On Thursday night, Naheed Raza was the focus of the ICA’s Artists Film Club. The audience gathered in Cinema One for a screening of Sand (2010) and Frozen in Time (2013), which was followed by a Q&A with me. The two works acted as an interesting foil to one another: Sand, which was commissioned as part of the Bloomberg Comma series, is a short, silent, film (shot at the edge of The Empty Quarter in the United Arab Emirates) which meditates on the power of the desert; Frozen in Time, meanwhile, is a longer, video work that investigates the practice of cryo-preservation through interviews with a number of its advocates in America.

I began by asking Naheed about her background: having read medicine as an undergraduate, she went on to study Fine Art at Chelsea and the Slade and I wondered at what point she began making art and when she decided it was something she wanted to pursue professionally.

‘I suppose I have always had these parallel interests’, she explained. ‘I was fascinated by medicine and the sense of it as a total subject… the idea of needing to understand the being at a micro and macro level, the sense in which there are these worlds beneath the surface that one only becomes aware of when the normal homeostasis is tipped into disequilibrium. I had this feeling of wonder about the body as an incredibly complex structure that can be traced back to quite simple laws.

‘At the same time I have always had a very innocent enjoyment of art. It’s an activity that I would spend many hours doing and I loved the sense of transportation that it gave me. Growing up, it never entered my mind that it was something I could pursue professionally so I followed the scientific path and I suppose it was only once I was studying that I suddenly realised quite how important art was to me. I started to attend lectures at the Ruskin [College of Art, Oxford] and that’s when I first encountered artists’ talks and I was intrigued by the ways their ideas were manifested in their bodies of work. I sensed quite urgently the need for me to pursue this interest.’

It was nice to hear Naheed talk about her journey into filmmaking, not least because the sense of ‘wonder’ that she described is so readily apparent in her work. She has spoken previously about craft as one of the areas of commonality between medicine and art – two disciplines that are so often stereotyped as antithetical to one another. We might also think of the shared importance of observation, of a thorough understanding of anatomy and of the ability to intuit meaning from a subject. I was interested in pursuing the place of intuition in Naheed’s work and asked her how she had found the experience of conducting interviews for Frozen in Time, which is the first time that human subjects have featured in her work.

