is very much with the present rather than posterity. Bode began by reminding Atkins of their early email exchanges about Dennis Potter and the techno-utopian promise of virtual reality – ‘it strikes me that what you are doing is quite the opposite’ said Bode, ‘that you are… illuminating the meat’.

It was interesting to hear Atkins respond about the increasingly immersive, ‘corporeal address’ of mainstream cinema and the effect that his work, by contrast, might have on the viewer. ‘You can be perpetually spun back and forth’, he explained, ‘rather than the movement being in one direction. So the work maybe will pull you in, and pulling you in might be an act of leaving the body, but then you’re returned to it, and you cover vast distances, and you may go to another planet or the bottom of the sea, and then you’re back in your seat, or you’re inside your mouth and then you’re feeling aroused or you’re feeling desperate…’

Atkins’ flow suggests that the viewer might become sensitized to the subtle shifts the work enacts on them, both emotionally and physically, suspending them in a perpetual present, much as he wishes the work to be. ‘I don’t believe in any of the immortal things about technology… the possibility of the immaterial, it’s a great fantasy, it’s totally rich… but I don’t want to live forever and I certainly don’t want the work to and maybe there’s an interest there – or a complete disinterest – in the maintenance and the future of the work. It’s very much a wanting to apprehend something now, to feel it now, to be with it in the moment… to delineate a present’.

The title of the exhibition at the Jerwood Space, Tomorrow Never Knows, seems to suggest an ellipsis… and hearing Ed Atkins talk about his work, I wondered whether the final word might be ‘today’: Tomorrow Never Knows… Today.

[1] Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: The Flatbed Picture Plan, from a lecture delivered at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, 1968; first published in Reflections On the State of Criticism in Artforum, March 1972