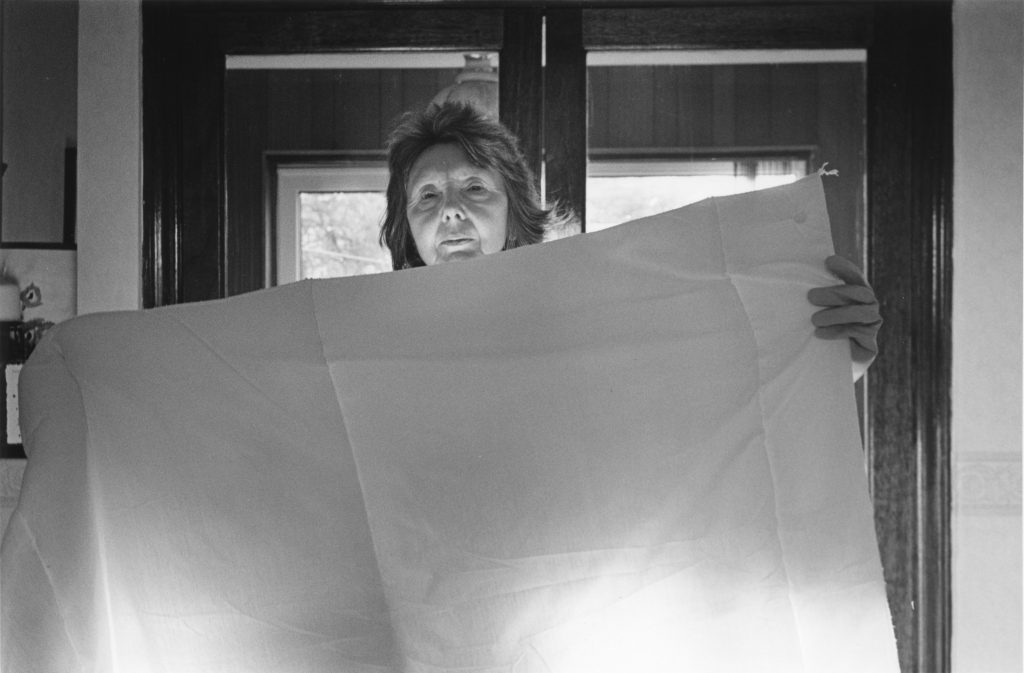

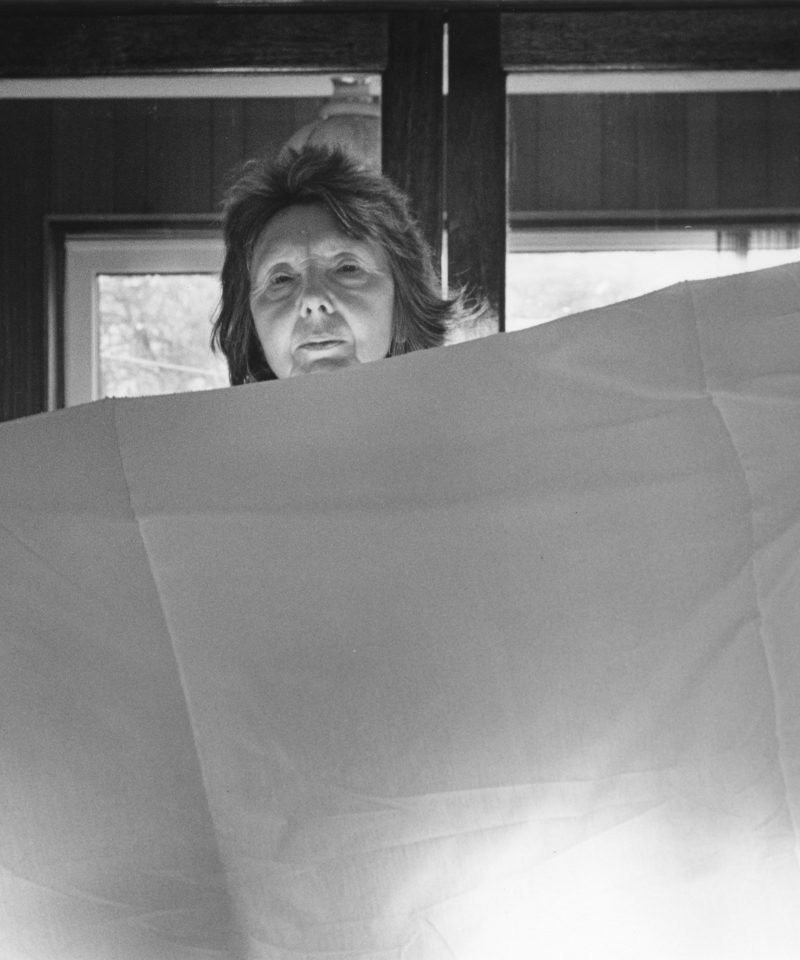

This interview is the last of my blog posts relating to the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2015.* It was conducted over email and edited to develop some of the themes of my first post on ‘Mother’, 1987-present, a long duration series of photos depicting Finn’s mother Jean in the context of the family home they shared until her health, deteriorating since 2014, called for her to move into an assisted living residence.