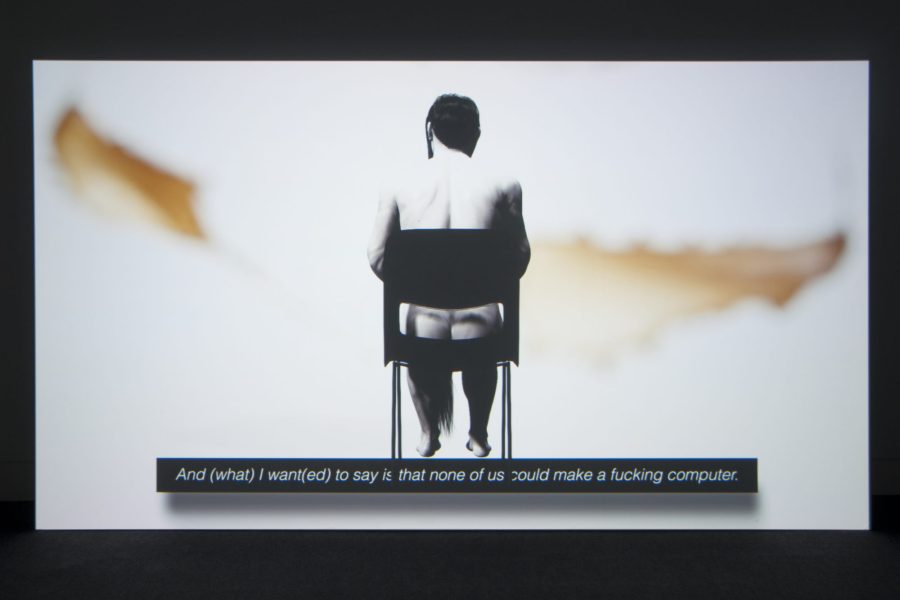

‘I approach film from a very sculptural background, from an interest in material and process. I have a fascination with the idea of perpetual transformation and the idea of intuition is very important to this. Having studied medicine at Oxford in a very formal way, when I first went to art school something I was keen to get away from was this rigorous structure to learning and knowing, I wanted to abandon any logical way of thinking and instead respond in an intuitive way to material. Within the early works, I wanted to place the viewer in a position where knowledge or language might not be very useful; where there would be no props to hold onto so they would have to respond to what they see. Because of habit, we no longer see to a certain extent. There are moments – ruptures – when we have a very primary engagement with our environment, but these are rare.’

‘Frozen in Time, as you say, was the first time I had worked with people. There were themes I felt I was approaching from earlier works: an interest in entropy, the desire for permanence, the belief that we can produce concrete, lasting entities. It struck me that this was a subject where individuals were reacting against that process and that was fascinating – it was the opposite of everything that my work had been about. It was interesting to speak to these individuals because one can relate to them.

‘It’s important not to mock even though Cryonics is a subject that can quite easily be ridiculed. What they are articulating are quite primitive fears and desires. Death is one of the most difficult ideas to comprehend or grasp, and in a society where there is a vacuum of faith, death can seem like an absurdity. In terms of the material it was really challenging – I am used to working with material that I can shape, either with my hands directly or through the editing process. Suddenly, when you are dealing with people, you have these bricks that are preformed.’

This felt like a natural moment to comment on the composition of some of the shots and, in particular, the recurrent use of the profile. For me, this seemed to act as a reminder to the viewer that there is someone off-screen asking questions – indeed, at one point, one of the interviewees says ‘let me turn that question back around at you’. The talking heads are inter-cut with atmospheric shots of the cryonics institute, which act like caesuras, creating little spaces for the viewer to reflect. It feels inevitable that in these moments, as the mind wonders what should be believed, that we also wonder what the artist believes…

Understandably, Naheed was quick to explain that ‘it’s important to keep that quite elusive’, but she was generous in expanding on her mixed feelings about the subject.

‘Coming to it with a scientific background, I do feel that the challenges of bringing a being back are enormous, especially given that we still know so little about consciousness. Even something like sleep baffles us: we might be able to take electrical recordings of the brain during these activities and recognise or code certain waves or patterns that we see but we are no nearer to being able to translate what that means. There is still great debate about consciousness too. With Cryonics, they look at the matter from a reductionist perspective, saying that structure equates function but it’s not that simple, we can’t locate a structure within it…

‘On the other hand, there are extraordinary examples within biology of organisms that are dormant for thousands of centuries, a spore, for instance, is dormant for long periods of time and I think that forces us to question the definition of “alive”. One of the character’s talks within the film about “what’s possible” and there’s a sense in which we’re losing this idea of possibility. We need to be reminded that there are these limits of knowledge beyond which we can’t be certain of anything.’

This idea of possibility is perhaps what Naheed creates space for through the rhythm of the edit. These are also pauses in which the viewer can become aware of themselves as a living, breathing, pulsating being – something that we tend not to dwell on. For my final question, I asked Naheed how much she thinks about the viewer and their response when she is shooting and editing her work.

‘I create those pauses for the audience, but also for myself. Editing for me is this quite intuitive process – there are correlates, for instance, between the length of time that we can hold our breath and the length of time that we can watch a shot. I like to play with those limits and a sense of the body helps in how I structure the film. Throughout the work there is a move from speech to silence and from flesh to machine and there are these recurrent reminders of bodily processes’.

At this point, we opened up to the audience. There were a number of brilliant questions: probing about subjects ranging from the financial implications of subscribing to cryo-preservation to the afterlife of a video work like Frozen in Time. I was delighted to have shared the stage with an artist as sensitive and thoughtful as Naheed, and left the ICA with the distinct impression that this might have been one of my best Valentine’s dates to date.