Hi Alice

Sorry I meant to wish you the best for the talk. How diid it go? Mx

p.s. Tour not talk

Hey Marianna –

You’re probably right: it was more ‘talk’ than ‘tour’…

I’ve been talking to Marianna and Lucy via email, the real life interview in and amidst the intimate documents of epistolary performance. Some of the emails are visible here, and some of them are buried in the flow and fissures of the text. To keep some bodies private.

I read the imaginary letters to M and L out loud for a gallery ‘tour’ last month, an extension of the performance, spawning questions in the post-discussion about writing and embodiment, liveness and vulnerability. We were talking about talking, essentially.

This particular document will be longer than I first intended: it will wander and accrete, out of linear time, as text feeds more text, akin to the course of correspondence between friends. It only stops when someone stops writing.

Or dies.

*

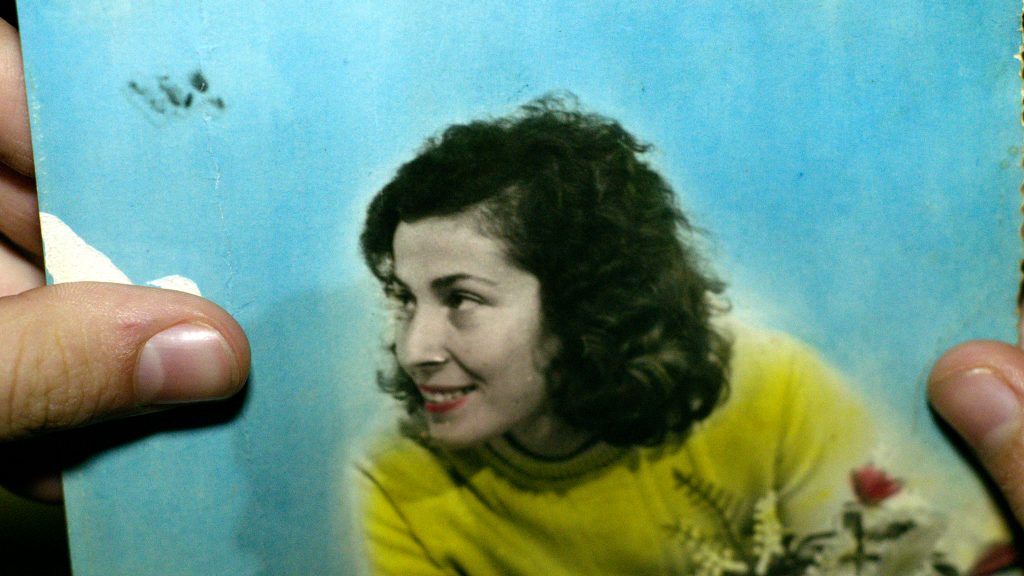

In Marianna’s Blood, language becomes a sticky transparent substance that bends across geographical boundaries and dialects. Subtitles are there to help us but Isabel doesn’t need them. She understands Lali without these directional flashes of conversation. Their interlocution is much more intimate, and embodied. It’s not just heard, processed and interpreted; it’s also felt, and left hanging, almost unanswered. As if it’s happening in the moment. As Isabel asks Lali questions like ‘what shall I call you, a he or a she?’ the young girl interviewer tests and excavates the template of her (and Lali’s) subjectivity and public appearance. Their talking is based on a language of discovery and desire, what Ann Cvetkovich in her ‘public feelings project’ would call ‘queer bonds – forms of intimacy that have public significance that transgress boundaries between work and play, and remake the meanings of love and kinship.’

We see similar bonds being played out in Marianna’s ‘conversation-research’, which saw her meet and talk to numerous sworn virgins (not just Lali) while volunteering as an English teacher in an Albanian school. In a snippet of a filmed interview, sent to my inbox as part of an email of ephemera, I listen in on Marianna and Drande, with translator, discussing ‘what is a man?’ Drande, in a stripy polo shirt, plays with his cigarette paraphernalia while outlining the character of ‘man’: being honest, being fair, he says, assuredly through the smoke.

