Roy Orbison, ‘In Dreams’, 1963.

Sleepwalking can be an unnerving phenomenon. Your body has taken over your mind. Or is it your mind that has taken over your body? Something that is present is controlling something that is absent. This strange absent-presentness takes place, or present-absentness; a kind of haunting, or possession. You are there, but you are not really there; you (or a part of you) has offered up your somnolent body, your autonomy, to an unconscious layer of your mind. Something invisible is pushing itself up against the surface.

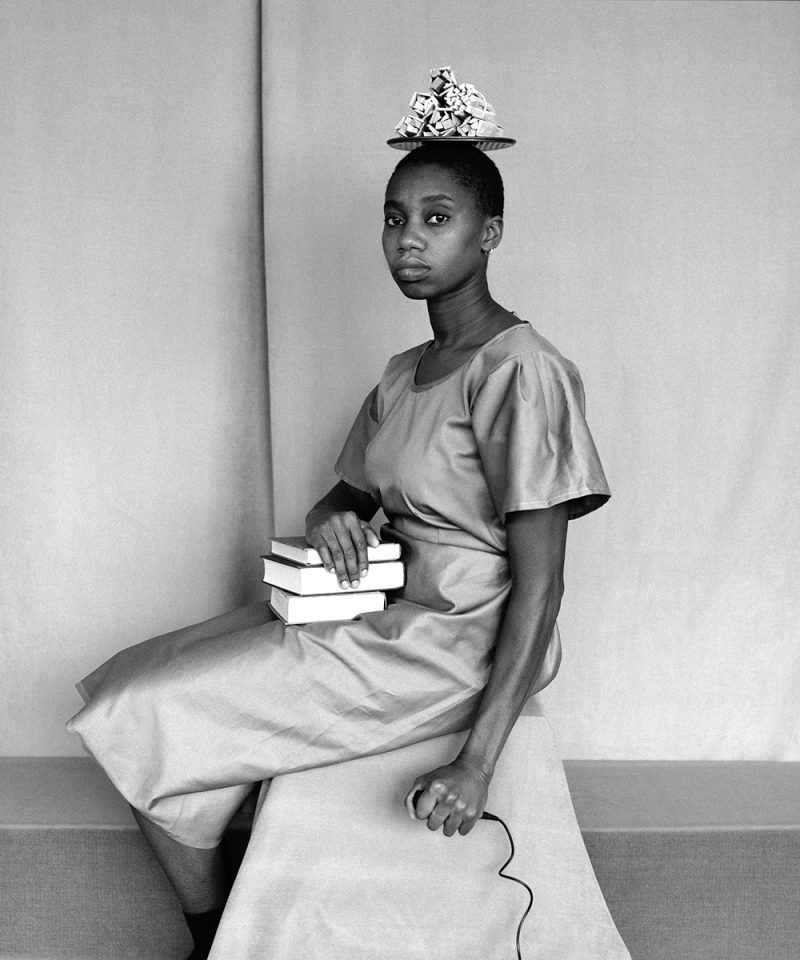

The Sleepwalkers (1959) by Arthur Koestler traces the history of Western cosmology and argues that the most revolutionary scientific discoveries emerge when the scientist surrenders full control of their research to a process that is comparable to sleepwalking. Koestler argues that the best outcomes are achieved when scientists allow the unconscious, irrational mind to guide them in a more creative way. It concludes that science today is overcompensating with its desire to be rational, to be aligned with reason, and therefore positions itself in opposition to faith or spirituality. This book provides the inspiration for the title of Theo Simpson’s commission for the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2020, Dark Interlude. This title is borrowed from a chapter of the book, in which Koestler explores the changing ways that people envisioned the shape of the universe; from being walled-in, to round, to flat. This philosophical line of enquiry into world-cognition – how we think of the world, how we see the world in its totality, echoing a kind of haunting, of being simultaneously present and absent – is one that Simpson addresses in his ongoing body of work. Geographically, his photographs have been shot in locations across the United Kingdom, but their abstraction in form conceals this from immediate view. Fragments of information are hinted at within their individual titles, but the power of the work is in its complexity to be both local and global, opening it up to interpretation and allowing the landscapes’ histories and how they are embedded within the present and future moment to be interrogated within a globalised context. In order to read them, we might need to sleepwalk too.

This piece thinks about how technology is explored within Dark Interlude and will be discussed in relation to control and technology’s gradual disappearance into our social, psychic and physical landscape. How can we think about haunting and notions of hauntology in order to read these landscapes? [1] How can we think of sleepwalking as a kind of haunting, and how does this connect to technology’s disappearance and control? Music is placed within the piece to conjure up a mood, and touch upon some of the ideas explored.

