At the talk held at Jerwood Visual Arts on 23 November (Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2015: Matthew Finn, Joanna Piotrowska and Tereza Zelenkova in conversation with Martin Barnes), Matthew Finn said he wouldn’t recommend the way he works: over long periods of time spent in close proximity with family members and that only end when life or a certain way of living concludes. Finn’s Uncle series terminated because it had to, at the point of his uncle’s death, and he was forced to finish photographing his mother (for Mother, 1987-Present) when she moved into an assisted living residence – out of the family home she and Matthew had shared and which served as the setting of his photography of her for more than twenty five years. I found it humbling to stand in front of a body of work that had been in development for longer than I have been alive, and that had been built up in private according to a different, much slower pace than the one at which I tend to work, in the compromised time of unrelenting deadlines. The idea of slowing down holds a lot of appeal right now, the idea of having to stop because of a death or other form of loss of course much less so.

Without asking Finn, it’s unknown if the final photograph taken in the series has been included in the display at Jerwood Visual Arts. Nonetheless, after the talk I went to look at Mother for a second time and found myself trying to locate a possible ending amongst a non-chronological extract of a vaster body of work. The edit that Finn presents takes in his varied approaches to representing his mother, by means of conventional portraiture as well as through objects such as domestic appliances and food, all of them black and white and fairly small scale, like the favourite photos of a family album, a few plucked out, slightly enlarged and hung in frames in a household hallway. From the available selection, I narrowed down the final photo to one or two. Could it be the square format photograph in which the absence of Matthew’s mother, Jean, is most keenly felt? Empty frames within frames: light shines through French doors and another two sets of doorways before falling onto a clean expanse vinyl wood-effect flooring, also empty save for a Henry hoover that assumes the subject position taken up by Jean in most of the other pictures. I focused in on Henry’s eyes, obviously expressionless though I charged them with guilt for having vacuumed up all evidence of Jean’s clothing, home decoration choices and habits that are in abundance in several other shots: tomatoes ripen on a lace curtain-framed windowsill; Jean sits in the sun and drinks a glass of water while holding a lit cigarette; the sofa Jean has drifted off on is striped and made of velour.

