‘Sounds are affective. Images are instructive’. Lis Rhodes [1]

Tuesday night was the opening of Tomorrow Never Knows, the Jerwood/FVU Awards. A throng of visitors arrived at the Jerwood Space, eager to see the new commissions by Ed Atkins and Naheed Raza. Both artists were selected from a shortlist of four (whose pilot projects, including work by Emma Hart and Corin Sworn, were exhibited in Spring 2012) and given £20,000 to develop their ideas into finished works. This lent the occasion a certain thrill, particularly for those who were returning one year on from Tomorrow Never Knows: Part 1. There seemed to be the added intrigue of comparing an imagined outcome to its finished product along with the intimacy of seeing how nascent ideas had crystallized.

Standing amid the lively din of the crowd, I thought about the way in which we encounter moving image works in the context of a private view. The opening night of an exhibition stands in contrast to our traditional expectations of a gallery – in which silence is considered imperative for contemplation – or a cinema – in which a hush, at least, is seen to allow for the audience’s immersion in the action. In preparing an exhibition with film content, a great deal of time is spent anticipating problems such as ‘sound bleed’ (a term sufficiently violent to reflect the strength of this curatorial phobia), yet most concede that little can be done on the opening night to insulate the darkened room from the thrum of art world chatter outside.

But what if this setting were to amplify rather than compromise our experience?

At the Jerwood Space, Naheed Raza’s Frozen in Time (2013) is presented in the first of two near-identical blacked-out rooms. The work investigates the practice of cryopreservation – the rapid cooling and storage of the body or brain after death so that it might be resuscitated in a future age – with interviews intersected with long, elegiac shots of cryonics institutes across America. With her meticulous, clinical style (the product perhaps of an initial training in medicine) Raza allows a certain skepticism to undermine the increasingly far-fetched claims of her subjects. Watching the video play out in the warmth of a room crammed with other bodies I felt more aware of my somatic self. The sensation was shared by the artist Sonia Boyce, who ‘started to think about my own mortality and the inevitable mortality of everyone in the space’.[2]

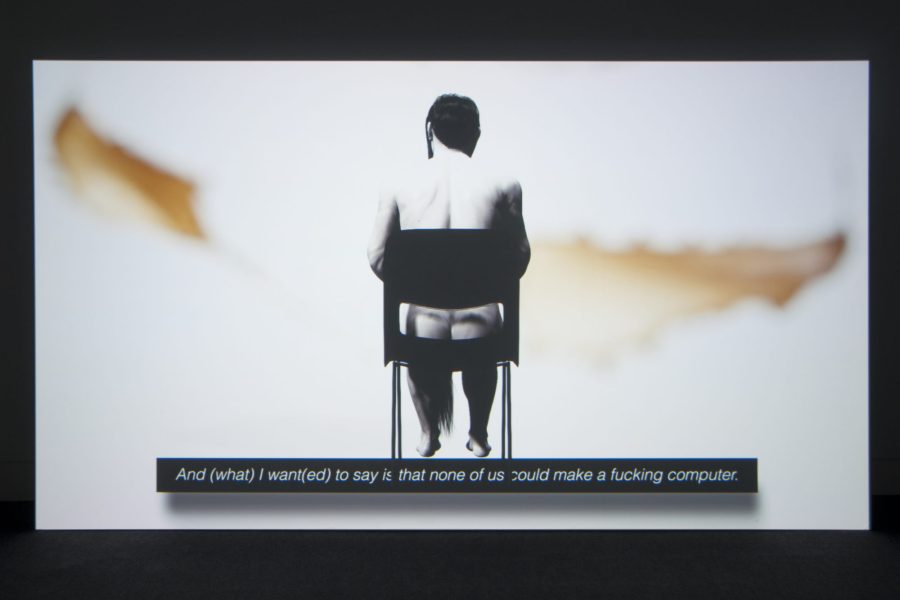

Installed in the second room is Ed Atkins’ Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), a high-definition video featuring an animated man, seemingly submerged in an ocean of water, speaking in fragments of phrases that feel as strange and familiar as the single white headphone plugged into one of his ears. The vivid blue feels meaningful as a colour: an allusion to chroma-key and the possibilities made real and realities made possible in the age of post-production. The digital-motion-capture techniques used by Atkins give the work a natural affinity to the computer, and watching it play out on this scale, with the pulse of a party in the air and a room full of half-lit faces, I felt all-too conscious of the atomizing perils of laptop life.

So both works seemed to find added resonance in the ambience of the private view. Instead of the empty, hallowed space of the white cube, in which the artwork looms large, or the blacked-out auditorium of the cinema, in which the audience can become subject-voyeurs, we encountered the two works in a busy, darkened gallery – a discursive space made more so by the sense of social occasion. In light, perhaps, of the recent programming at Tate Tanks, I was reminded of the event-based practices of the London Filmmakers Co-op and an artist like Lis Rhodes, who has always encouraged an activated audience. As Lisa Le Feuvre writes Lis Rhodes films rely on the viewer’s enagagement. The film is not the only thing at work: the viewer’s own interaction and translation is a key element’.[3]