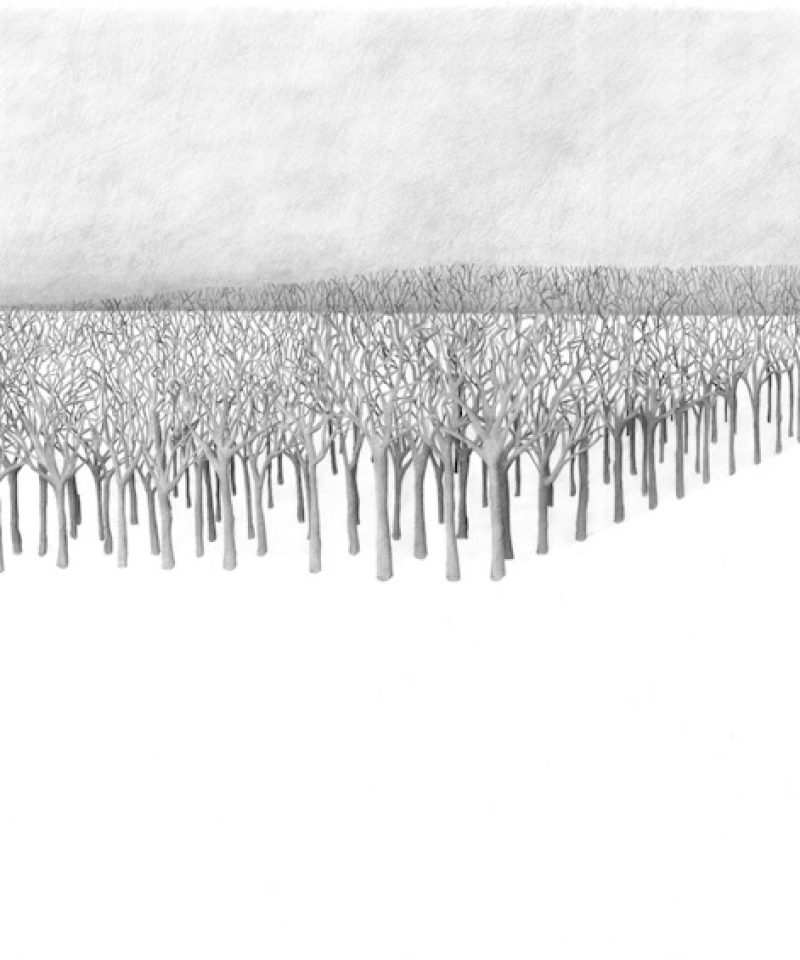

This is a two-part essay written in response to Amelie Barnathan’s drawing Unsolemn Rituals, which is currently on view as part of the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2016. Barnathan’s drawing investigates the phenomenon of mass psychogenic illness, often colloquially referred to as mass hysteria, which is the rapid spread of illness signs and symptoms within a cohesive group, where there is no organic cause. Episodes of MPI are surprisingly regular occurrences, with large scale examples affecting up to 1,000 people.

Part One investigates the ideological differences between these collective episodes of hysteria and its historical predecessor: the female ‘hysteric’ in the nineteenth-century and onwards. Part Two will continue this distinction, looking at the representations of women within these two interdependent, but fundamentally opposed, understandings of madness.

The Singular

‘The ethic of mental health is masculine in our culture’[1]