March 27 2015, 10:54 AM, M writes:

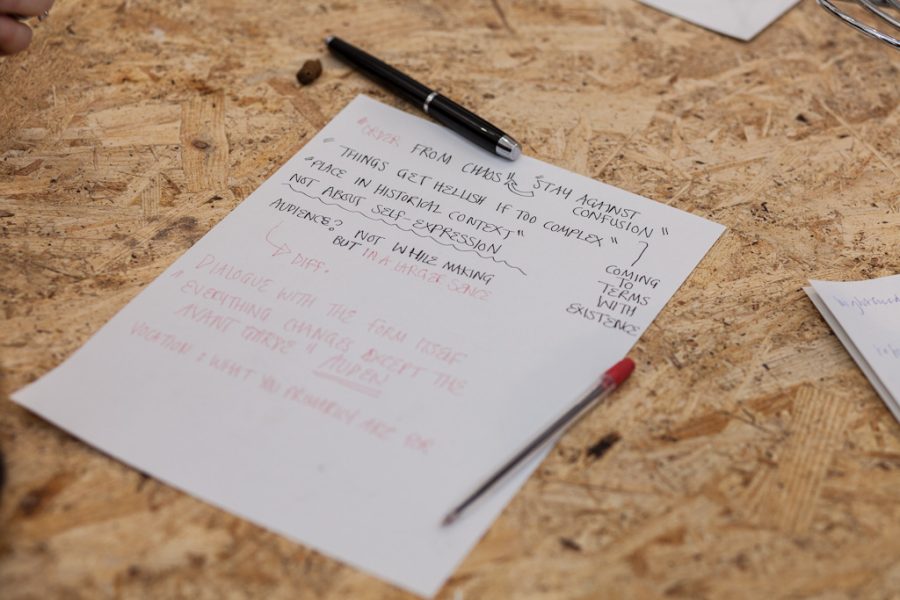

The process for each scene is governed by the situation. Some is tightly scripted but often based on conversations and rehearsals. Sometimes a rehearsal isn’t possible so it happens on set, like in the men’s scenes. The remoteness was difficult, not being able to see or predict in advance. But of course that’s also why I do it. You ask a northern Albanian to talk about besa or blood and they’ve already got a thousand things to say. The scene on the bridge, where Isabel is asking Lali questions, was actually me feeding the questions and improvising with them… it was akin to a live performance for camera with four speakers, not two: the cast, the translator and myself. As for the friends/bones, they are real best friends from school. I would try to eavesdrop during rehearsals, try to catch moments when they are not heard by adults.

(Later, M wrote: Talking is less important in the film that communication of which there are many kinds.)

On camera and backstage. The cast-sheet of Blood reminds us of the presence of the translator, the out-of-sight communicator. It is a ‘he’: a 25-year-old electrical engineering student born in Kosovo. His hands creep into the frame in the final scene, his words into the audio: he too, is character, and crew. There was a translator on the research trip, too: a tricksy one who wanted to be an editor, tampering, then fixing, the script via Facebook chat. It took 6000 fraught but funny messages to build it.

In Blood, conversation is exposed as a constructed encounter, an inquiry but also an unpredictable performance, where semantic accidents might occur. Moments of ephemeral everyday language are reoriented in fictional scenes of noise and chatter, as Isabel’s turbinate bone hysteria is also located in the mouth. (‘She’s the unorganizable feminine construct’, wrote Cixous of the headless (and boneless) hysteric.) Isabel, strewn and static in her pink puffy hammock, but busy and manic in her dreams, is a fictionalized subject of the Freudian object-fiction: Emma Eckstein, to be specific, a patient of Freud, who had her preturbinates removed as a treatment for her warbling madness and junkie masturbation. Freud was heavily influenced by Wilhelm Fleiss, an ‘otolaryngologist’, who saw a link between the leaking nose and the leaky genitals. Marianna urged some private surgeon specialists to see beyond the medical misinterpretations and historical inaccuracy, Isabel being an innocent 10, as opposed Emma’s sex-crazed 27.

(I later take a peek at Marianna and Cecilie’s correspondence of black, red and purple font, the texts’ changing colour a suggestion of the journey of ideas and the multiple voices of production. The clinician from W1G must’ve said no, unsurprisingly, as the hospital location moved to a state of the art ear-nose-throat surgery in the West Midlands: The hospital is a small one, Marianna wrote first, hence the easy admin – not ideal for transporting crew, but then it could be worse… it could be Albania.)