Lizzie Homersham: I have almost the inverse relationship to my mother, my family home and photography: I lived away from home during my degree, returning to stay with my newly single mum immediately after graduation, aged twenty-three. The home I grew up in was no longer my parents’, or family home; my mum asked my dad to move out in the final year of my studies, when she found out about the latest in a twenty-five-year-long string of denied until they became undeniable affairs. My sister, three years older than me, had left home at the age of eighteen. So it was just my mum and I, driving each other mad with circular conversations regarding my ability to find paid work and move out and her capacity to understand my father. I remember her questioning his yet to be expressed interest in the family photo albums. The atmosphere was suffocating, and tearful until a friend, the photographer Esther Teichmann, whose photography has also captured members of her family, came to the rescue: she invited me to share her flat for an undefined period, at no charge until I got myself on my feet – she knew I’d be better off in London when it came to finding work. I want to ask you how easy or difficult you found sharing a home with your mother, and did the camera play a part in facilitating your relationship?

Matthew Finn: It was easy; my mother protected me from many of the difficult episodes that she had to deal with, especially issues around my father. It was not until his death when I was twenty-one that I began to get an idea of how much of a complex man he was and how much my family had protected me. Or if you look at it another way, how much they kept hidden from me! I was given time and money to experiment with photography even when money was in short supply. I could come and go as I pleased and eventually went off to college but came back most weekends to photograph and get my washing done and have a proper cooked meal. My mother and I were not the type of family to talk about our problems and emotions, except when she was drinking – at that point I could never get a word in. Photography gave me my mother back: the more I photographed her, the more she gave me her time. It helped our relationship in so many ways; in fact memories only occasionally surface as to what family life was like before the project started.

LH: How do the photos that you have taken of your family, especially your mother, compare with any pre-existing photos taken by other people?

MF: Initially they were very similar, partly due to the camera I used, an old Polaroid with the flash bulbs mounted on top. The subject matter also mimicked the family snaps seen in most of the albums of days out with my mother and my aunties and cousins. But once I’d made the decision to concentrate on my mother using the home as a backdrop, then my photos attained a style of their own. I arrived at this decision by looking at photography at art school, spending time looking at the work of other photographers. It was through that period of study that I developed certain formal arrangements and the isolation of my mother within the frame.

LH: Was the final photo of the series included in the exhibition at Jerwood Visual Arts? And did you intend to give a sense of an ending in those photos I guessed might be the last?

MF: The last image I’ve taken is in the show but the series may not yet be complete. It’s a first and a last image in one; the first photo taken in my mother’s new environment of the nursing home also represents the end – the end of our relationship, the end of being able to communicate with one another. I wanted to give the audience a sudden jolt, a real sense of the decline in my mother’s physical appearance. I am happy to include the images that show mental and physical change and maybe it is time to say goodbye.

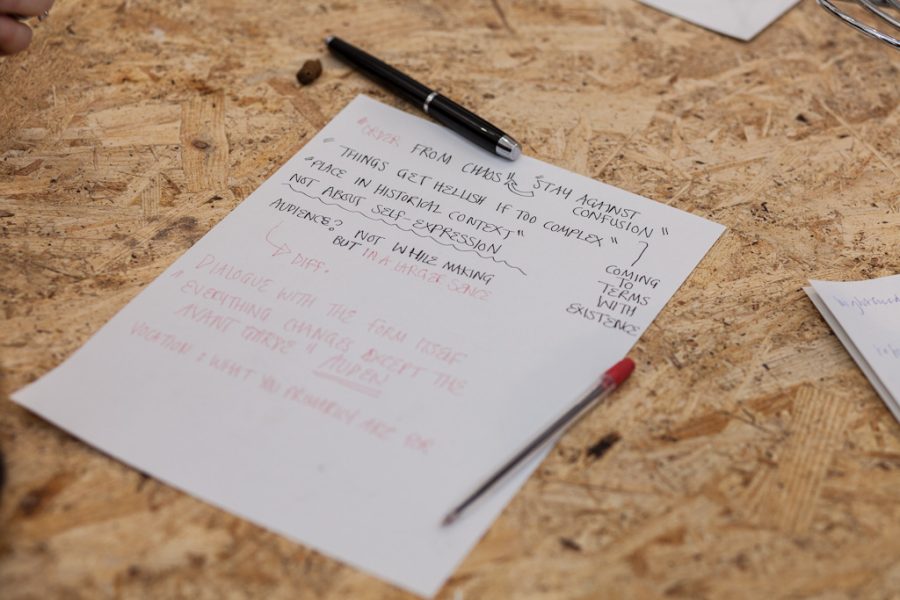

LH: During the talk held at Jerwood on 23 November, you said that dissatisfaction with your work is the thing that keeps you going; you tell yourself the next project will be better. Could you talk about which aspects of ‘Mother’ you feel dissatisfied by, and where you might go next?