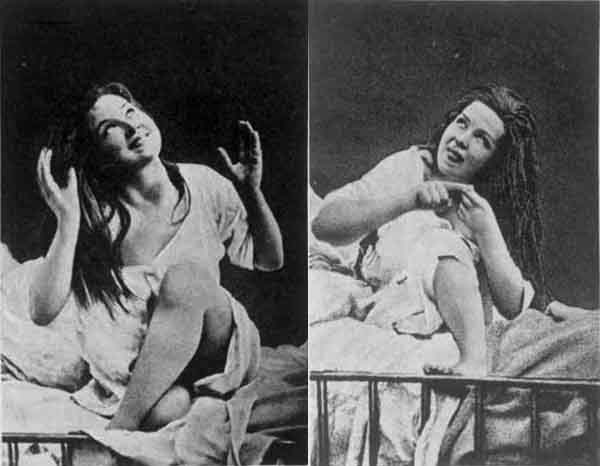

Hysteria is taught through the specificity of women. Despite its formless condition, it is historically defined by example. In 1875, 15-year old Louise Augustine Gleizes was admitted to the Salpêtrière women’s hospital in Paris. At the age of 13, she had been threatened with a razor and raped by her mother’s lover, and sexually attacked by other men in her neighbourhood. She arrived at the hospital with paralysis of sensation in her right arm, and pains in her lower right abdomen. Under the care of neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, Augustine spent five years half-exposed and photographed incessantly as an embodiment of hysterical ecstasy. In the winter of 1876, she had 154 fits in one day; she heard voices, saw swarms of black, and was in and out of consciousness, her body convulsing in a series of violent seizures. Augustine was the star of Charcot’s theatrics until 1880, when she disguised herself as a man and disappeared completely.

These examples, women with names but seemingly not much else – Augustine, Mary, Kate, Blanche – become mythologised through their introduction into a framework of madness, spectacle and diagnosis. Within this fundamentally male system their specificity becomes archetypal; Mary becomes ‘Mad Mary’, Kate becomes ‘Crazy Kate’, and Blanche, (paradoxically) among others, becomes the ‘Queen of Hysterics.’

For the ‘mad’, in nineteenth-century England there were two possibilities: the English malady, associated with the intellectual and economic pressures of highly civilised men (i.e. something external), or the female malady, which was associated with sexuality and the essential nature of women (i.e. something internal).[2] Even in mutual madness, when suffering the same symptoms, women were assessed and diagnosed in opposition to the white, male position. This position is not afforded a madness which is fundamentally male. Unlike the woman, the man was not hysterical. His madness not innate, but something independent of its subject, a consequence of his surroundings but not his sex.

In the first century of its existence, St Luke’s Hospital in London, received eleven thousand, one hundred and sixty-two inmates. Eight thousand, seven hundred and fifty-nine of those patients were women. The prevalence of women in asylums begs the question: were women more prone to hysteria, or simply more prone to a diagnosis of hysteria? The classification of hysteria as a female malady creates problems for its own examination: is hysteria associated with the female because there were clearly a large volume of female sufferers, or were more women diagnosed as ‘hysterics’ because of a prescribed correlation between hysteria and the female.

What is most prevalent is a fundamental alliance between ‘woman’ and a reductive notion of ‘madness’. Within our dualistic systems of language and representation, women are often situated on the side of irrationality, silence, nature and body, while men are situated on the side of reason, discourse, and intellect. From the late eighteenth century, there was a growing cultural tradition that represented “woman” as madness, and that re-appropriated images of the female body to personify the irrational and unpredictable. While the name of the ‘female’ disorder may change over the course of history, the gender imbalance of its representation remains the same. Madness, even when experienced by men, is metaphorically and symbolically represented as feminine.[3]

When madness is female, madness is beautiful. George Dyer’s 1801 poem Written in Bedlam: On Seeing A Young Beautiful Maniac, details a ‘sweet maid’ with a ‘gentle bosom’: ‘pity’s child, the friend of misery.’[4] A victim of her own gender, sexuality and feminine nature were viewed as the source of woman’s madness, her ‘gentle irrationality’ inevitably susceptible to perversion. Literary archetypes emerged as civilised interpretations of female insanity: the pious, suicidal Ophelia – naive but explicitly sexual; the sentimental Crazy Jane, who goes mad after being abandoned by her lover, and violent Lucy/Lucia, whose sexuality presents as violence against men. Women were understood through example; they were read in their relation to male sanity.

What was considered madness was either the acting out of the subordinate female role, or the rejection of one’s sex-role stereotype.[5] For Hélène Cixous, madness is the historical label applied to female protest and revolution. Cixous writes of the ‘admirable hysterics’ of the late nineteenth century as a feminist tool for champions of defiant womanhood.[6] But, hysteria is determined by woman’s relation to the man; its very diagnosis is dependent upon a framework of opposition. The singular, hysterical body necessarily loses any political power, or the potential to subvert the logic of male science, when it is subsumed into a system governed by male dominance.

