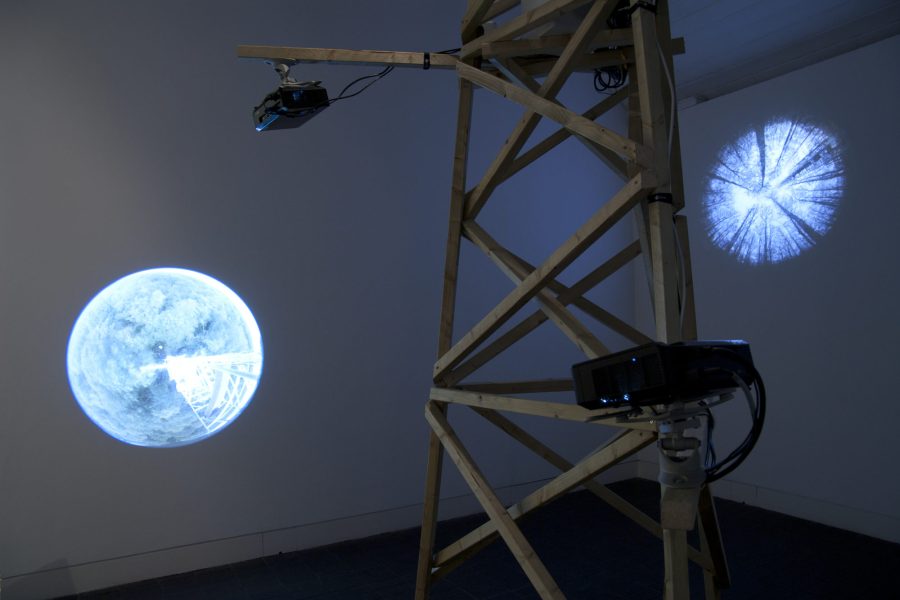

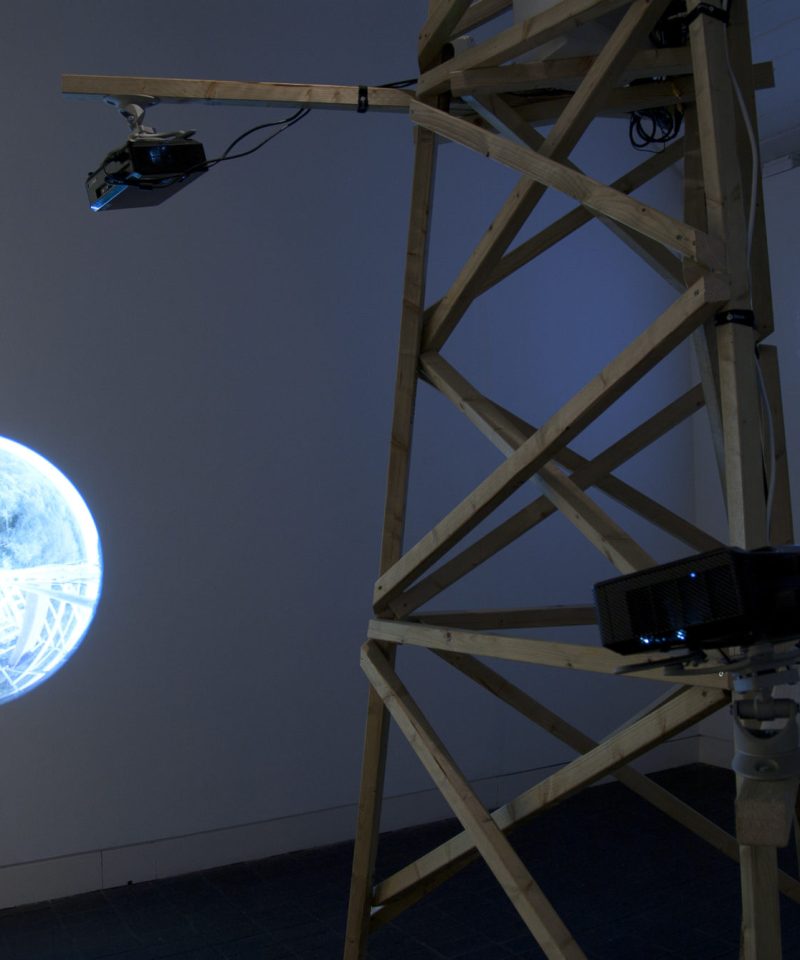

Within Jerwood Visual Arts there are five proposals. From sawmills to ravens, to the tinnitus ringing in your ears amid a dense silence, each artist selected for the Open Forest has developed a unique proposal, the bones of a commission that could later exist somewhere in Britain’s forests. Using video, ambisonics, live performance and data drawings, the artists have created protean forms – suggestions of what might be to come. The commission is unique in that it straddles two very different environments, and in doing so raises questions about the places in which contemporary visual arts practice operate.

In the 1960s the term ‘Land art’ emerged, signalling a practice that existed outside the gallery walls. At that time, in the pages of Artforum and The New York Times, critics and artists alike spoke of their disillusionment of the commercialisation and insularity of the gallery. Ecological and environmental concerns activated a new anxiety and call for a new kind of outside engagement. In 1967, the then 22-year-old Saint Martin’s student Richard Long walked across a field back and forth, marking a track in his wake. The piece, A Line Made by Walking (1967) now seems to characterise the fine-drawn, romantic nature of much of the Land art that followed, a movement that often produced ephemeral works which could instantly disappear, engulfed or washed away, operating in a grey area between performance, installation and sculpture. Similarly, David Tremlett’s piece The Spring Recordings (1972) captured a snippet of sound from each of the 81 counties that make up England, Scotland and Wales. A close-listening on a huge scale.

In the catalogue for the 2013-2014 touring exhibition Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1966-1979 , the curators Joy Sleeman, Nicholas Alfrey and Ben Tufnell write that Harald Szeemann’s 1969 exhibition When Attitudes Become Form arguably encapsulated a significant moment in contemporary art, but that the show’s subtitle – Works, Concepts, Processes, Situations, Information – indicates a set of concerns shared by the artists who were moving their work out into the open. In this sense, Land art did not, and perhaps still does not, differ conceptually from work produced within the urban, gallery context, but rather it is characterised by an attitude to the outside world.