Actress, ‘Birdcage’, Ghettoville, 2014.

The scripts now carry tears, the world has returned to a flattened state, and out through that window, the birds look back into the cage they once inhabited.[2]

On entering the gallery, one of the first effects felt is that of confrontation – a looming steel structure, like an austere climbing frame, cattle gate or circuit board that has been stripped back and scaled up, imposes itself at the entranceway. Acting as both partial divider and as a mechanism to contain six works, its presence enforces a sense of order within the gallery as the viewer is obliged to be directed by it and interact with it. This regulated space reproduces an environment of enclosure, explored most notably by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish (1975), who traced the birth of the prison and how its mechanisms have bled into other institutions to exert discipline – such as the school, the factory, the mine, or (when considering Actress) the birdcage. Their apparatuses force those living or working within them to be subservient to the hegemonic mode of governance. In ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’ (1992), Gilles Deleuze updates Foucault’s argument to reflect how control manifests within contemporary society and highlights the erosion of these spaces of enclosure, where the factory has been replaced by the corporation: “Enclosures are molds, distinct casting, but controls are a modulation, like a self-deforming cast that will continuously change from one moment to the other, or like a sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point.”[3] This points to a flattening of power and the rise of a neoliberal subject, that is individualised, self-regulating and living in a networked society where control still exists but has embodied a new, ductile form. To sleepwalk is to lose rational control and becomes a necessary means to both uphold this system and survive within it.