The Collective

‘Woman for women – There always remains in woman that force which produces/is produced by the other – in particular, the other woman.’[7]

Hysteria is historical. By the early twentieth century it had disappeared from the medical realm, and was gradually replaced with a greater, and more fluid, understanding of psychological illness. It has persisted in popular culture, along with its associations with the ‘feminine’. Groups of girls who would shriek and faint at seeing Elvis Presley or the Beatles have been classed as hysterical – their hysteria produced in response to the men they admired, or desired. Applying the terminology of ‘mass hysteria’ to these hoards of girls perpetuates the Victorian understanding of the female hysterical body: to be so overcome by their own sexuality that it results in insanity, to become so aware of your own (inferior) sex when faced with its rational, distanced counterpart. To term this reaction as hysteria is an extension of the long medical tradition of considering madness as inherently female.

In the 1970s, in a London girls’ school a seventeen year old called Anne became pregnant, gave birth, and died shortly afterwards due to a burst blood vessel in her brain. Around this time, her best friend Louise began to suffer fainting spells, suddenly dropping to the ground in class; she would curl up on the floor and appear to sleep, and at times roll her eyes and flail uncontrollably. Soon after, Margaret began to faint, then Rosemary began to faint, until five more classmates and one teacher were afflicted. The class was sent home a week early for the Easter holidays, and Louise was admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where she announced she was pregnant. This mere (and false) suggestion of her own pregnancy instigated a panic amongst her fellow patients regarding their own potential pregnancies. Several began to complain of the same symptoms and, despite in at least one case having no sexual experience, required medical assurance that they were not carrying a child.

In cultural and social disciplines, this type of episode may still be referred to as mass hysteria. Medically, it is called mass psychogenic illness (MPI), and revolves around the principle of conversion disorder. Conversion disorder, a contemporary understanding of hysteria, is the manifestation of mental trauma as physical symptoms. MPI is the onset of these physical symptoms among a group of individuals, which are exhibited unconsciously with no corresponding organic cause. Common symptoms are headaches, dizziness, nausea, fainting, non-epileptic fits, hyperventilation and twitches. Historically, these outbreaks occur in strict, regimented communities or institutions, and well over 90% of affected individuals are female.[8]

Although MPI relies on individual psychogenic symptoms, it is dependent upon the relationship between individuals. While the singular ‘hysteric’ is assessed in relation to the male, episodes of MPI are instigated and unconsciously progressed by the female in relation to other females. Typically, in instances of MPI there is an instigator who has genuine symptoms of illness – physical and/or mental, whose condition induces the belief that their illness is a contagion. It spreads through close proximity; friendship and admiration is its biggest ally. In the episode with Louise and her fellow patients, Louise was described as popular and influential. In place of the male diagnostician, Louise becomes a quasi-ringleader, managing her own circus of women.

While the limitations placed upon the singular hysterical body disrupt any readings of the illness as a feminist agent, the notion of MPI suggests an affinity with subversive action. In her 2014 film The Falling Carol Morley presents a group of teenagers who become afflicted by an outbreak of fainting at an oppressive all girls’ school in the 1960s. After Lydia’s best friend Abbie dies suddenly from a frenetic, mysterious fit, Lydia begins fainting at school. This soon becomes an epidemic, with girls experiencing rapturous episodes before dropping to the floor like lead. The girls’ performance, whether conscious or unconscious, becomes an insurgent tool to challenge the authority of their teachers. Their other-worldly gestures, as though possessed, as they accumulate and burgeon, become a defiant, collective action.

MPI is a phenomenon concerning the power of suggestion. It is also a phenomenon which concerns the power of women in relation to other women. As the antithesis to solitary madness, to be mad en mass is to establish a new order. The proliferation of symptoms in relation to one another refuses the history of the spectacle of the female malady. It is a temporary state, which does not actually require or result in madness. It is a loss of history, but not necessarily future. It is unconscious, but it is not without decision.

[1] Chesler, 69

[2] Showalter, 7

[3] Showalter, 3

[4] Dyer, 1801

[5] Chesler, 56

[6] Cixous, 886

[7] Cixous, 881

[8] Bartholomew, 182