Emma E had her revenge on Freud, when she stole back the analyst’s pen and started practicing in the job herself, just like Isabel running free, running blood. Or Lali choosing to give it all up and live her life as a man.

Or Marianna writing in her notebook.

The availability of choice is the most important thing.

I should admit that I grew a beard when I was making the film. (Marianna, artist TALK, 20 April 2015, about 7:30 PM.)

*

The figure of the mad woman-writer (of novels and letters) is in a constant battle with her masculine analyst. In October 1959, the then night-time novelist Ann Quin took up her post as part-time secretary at the Royal College of Art (she was a crazy fast typist), after being cleared fit by her doctor. This would later become more tenuous, as her doctor would become more doubtful, mirrored in the note-writing analyst character of Dr. X in the The Unmapped Country, the novel she was working on at the time of her death. ‘I’ve got the pen here. Do you see the pen?’ He questions the patient, waving the phallic tool in her face.

She longed for the pen, but was inscribed as record instead; forced to work behind a docile desk, to be made answerable to Sir. Made into ink. Unable to resume duties.

Before she wrote it all back into her fictions.

‘Freud’s’ Anna O. (formerly Bertha Pappenheim before Joseph Breuer renamed her) crafted her own fairytales too. She wrote, told stories in ‘babbling polygottal’ tongues, even if no book survives for feminist posterity. Kate Zambreno talks about in Heroines: ‘The hysteric is a writer who ultimately could not be,’ she wrote, in 2012. The hysteric’s chatter is disruptive, unrecognizable and infinite, located beyond the lock-and-keyed archive.

18 April 2015 10:59 AM, M:

From what I can gather Emma E was a tough nut. She took the piss out of Freud for weakening at the sight of her haemorrhage. “So this is the strong sex”, she said to him after almost bleeding to death. Emma E. has been overloaded with irritating and damaging theories regarding her condition… but this is a larger problem to do with hysteria and women. What caught my attention was that she was thought to have conjured her own blood… like Matilda… making stuff move that shouldn’t. According to Freud she wanted her bleeding problems to happen so she could get his love and attention. This all sounds like bullshit, but the idea of eliciting a fluid seems plausible. Her body willing it… being ill can be a desirable place to be and may not necessarily be synchronous with passivity.

To be illful and willful simultaneously:

M: This film felt very much about the retention of blood and the ill of willfulness. Check out The Willful Child by the Brothers Grimm. Sara Ahmed mentioned it once in a talk and it’s haunted me ever since.

I look up the fairytale and find it online in both ‘he’ and ‘she’ versions. I read the latter. In this pithy tale of infinite pathos, ‘God’ punishes a young girl for being naughty and willful; he lets her become ill and does not stop her from dying. But, as she is lowered into her grave and her body becomes smothered with earth, the child stretches her arm upwards, out from the ground and into the sky. Her arm is relentless. She revolts against her own fate over and over again.

As Ahmed writes in Willful Subjects: ‘The arm that keeps coming out of the grave can signify persistence and protest, or perhaps even more importantly, persistence as protest’. Ahmed goes on to reference the clenched fist as a defining image of the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s, and that remains a characteristic signifier of feminist struggle.

Marianna’s film moves in and around this history.

*

I wonder if the email is an epistolary form particularly suited to the ‘hysteric’, the woman who wants to make her body known, heard, without the pathologist’s inked judgment. Fingers quiver, shake and scuttle above the keyboard, free and loose. Making a mess in more ways than one. It is writing that is both in time, and curiously beyond it, once it gets sent.

Babbling through message feeds: five conversations at once, breaking linearity.

Writing, as if talking.

Seemingly ‘unthought’, to write an email is a performance of the visceral and automated: the body channeling its madness in text that reads like speech. Relentlessly oral: keeping in TOUCH and interlocuting.

The private email is a mode of correspondence the hysteric can claim back and territorialise as her own. As Dodie Bellamy writes in the essay ‘Low Culture’: ‘Sitting at the computer, a body writes about sex. The keyboard and monitor are enormously erotic THE BEEPING MODEM, THE WORD MACHINE TALKING BACK more than once e-mail has gotten me in trouble.’