In the Jerwood Open Forest exhibition, it occurred to me that this might be a Land art 2.0 (forgive me the cliched term…), less concerned with large-scale material propositions, but perhaps evidence of a new attitude which incorporates the technological and visual forms of mediation through which we now encounter the outside world. In January 2014, I spoke with Hayley Skipper, the Forestry Commission’s art curator, who spends most of her time travelling between forests engaging in projects with artists, locals and visitors. We spoke about some of the ideas around the project, and what it means to present an artwork both in an urban setting, and in the deepest darkest forests…

It struck me that what appears in the gallery has some relationship with Land art , but that the works build on and expand that artistic history, and are moving elsewhere…

I think the fact that we are only offering a £30,000 commission does have some sway in this. Not that you can’t produce a piece of Land art for that amount, but I think that does affect the sense of scale. For the final five selected for the Jerwood Open Forest, we wanted this to be a more public work than perhaps they would normally produce. It wasn’t a deliberate – we didn’t decide to ‘take the digital outdoors’ – but we haven’t been afraid to embrace new technologies. It’s actually quite a tech-heavy show. I think that does say something about where art practice is at. The artists are all in differing ways attempting to capture the immateriality of the forest, too. That seems to be thematic; that sense of something happening in a moment, of performance, of temporality – and how possible it is to capture things through film and visual documentation. All the artists have been thinking about the legacy of the work too, so in that way too it has brought in the history of Land art and how it does often live on through film, rather than through a primary experience of being there.

