The Singular

Hysteria is understood through the body; physical symptoms stand in for a disorder that cannot be located in the body, but can only articulate itself by proxy in a corporeal register. It is an illness which blindly calls for documentation, representation and reenactment. For the singular, hysterical body, drawing was an analytical means of distilling these physical manifestations, crystallising states and stages of mania into expression or gesture: ‘Melancholy passing into Mania’, ‘ Religious Mania’, ‘Head of an insane woman’.

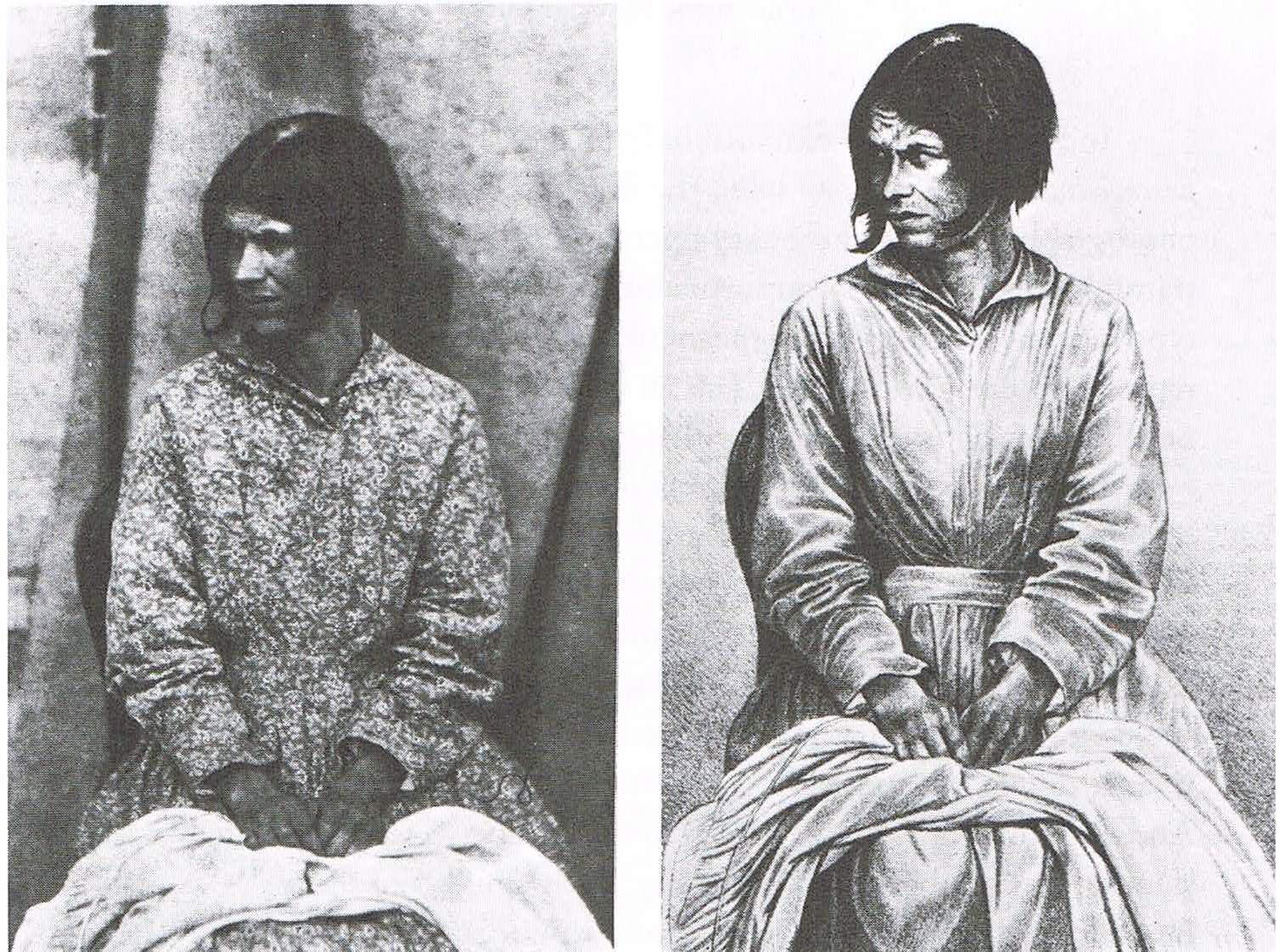

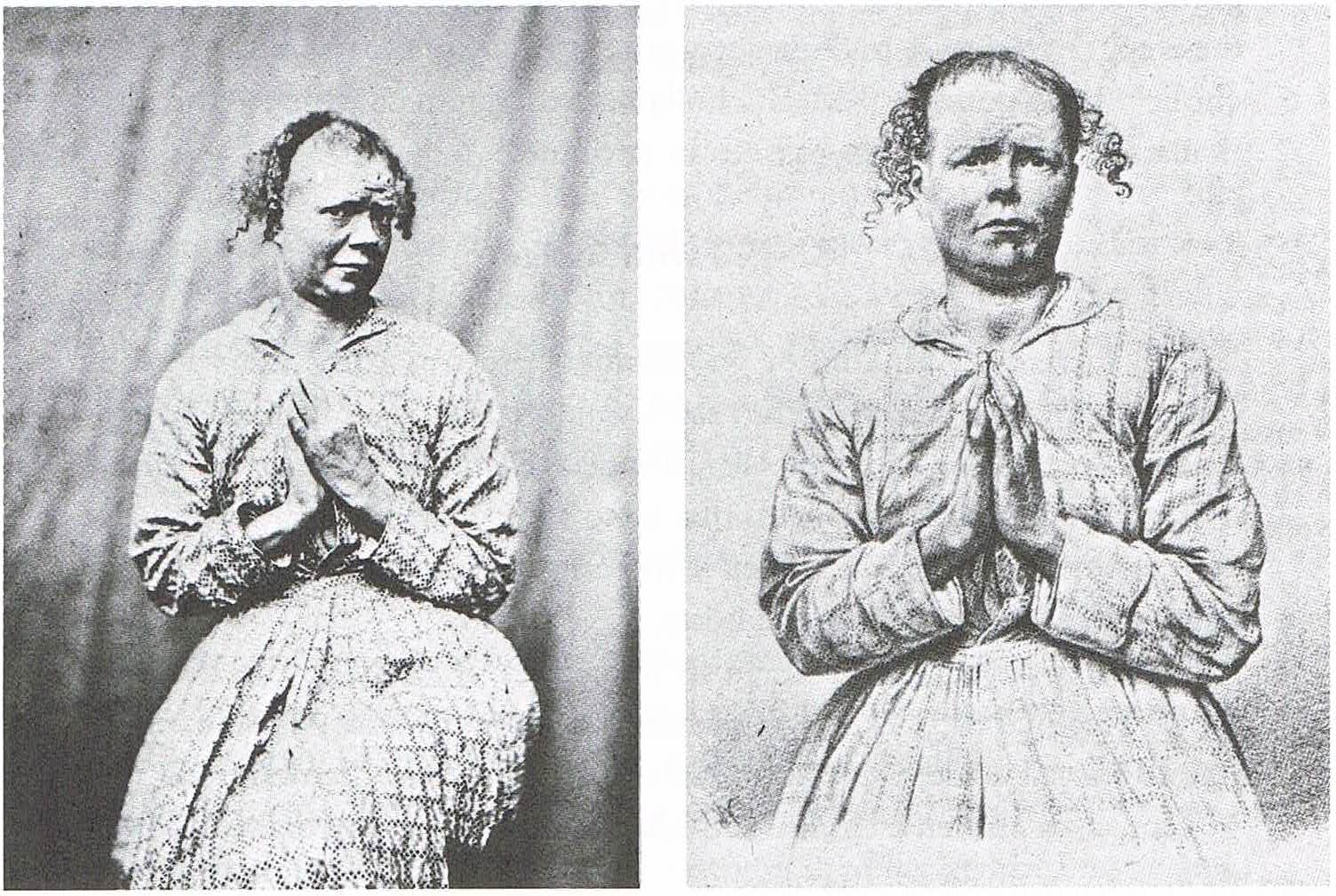

The relationship between drawing and hysteria is inextricably linked to its progression into photography. Drawn images of patients preceded the incorporation of the photographic medium into medical practice, and then set out to respond to it. In the early 1850s it was still necessary to go through the lengthy process of producing a line engraving copy of a preparatory drawing, which itself was based on a photograph, in order for the images to be reproduced and disseminated. This practice augments the distanced relationship between subject and image, resulting in codified, ‘signifiers’ of madness. It evades a direct relationship between madness and drawing, producing a tension between repetition and representation – of formulating repeated identifications.