*

Trouble = Kathy Acker

I’ve been reading (or perhaps I should say: gorging on) the emails Kathy and McKenzie Wark exchanged over the course of six months between 1995 and 1996. The private made public. Her affective words are splashed across the cover in a typeface that mimics the handwritten letter: I’m very into you she once wrote, on screen, not on paper. Sometimes they would email up to six times a day, often seventeen hours apart.

Acker was to die at the end of November 1997, while staying in an alternative treatment centre for the cancer that was eating her (partly it was all she could afford, as she writes about in ‘The Gift of Disease’), and so she is no longer here, to halt the publication of her intimate documents. Perhaps she would have favoured it, seeing it as an extension of the performance she had been writing since she self-published in serial format The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula in the early 1970s. She borrowed her friend Eleanor Antin’s mailing list (comprising the same addresses Antin used for the post-card piece 100 Boots) and sent Childlike chapbooks as gifts of correspondence. In her published writing, Acker plagiarized her own life, and plagiarized others’ literature, creating novels of uncensored, disordered syntax. Selfhood is never watertight and whole. It leaks. It moves. It writes: confessing, naked and dirty.

Kathy met Ken (that’s how he signs off: k x) in Sydney in the summer of 1995. Ken was enjoying the success of his book Virtual Geographies, published a year earlier, which looked at the emergence of a global media space as a series of events, transmitted via various lines of communication, as rampant virtual spectacles. He was also juggling girlfriends and boyfriends, meandering in and around feelings of queerness and straightness, butchness and femmeness (which makes me think of Lali).

M: Lali offers a way of thinking through contradiction as a practical form of existence. She can walk into any toilet and be in the right one. She is able to switch her identity/identities on and off. She says she was born a man but what about the picture of her at the end where she looks like a woman? Her oath means she is forever alone but must occupy two genders. She is never settled. She agitates, always breaching her own fragile laws.

In Acker@eworld’s messages to mwark@laurel, she writes in a frenzied, but also direct, conversational style, calling to mind the candid statements about cocks and cunts spoken by many of her protagonists. She is skint. She is needy. She is nearly always drunk. She wants to talk, talk things over, if not with him, then maybe with herself, transcribed within the exciting medium of newness and first person intimacy = email. ‘Like: you the one I want/wanted to talk to’, she confesses, in the grips of the ‘beginning’ of their correspondence. (There is an edited narrative at play here.)

Ellipses litter the epistles, their only grammatical joinery (‘such are the delights of email.’) emphasising the blabbering, unedited hysteria of Kathy’s letter-writing persona: ‘… I love emailing you… emailing must be pure narcissism… I think I’m going to blab even more intensely now so byebye for tonight…’

Kathy doesn’t mind a colon now and then, though, as in: ‘Am depressed, a rarity for me, so want to blab a little. More: scream.’ These emails enable corporeal release.

As the prospect of Ken’s IRL arrival in San Francisco draws closer, Kathy’s anxieties over their epistolary relationship impels her to ask her correspondent questions, numbered and neat in format, but restless and manic in voice: ‘1. The last night we slept together, why didn’t you want to touch me?’ she enquires.

We might immediately sympathise with Acker’s plight of insecurity, but once again, she has constructed that trap, that ruse. It’s like when Zambreno wrote of the hysterical woman-writer – ‘She is raw material. Too raw, too open, too needy, too emotional’ – and flipped the appropriation as a positive tactic. And so, as Wark invites Kathy to ‘Write me your vertigo’, she does just that. Vertiginous and vulnerable emails they are, performed and worked out in her own time, as she talked in order to survive.

*

Kathy goes to Haiti, Acker’s short novel that figures a young girl’s sexual adventures in a self-sacrificing rampant form, was published in 1978, the same year as Hannah Wilke performed Intercourse with…, in which Hannah’s private phone messages (like Ken’s to Kathy’s) are transmitted to the audience in ghostly intonations, conflating intimate spaces of desire and confession with public spaces of fiction and performance. The voice-over stream of messages point towards the autobiographical, but this one-sided diary of phone calls – from family, friends, lovers and colleagues – has been cut up and reordered by Wilke, so that what we encounter is exposure, as owned and edited performance. Wilke then strips to reveal her body inscribed with the names of the individuals we have heard speaking, before erasing these signatures until all traces of their correspondence has disappeared – leaving only the outline of her naked corporeal figure. This is her reply, her post-script, much like Kathy’s final email to Ken: ‘Every time you dream I am fucking you, this is what happens.’