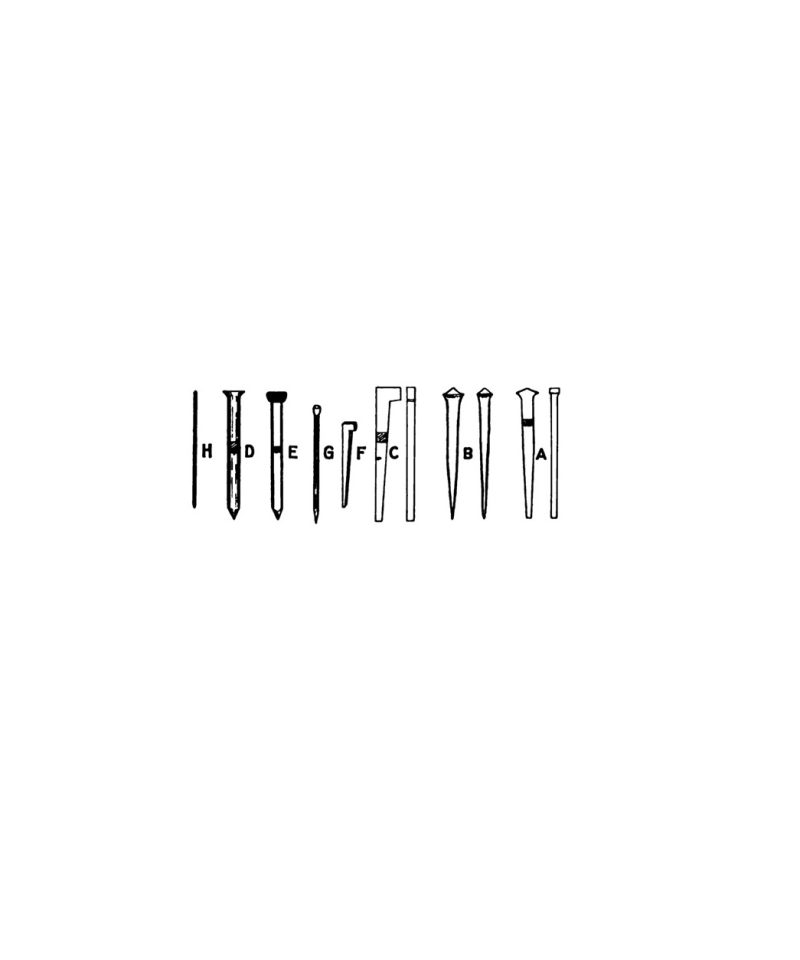

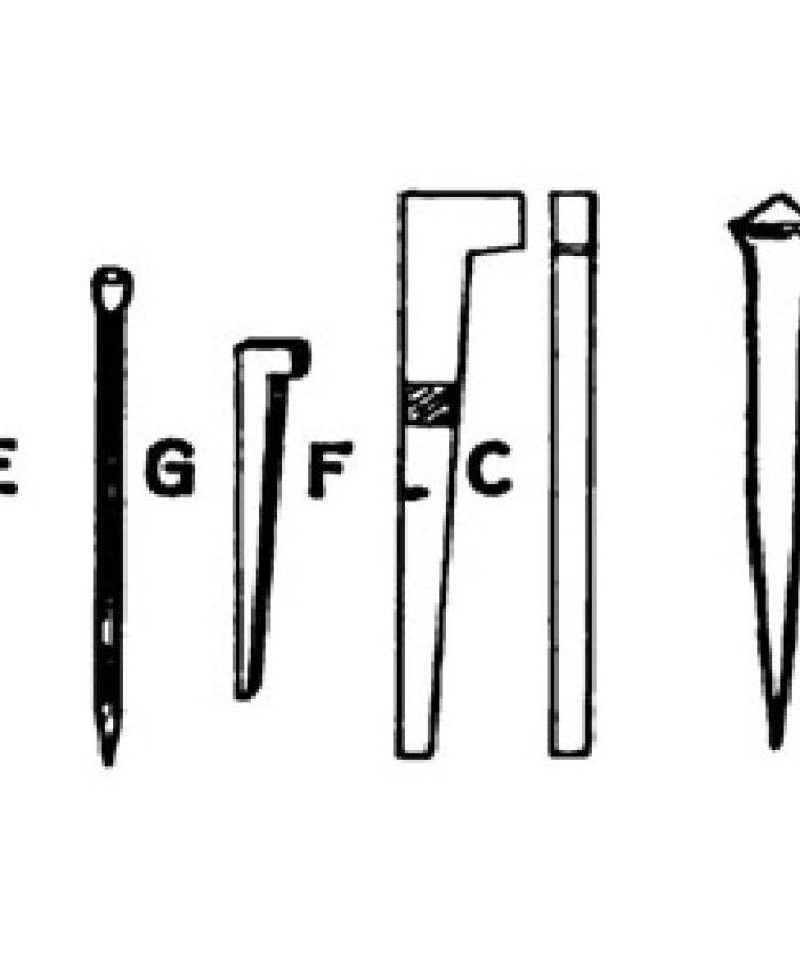

In the context of Dark Interlude, the rigidity of spaces of enclosure is echoed within the framing of the works, both within the wider gallery space by using a dividing structure and through Simpson’s use of of the ‘chassis’ to encase individual works, an engineering term that refers to the framework that a vehicle is built upon. The rungs of the dividing structure serve as a physical and metaphorical central connection point between the works, demonstrating the relationship between them, and pointing to Simpson’s versatile practice that operates as a continuous body of work. The structure of the frame is fixed, but the artist re-arranges which and how many works are displayed accordingly. For Dark Interlude, six works are mounted onto the apparatus with two additional frames left vacant. This malleability gestures to its state of being in motion, in mutation, nodding to Deleuze’s theory of a control society, in which modes of power are continuously adapting and reforming. Control is adopted to impart a sense of authority but it also alludes to the method in which Simpson creates these works. They have a feel of slick precision, a reminder of the role the machine has played in making them, rendering the human hand invisible from their production. Third Shock exemplifies this – a sculptural work that is geometric in form, its ripples emulating a hybrid between a wave in motion or mountainous landscape with a futuristic car part. Sheet steel is cut up and painted a shade of Lotus Bermuda Blue, a car colour that was popular in the late 1980s. The reflectivity of the metallic surface coupled with the three-dimensionality of the work creates something that is simultaneously organic and mechanic. Its title refers to the first and second oil shocks of the 1970s when an embargo was placed on Middle Eastern oil, causing shortages and driving prices steeply up. Third Shock imagines the chaos that such an event would incur on society today, one that so heavily relies on the availability of oil, pointing to the economic and geopolitical power that it holds, and provokes a sense of threat.