When seen next to their photographic counterparts, these drawn images demonstrate an erosion of specificity. In the photograph version of ‘Melancholy passing into Mania’, there is a (vague) suggestion of location – the subject exists, at least, in relation to her surroundings. In the engraving, this has been removed, rendering her gaze irrevocably insane, independent of space or destination. Similarly, in ‘Religious Mania’, the hands of the woman, along with her gaze are seemingly unconvinced of their ‘religiousness’. The engraved image straightens the hands, eradicating any ambiguity of their intention, so she clearly becomes a woman suffering from ‘religious madness’. She is, in fact, an alcoholic. These images do not attempt to illuminate an attribute of the referent, i.e. ‘melancholic’ or ‘manic’, but instead represent a concept, i.e. ‘melancholy’ or ‘mania’, the referent reduced to mere attribute[9]

The photographic publication The Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière contains within it every conceivable pose of prescribed hysteria: attacks, cries, ecstasy, ‘attitude passionelles’ (an obsolete term for a position suggestive of orgasm), ‘epileptoid phases’, delirium, ‘crucifixions’. The desire for photographs of hysterical women necessarily influenced the illness itself and its symptoms; it emerged as a strategy of self-fashioning and theatre, as repetition reduced its subjects to object and image. Photography, in extension of drawing and printing, was the ideal process to crystallise the link between the fantasy of hysteria and the fantasy of knowledge.

The female hysterical body is pure signifier. The photographic and drawn image, which here are almost exclusively inextricable from one another, further establish the presentation of madness as female. The ‘hysteric’, like a mummy or a puppet, becomes seized by affective meaning, of message converted into the body; it becomes a vessel, nothing but the place of representation.

The Collective

If my mouth came out of your mouth

and my teeth were born into your teeth

we would be sisters

we would be so closely related

we might even be twins

twins who tumble their limbs together

and bend so far backwards

we become snails

There is always a gap.

While conversion disorder is the physical manifestation of mental trauma or psychosis, there is inevitably a gap within the translation from one system (mental) into another (bodily.) There will always be that which is incommunicable. The analytic image does not account for this gap. Instead, it aims to make visible what is already visible – to represent what is seen as the articulation of the mental via the body.