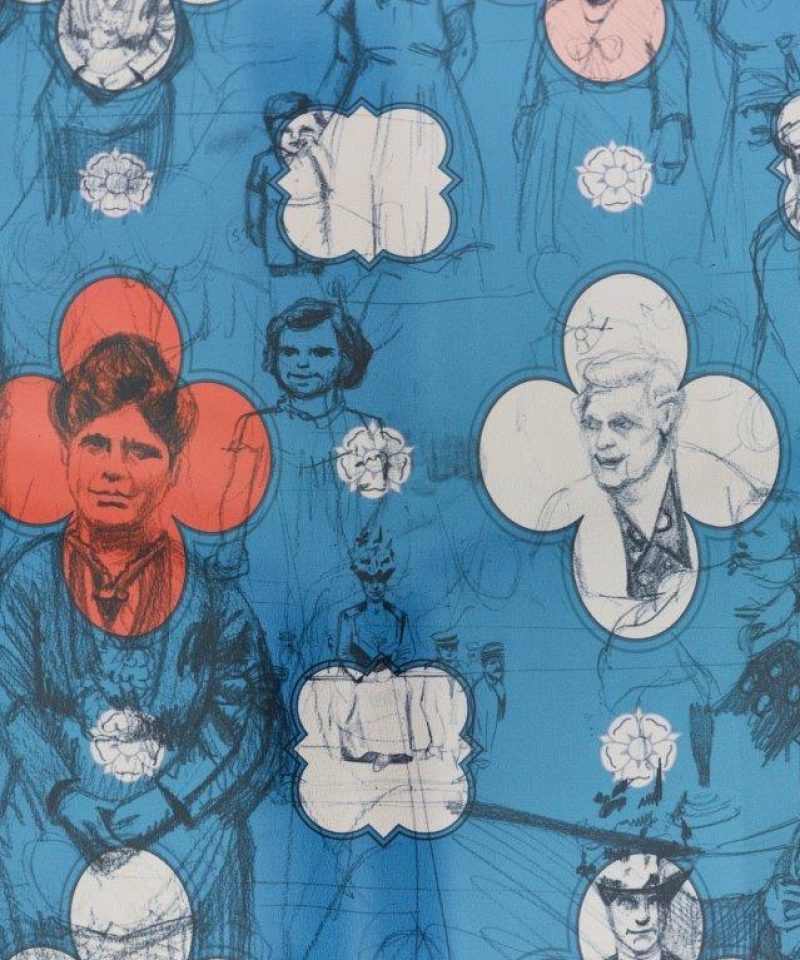

It also reminds me of the avatar that busies herself in hotel rooms in Lucy Clout’s film From Our Own Correspondent. She is an object, a performed cyber-being, an absolute example of a thirty something journalist with as an abundant inbox as Hannah’s answering machine. (But she asks questions for a living). The artist used the banal and suburban Next catalogue, and typed ‘professional work wear women’ into search bars, to design her regularised look.

22 April, 23.33 PM, L writes: There is something of the Holly Hunter in the film Broadcast News (1987) in her hair. She is older and fatter than the original version, and that scaling was tricky: the gusset was scaled particularly poorly at first. She wears these knickers of an almost towelling texture. I had in mind a type of foamy material that is used to make cheap everyday seamless underwear dense and absorbent. She has taken her skirt off in order that it doesn’t crease, or maybe she hadn’t put it on yet, signalling a half-readiness to perform. She is both rehearsing alone and running over her day, performing a looping type of stasis within the hotel room.

She’s offering herself too, her body and language promising distraction and interaction. TROUBLE? As she asks questions to get intimate, alongside her day-to-night profession, it is her written speech – her chatter – her talk – that defines her. But like the decapitated hysteric, she is curiously silent. Instead we experience her semi-naked body and her semi-naked chat-room messages: the correspondents’ private world (the correspondence) exposed.

L: The body is the filthy thing that disrupts the hotel room. (Lucy, artist TALK, 20 April 2015, about 7:40 PM.)