Whilst physically asserting control within the space and individual works, other forms of social control are referenced within Simpson’s work, pointing to a wider discussion around divisions within society; whose bodies and what narratives are controlled and how does this enforce division? when it rode upon men references the miners’ strikes of 1984-5 by reworking an archival image from this time. The black and white photograph has been abstracted to such a point that the content is largely discernible, as though it has glitched and blurred. The subject matter becomes both present and absent through the obscuring of form, producing a kind of haunting or spectral entity of the image itself. Cutting into the image’s horizon is a wide block strip of colour – one quarter bloody red with burn-like marks that singe the edges, and three quarters a deep blue that fades into a sky blue as you track it along the opposite direction. By retracing and obscuring this moment in history that marked the decline of the British coal industry, Simpson is pointing to the lasting significance that these events had and that are still being felt in former mining communities. The scandal of the Battle of Orgreave, a violent confrontation against the strikers by the police in June 1984, is still being played out today as the police’s actions were never held to account via an investigation, despite ongoing campaigns for a public inquiry. Sarah Champion, Labour MP for Rotherham, stated that Orgreave “is not something in the past, it is a living wound.”[4] In Capitalist Realism (2009), Mark Fisher argues that the miners’ strikes “fully exposed the fault lines of class antagonism.”[5] This defeat, according to Fisher, was a significant moment in the development of capitalist realism – that there really was, according to Margaret Thatcher’s catchphrase, ‘no alternative’ to this economic and political system; the ideology of neoliberalism had won. By re-presenting this turning point, Simpson is opening up questions around how we can re-think these moments that had such possibility but that ultimately resulted in a failure to prevent the emergence of neoliberal global capitalism, which has become deeply entrenched within society.

Burial, ‘Near Dark’, Untrue, 2007.

We have been conditioned to think of the darkness as a place of danger, even of death. But the darkness can also be a place of freedom and possibility.[6]

There is a sense of loss within Simpson’s work that is unshakeable, a loss of industry that haunts the landscapes from which the works are drawn, embodied in the sites of the factory and the mine. Since the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), machine technology developed and pushed the traditional factory worker out, and as technology has progressed further, it has gradually disappeared from our peripheral vision and seamlessly merged with our everyday experience, as the society of control has encroached upon the social landscape. In Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s The Soul at Work (2009) the increasing alienation of the human condition exacerbated by new and seemingly never-ending ways in which we are always on, always working, is explored: “Labour has lost any residual materiality and concreteness, and the productive activity only exerts its powers on what is left: symbolic abstractions, bytes and digits, the different information elaborated by productive activity.”[7] These concrete forms of labour have become ghosts.

Despite an increasing dematerialisation of technology, Simpson champions materiality within his practice by foregrounding industrial materials and their engineering processes whilst exploring the role that new technologies have on society. This can be observed in Process 1, a sculptural work that comprises a chromogenic print of steam from a cooling tower that is positioned within a channel and encased by a steel, green-painted console. The steam, however, could be interpreted as smoke from a fire, a warning sign of the climate crisis that is beginning to materialise in plain sight. The form of Process 1 has been influenced by conveyor systems and processes of automation that have given rise to smart factories, and its technical perfection evokes the type of factory it could have been manufactured in. These new categories of factories – increasingly automated and devoid of human labour – are becoming integral to manufacturing processes, and by referencing them, Simpson is envisioning their increasing dominance within the industrial landscape. With Silicon Valley becoming the global centre of technological development and its monopoly on the market, it can be tempting to slide into a techno-pessimistic point of view; information technologies have both liberated and imprisoned us into their networks, and they open up a multiplicity of endemic problems.

Theo Simpson’s work is neither nostalgic nor mournful; instead, it provides an opportunity to reflect and sense the possibilities that these landscapes still contain, that they are haunted by. Simpson reminds us that the world is in a constant state of motion, of progression, of moving forward, and although there are inevitable threats amongst these seismic and unpredictable changes, there is also a sense of hope. By bridging a gap between industrial techniques and artistic practice, Simpson is offering to us a meditation of the future. Both his and the scientist-sleepwalker’s practice could be summed up by Franco “Bifo” Berardi: “only an alliance between the engineer and the poet might reverse humanity’s slide towards self-annihilation”.[8]

James Blake, ‘Assume Form’, Assume Form, 2019.

[1] Hauntology is a term coined by Jacques Derrida (in Spectres of Marx, 1993) to demonstrate how the present is entangled with both the past and future. An always-already existence is embodied in the figure of the spectre, who can never be fully present. Derrida deconstructs ontology (the study of the nature of being) and calls upon the notion of haunting and spectrality to demonstrate that “time is out of joint.”

[2] Actress, Press release for Ghettoville, released 27 January 2014, https://ninjatune.net/release/actress/ghettoville.

[3] Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, Vol. 59., 1992, 4.

[4] David Conn, ‘Thirty-five years on, Orgreave campaigners still seek justice,’ Guardian online, 27 June 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/jun/15/thirty-five-years-on-orgreave-campaigners-still-seek-answers.

[5] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? , Zero Books, 2009, 13.

[6] James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, Verso, 2018, 15.

[7] Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Soul at Work : From Alienation to Autonomy, Semiotext(e), 2009, 75.

[8] Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Breathing: Chaos and Poetry, Semiotext(e), 2018, 8.