The artists don’t seem necessarily to be interested in ‘installing’ something into a place, but exploring how they might be able to change the atmosphere, or change the sensation of being in the forest.

Even with work that isn’t sculptural or land-based, well, anything at all in our culture now, not just visual art practice, it’s mostly all now mediated by devices, digital technology, visual media… We were trying to acknowledge the different spheres in which works sit, and travel. But of course, we are also conscious of our audience. We are thinking about how this commission sits within the various geographies across Britain, but it also wasn’t entirely about people going out into the forests, but also bringing the forest into the contemporary art milieu.

Is there still a political dimension, in general, in the act of artists and artworks moving outside of the gallery? I’m thinking of the way the 1960s Land art movement was characterised as ‘in opposition’ to something.

In many ways it’s a recognition of the artists who are operating outside the gallery, but also an encouragement to those who are – it’s a provocation in some way. Critical practice can happen anywhere, it’s just a case of broadening our understanding of ‘anywhere’. Part of the reason we have included the exhibition in the Open Forest format, is because we didn’t want to set it up as an exclusive thing centred around a rejection of the gallery. We wanted to operate in both those languages.

Is this a process you have worked with before?

I trained in Fine Art at Wimbledon in London, and then went on to study sculpture, so I suppose I’ve arrived at curating from a practitioners perspective. I used to work a lot in the outdoors, and I also ran projects with students which were all about taking the institutional capital of the university and transplanting that into the community, or into a wider environment. I’m primarily interested in that intersection. Like now, for example, I’m working with the fact that the Forestry Commission isn’t an arts organisation, but I’m exploring the exchange between the non-art institution and artists, and what they do, and how audiences experience that. That’s the theme that runs through everything I do. As a practitioner, it was precisely the negotiation part which interested me. I worked a lot collaboratively, and that very broadly is key to my role now, and to this project here.

A typical interviewer’s question, but I’ll ask it anyway: was there an artwork which first inspired you to work in this way?

The moment that immediately springs to mind is when I first saw the Turner Prize on TV. At that point, I didn’t really know what it what was, but Rachael Whiteread had just finished her Artangel commission, House (1993). It just seemed to be to be such a radical thing to do; to make sculpture in that way, so completely rooted in its context, and yet still a formal sculptural proposition but which couldn’t be separated from its landscape and its context – and its time. I think that was definitely a moment when I realised, wow, art can do that. Art can stand alone and make a statement, for itself, about a time and a place. That was definitely a landmark. It still feels exciting, even thinking about it now.

Hugo Young, The Guardian, 25 November 1993:

“In the East End of London, Rachel Whiteread’s architectural sculpture, House, has been voted into destruction. House is a modern masterpiece. In it an ingenious idea is realised with great evocative power. Taking a derelict dwelling, Whiteread has turned it inside out by casting the interior in liquid concrete then removing the bricks. What is left is a monument to past domesticity, a coarse yet intricate edifice, alone in the space it once occupied with a hundred similar residences. It satisfies contemplative as well as aesthetic taste. Once seen, it makes you look at all houses in a new way.”

Since that time, do you feel that because we engage with culture through new and changing digital means, this has meant that we engage with outside spaces less, or differently? In your role for the last six years, have you noticed a difference?

I’m not sure. I think there is definitely something different in how we experience landscapes and the outdoors, and our notions of the outdoors, which is mediated through our cultural and technological consumption. On one level, I think that excellent television programming, cinema, digital projects which allow us a certain access to the environment when we are unable to explore them first hand actually expand our horizons. But there is also another dimension, which is on a more pragmatic level. I see many people arrive at the forests bewildered because their sat-nav doesn’t work, and they have no phone signal. They can’t ‘plug in’. But it may also be a big part of why people come at all, because they don’t want to spend an afternoon on the Internet.

—

You can read more about Forest Art Works, and other Forestry Commission projects here.