*

I’ve been thinking about the closeness of the word ‘course’ to sex, writing and correspondence. It’s a trial, an education: somewhere to test things out. It’s also a river, a stream, an interior scroll: of bodily and infinite messages: language. I mentioned Barf Manifesto in my first blog post, which is also a ‘letter’ to her friend Eileen Myles. Emphasising barfing and sickness as a feminist literary form, she writes: ‘The Barf is messy, irregular, but you can feel in your guts that it’s going somewhere, you can’t stop it, can’t shape it, you’ve just got to let it run its course.’

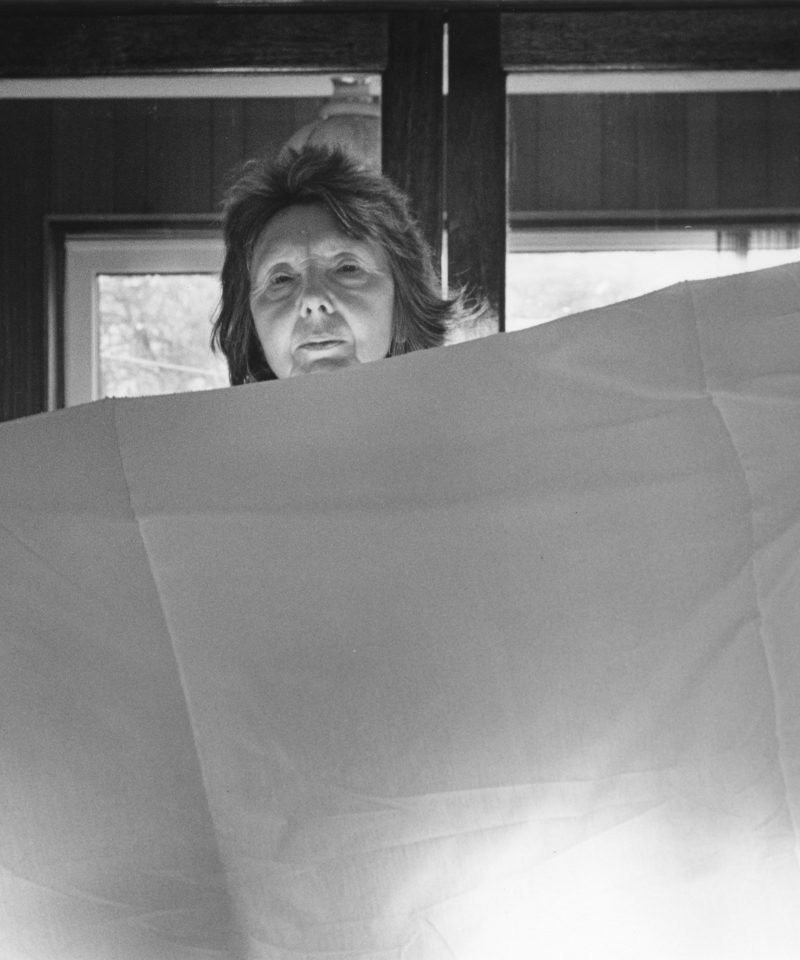

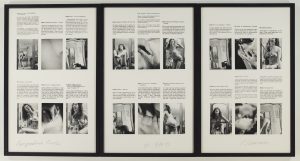

Correspondence Course is the title of an artwork by Carolee Schneemann, and a book of her selected letters. The written epistle – email or letter – is correspondence and the art object, as well as its very substance. Schneemann was sending out dotted and dashed TLS all over the place – to lovers, husbands, friends and artists – composing them on her Underwood manual typewriter, then photocopying them, and her correspondents’ replies, for her own future archive of work, performance and desire. But sometimes the letters she received were not always asked for; they were not preceded by a letter to. Excessive demands from scholars, administrators and bureaucrats agitated this usually enthusiastic and confessional correspondent, known as CS. The 1980 Correspondence Course is her reply of confrontational exposure: a teasing performance, in which CS bends her body in unexpected positions, maybe paired with a cabbage leaf beneath her vagina or clutched in her bum cheeks.