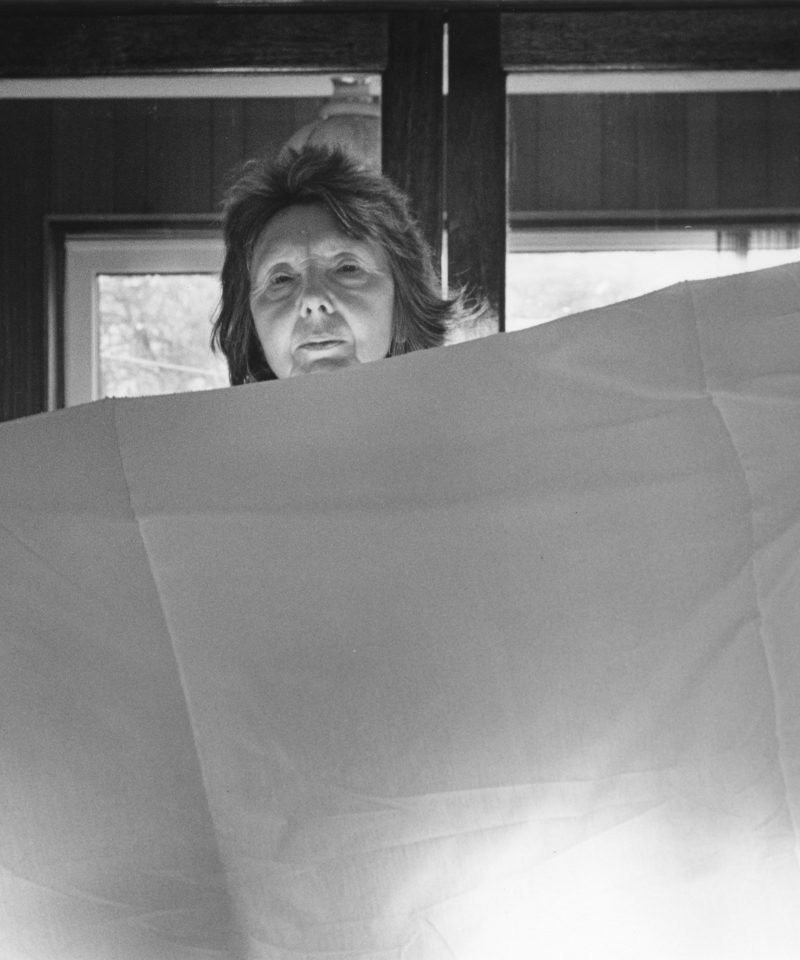

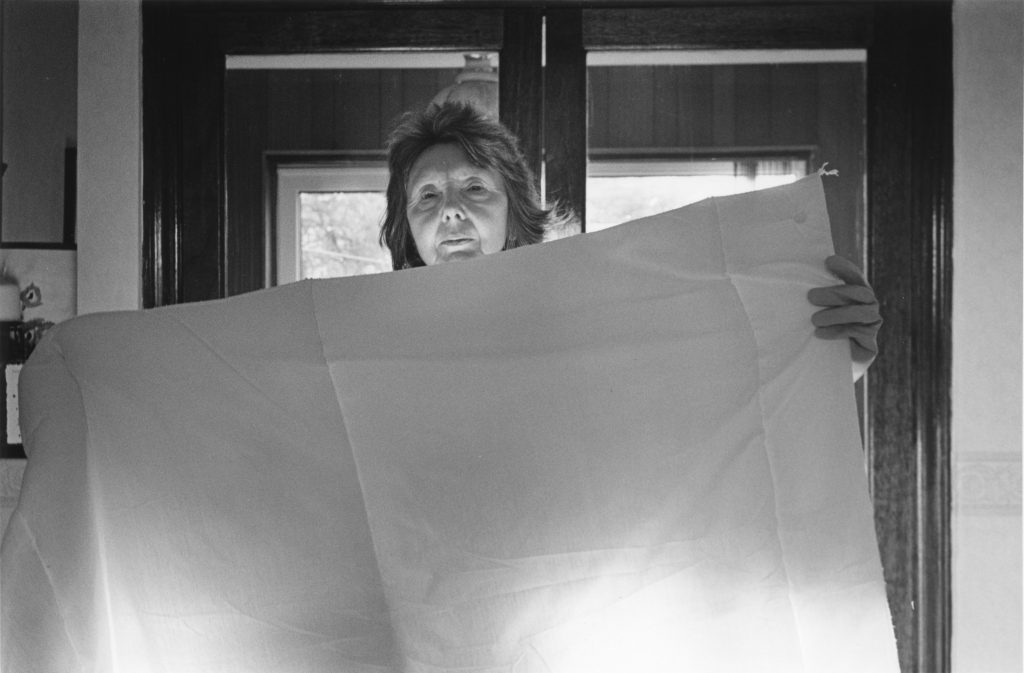

Or, perhaps the final photograph was the contrastingly cluttered square format photograph in which Jean is slumped sideways in a chair pulled up close to a wrinkled bed. She is surrounded by her own small collection of photos, clustered together on top of a chest of drawers. It’s the only photo where she looks diminished and unwell. I imagine that continuing to photograph her from this point would have been too much of an intrusion, too exploitative to carry on. (In the talk, Finn cautioned against the photographic tendency to aestheticise or blow up images that emphasises human distress.) In many other photos Jean faces the camera, or is more clearly conscious of its presence: as poised as a dancer as she stands between washing machine and fridge in her galley kitchen, head on a tilt to show her ‘best side’. In another photo she stretches a bed sheet out beneath her chin as a photographer’s assistant might hold a reflector, clearly aware of the ways in which light can be flatteringly employed. She appears in charge of her own composition, acting the part of the woman she wants to see portrayed.

Despite Jean’s apparent comfort with the camera, Finn said that he worried about exhibiting this work: his difficulty has been in bringing something so intimate to a broader audience – ‘What happens when you make something that is so personal and that yet has to distance itself from the personal in order to open out beyond the individual who has made it?’, he asked. I know that many artists and writers share this worry of overexposure or that sharing something apparently intimate may be met with derision or dismissive charges of narcissism and self-obsession. It’s a problem with deep roots that art historians and critics have contributed to – Rosalind Krauss for example: In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson recalls the graduate school seminar she attended in 1998, in which Krauss responded in an outrageously belittling manner to Jane Gallop’s new work. Gallop presented a slideshow of naked photos of herself and her son – Nelson recalls that:

‘She was trying to talk about photography from the standpoint of the photographed subject, which, as she said, “may be the position from which it is most difficult to claim valid general insights.” And she was coupling this subjective position with that of being a mother, in an attempt to get at the experience of being photographed as a mother (another position generally assumed to be, as Gallop put it, “troublingly personal, anecdotal, self-concerned”)’

Where Nelson thought Gallop was ‘onto something and letting us in on it before she fully understood it. She was hanging her shit out to dry: a start’, Krauss ‘excoriated Gallop for taking her own personal situation as subject matter, accused her of having an almost willful blindness to photography’s long history.’

Krauss’s stance seems so outdated and yet we continue today to have to battle against such a stance. Finn needn’t have worried – the personal nature of his work makes it no less relevant to others. It’s prompted me, in the week or so since viewing it, to look again at the mother-son work of Leigh Ledare and to search online for clips of No Home Movie, 2015, the mother-daughter last work of Chantal Akerman which emphasises the role of the camera and the ways in which different technological filters can affect child-mother relationships – how a mother can be be brought closer by video services like Skype, the physical distance imposed by Akerman’s travels minimised. Spending time with Finn’s Mother also made me reflect on the host of mothers I’ve been reading about lately; besides The Argonauts I’ve just finished Jenny Diski’s travelogue-memoir Skating to Antarctica, in which she describes a troubled family history and estrangement from a mother of whom she owns a single photograph. Diski’s family album was also lost – entrusted to a man who worked in the boiler room of the home her mother hastily moved the family out of, and never saw again.

Finn’s Mother is perhaps first and foremost about avoiding loss – capturing as close as possible every moment – he even had a camera in hand while watching television with his mother and once caught himself watching TV through his camera’s viewfinder. The series has also been about control: Finn said that part of the motivation behind Mother was about taking charge of the representation of his reduced family (he’s the only child to Jean, his single mum). He had been looking at family albums and at what happens when families break up – as Diski’s book testifies, the family album gets broken up and he wanted to create a ‘safe’ album: an album that would at once be his own and that could also be shared in exhibitions. I think of Mother’s audience becoming members of an extended family.