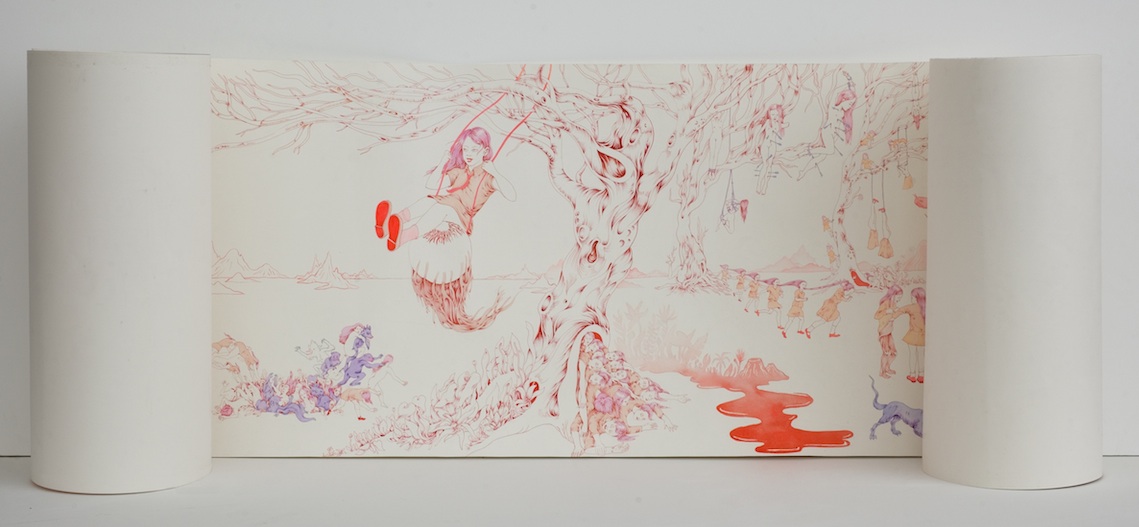

In her drawing Unsolemn Rituals, Amélie Barnathan uses the medium as a tool for representing the unseen, transitory nature of psychosis. Her expansive fabrication of MPI centres around hundreds of girls, struggling with each other, struggling with beasts, converging together, naked, dressed in uniform, victimised and victimising one another. Her work, nearly 5 meters in length, parallels the fluctuating, unstable nature of drawing with the act of collective unravelling, as psychogenic illness spreads through a community of ‘susceptible’ female youth.

A string of girls run, their hair emanating out of the mouth of the preceding girl, so they fall out of each other, seemingly choking each other into existence. A hoard of unconscious girls spill out from the bowel of a tree, their arms and hair resembling roots. Girls laughingly lift up their skirts and their skin, revealing muscle and clawed feet. They hang from and scale trees, some levitating out into the distance, others usurped by their own clothing. They impale each other and dance together, crucify a heavily pregnant girl and watch another as she contorts on the ground, snakes protruding from her eye sockets.

Drawing, in comparison to painting, is an unloaded medium which evades the weight of its own history. It is perpetually open, re-visitable and on the verge of being eliminated. Barnathan’s fantastical environment relies on this transformative and generative tool. Figures merge into roots, snakes, leaves, hair and other girls, their figurative boundaries precarious and permeable. Their drawn presence is as volatile as their collective psychosis. As the girls revel, enraptured and emboldened by their ‘illness’, the image of the Victorian female malady is displaced. Responding to and assessing themselves in relation to one another, their madness is independent of a historical, male system of diagnosis. The ecstasy is ritualistic, their sexuality is unashamed and unaffected. These girls have established their own order, it might be violent but it is their own.

MPI is a form of genesis – people can become afflicted without any prior mental illnesses, and can return to their preceding mental state after the episode has passed. It is a temporary condition which (not) simply requires the awareness of the ‘sufferer’ to overcome it. The ‘sufferer’ is literally drawn into the suggestion of their own illness. Their behaviour joins a joint, bodily vocabulary. As an ‘anti-medium’, drawing corresponds to this dislocation, of being two things at once. It does what photography cannot do – it illuminates what is not communicated via the body and its indexical image. It twists and distorts new formations into existence and the amalgamation of entities creates an impenetrable collective action.

There is always a gap. But drawing is the closest you can come to filling it.

[9] Didi-Huberman, 39

Bibliography

Bartholomew, Robert, Mass Hysteria in Schools: A Worldwide History Since 1566, 2014, McFarland & Company Inc., Publishers

Chesler, Phyllis, Women and Madness, 1973, Avon Books

Cixous, Hélène, The Laugh of the Medusa, published in Signs, Vol. 1, No. 4. (Summer, 1976), pp. 875-893

Didi-Huberman, Georges, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, 2004, MIT Press

Dyer, George, Written in Bedlam: On Seeing A Young Beautiful Maniac, 1801

Showalter, Elaine, The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830-1980, 1987, Virago Press