Comprising a series of eighteen self-shot photographic prints with fragments of the original letters reprinted silkscreen, and contextualised by Schneemann’s restless body, Correspondence Course reveals how an artist can become objectified as a poorly paid twenty-four hour working automaton. CS bemoans this in her letters, the economic struggle of being an artist, as she writes to her friend, the poet Ann Lauterbach, in March 1973: ‘in the city we scramble for jobs – I take any lecture film/discussion I can find,’ which calls to mind Kathy’s emailed concerns following her Australian seduction: ‘… the checks I got in Australia for work all can’t be cashed ’cause they’re non-negotiable and I have ten dollars in the bank, and then and then, oh jetlag, so your message is changing the day – or is it night? – around.’

Time folds in on itself, as the desire for contact amidst the pressures of work, finds pleasure in transnational correspondence. Lucy’s avatar trawls online hook-up sites and sends messages to prospective (detached) lovers as a way of filling up time, and embodying it with desire, however distant. The hotel room is empty but she can still talk to an anonymous ‘someone’, or someones. There is a risk element too that is appealing, escaping the work email and replacing it with sex. An orgasmic collapse.

L: I was thinking about anxiety and work and self-soothing. There is something in there about the breakdown between work and non-work time; about the vigilance that is felt to be required to protect a professional persona, and the psychic toll of that – which of course means that spending time on hook-up sites makes perfect sense. What is masturbation but anxiety, attractive risk and self-soothing? Did you read about those judges who all got disbarred recently for looking at porn on their work computers (but not while they were actually in a trial)? My woman is not working all the time: she is looking for someone to message; she has time to fill and an empty hotel room that might be full of promise. She just needs someone else to activate it.

A band of five working women, operative across print, internet and radio, are performing as themselves in the film’s interviews. They couldn’t be any more in the know of what is at stake when you speak publicly (L). The journalistic interview is used as a model for professionalised conversation, full of skill, the correct body language and performed intimacy, located within public worlds of work and publishing. Such encounters are interrogated as scenes of confession and exposure, but also of artifice and performance, dripping down into the intimate private space of online interlocution. Work and play become confused and become one, as in the letters of Kathy and Carolee and Ann Quin. Their workspace leaks, to give way for the leaky containers of correspondence.

L: Confession, intimacy, shame and visibility are all important in the work. The confessional, the biographic, and particularly the ambiguously fictionalised memoir seem to be having a moment in the work of writers like Chris Kraus, Eleana Ferranti and Karl Ove Knausgaard. There is a question at the heart of the video about the need for desire for contact with another, and also with what that contact might supply you with and how. Online spaces also demonstrate how confession can exist without needing to relate it to a whole person or a whole truth, as a type of rhetoric. This exists against the backdrop of intermingled professional and personal lives. In a way, the pleasure of online sex is that it offers relief that can be compartmentalized, that it does not disturb one’s whole life (except when it does).

Chris Kraus centralises the use(s) and users of correspondence within her work, particularly her first novel I Love Dick, in which she is both character and author. Through Chris’s obsessive love letters to Dick, which are later appropriated as a Sophie Calle-style art piece in the novel (and then turned into the novel we are reading), the author also groups communities of writers and artists together. She’s not only talking to her epistolary affection, but also talking to her friends, fictionalising them through her own work and providing their work with affective critical commentaries. A platform of visibility, however much it is performed. Her life’s texts feed the text we are reading, as she writes:

And I have brilliant friends to talk to (Eileen, Jim and John, Carol, Ann, Yvonne) about writing and ideas but I don’t (will never have?) (this writing is so personal it’s hard to picture it) any other kind of audience. But even so I can’t stop writing for a day – I’m doing it to save my life. These letter’re the first time I’ve ever tried to talk about ideas because I need to, not just to amuse or entertain.

The coursing letter, the immediate email: these epistolary forms of expression offer potential, a space of making contact – friends, as well as sexspace lovers for journalist avatars – through writing and body. Correspondence has cluttered this blog post, made it a space of hysterical chatter. It’s helped me talk to and forge links, between the generations, and in the moment – from correspondent to correspondent. From me to L and M, but also from me to them and on (or back) to Kathy and Carolee: corresponding together and performing the right to speak. To chat together: all girls together, as Kathy Acker once said in a Vogue interview with the Spice Girls in 1997.

‘From Our Own Correspondent’ by Lucy Clout and ‘Blood’ by Marianna Simnett were commissioned as part of the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’. The Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ are a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and Film and Video Umbrella (FVU) in association with CCA: Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow and University of East London, School of Arts and Digital Industries. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.