MF: I only know that my work is good because I have been told that it is by people who have seen it. But what am I to do from there? Only the maker of the work can find a way to move forward. I’ve never been happy with the images in ‘Mother’ but as I started putting them into order they began to make sense. And the conversation I had with my mother when she was still well, regarding the work that she liked, just had to be enough. For a long time, I didn’t know how to stop but after the death of her brother Des in 2014 and the decline of her health that coincided with his passing, I knew I wasn’t going to be able to improve the series by adding to it. I could see that my mother no longer needed to be photographed; she needed to be looked after. So I started paying her bills, sorting out issues with her home, doing the food shopping and ordering the tablets she was prescribed. The need to find my mother a smaller, ground floor flat to live in had to take precedence over my need to make images. Before the circumstances demanded that I stop, I didn’t know how to, partly because my photography was allowing my mother and I to talk and spend time together. Working on projects of a personal nature can be a godsend insofar as there is no one telling you when they need the work by. The downside is that things can spiral out of control. I knew from an early stage that ‘Mother’ had to be much more than just a few images, and that the series had to be made over a number of years. In the late 1980s, I was looking at other artists who worked over longer periods of time: Nan Goldin, Nicholas Nixon, Emmet Gowin and Bernd and Hilla Becher. I still need to find a voice for my other long-term body of work ‘Uncle’, which involved photographing Des over a twenty-five year period. But my next work will be a yearlong project on rugby players in Hull. I was brought up on rugby league and in some ways it brings me closer to family members who have passed away. I just hope it does only take a year and not another quarter century.

LH: About how many photos did you take in total while working on ‘Mother’, and can you describe how you went about the process of editing the larger body of work for the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2015 show?

MF: I can’t say for certain but looking at the boxes the negatives are housed in, there are about 1,500 rolls of Ilford film, so over 50,000 negatives. Editing is always a difficult and lengthy process. It helped to know which spaces the work would be shown in, and I was assisted by the group of mentors I was assigned as part of the Award. I showed larger edits to these mentors, which was useful as well as complicated because when you show your work to many other people they each have a tendency to take the work down routes that they themselves have an interest in. I took small amounts of advice from all of the mentors and from the staff at Jerwood Visual Arts and Photoworks. The final edit you saw on the wall was a collaboration of ideas, as well as the product of practical decisions made within space and budget restrictions. Interestingly, the more easily read images made the edit, whilst my more complex images involving shadows and surrealism (my personal favourites) did not. In future, I would like to try showing my larger edit, which presently stands at about 200 photos.

LH: I visited your website and have seen other images of your mother in colour. Why exclusively, except for the image featuring a photo on a windowsill, exhibit black and white photography at Jerwood Visual Arts?

MF: Because I hadn’t shown the work before I think I wanted continuity, and the majority of my work is in black and white so it’s also more representative of what I do. The single colour image breaks that continuity, and the continuity of me as the photographer; the picture on the windowsill is one that was taken of my mother many years before I was born.

LH: I’d love to hear more about the ways in which Jean’s awareness of her self-image, which increased the more she was photographed for the series, led to her playing a decisive role in your representation of her.

MF: Once I’d decided only to make images within the home, and on a daily basis, the terms of representation were set. We wanted to make a document rather than construct a character through costume and props in the manner of say Cindy Sherman. The visual material was plentiful, though simply inspired by our daily routines and the objects found in the spaces my mother had put them in over the years. Over time, my mother’s understanding of her image became very apparent. She started to arrange me, telling me where to stand, telling me how close I could go in with the lens and at which angle she was happy to be photographed. In a sense, my mother played the part of director and I was simply the technician pressing the button. When I look back at pictures of my mother from the 1960s it is obvious that she understood how to pose and what to wear. She had many lovely images of herself taken in photographic studios when she was younger, and later she was happy to pose for me in a domestic setting and just be herself.

LH: I wonder whether your anxiety around showing photos of a highly personal nature has been deepened by the prevailing attitudes in the world of photography and photographic discourse?

MF: It has to do with timing I think. I’ve long been asking myself: will the photography world want these images and how will they respond to them? Ten years ago there did not seem to be much appetite for work like mine, especially in photographic discourse. But that has changed as the wider discussions on age and mental health have broken into the mainstream, leading to a better reception of projects like mine. I did show the work to several people about eight years ago and got nothing from the exchange. As a result I kept on making more work but with no real need or desire to show it. I kept it buried. It was only after a conversation with my mother about how we would feel about losing control of the work, if and when it was released, that I realised we were happy to take that risk. I then started showing the work to those I felt would be responsive individuals. They were mainly women: besides my mother, Carol Hudson is a photographer and friend and she offers incredible insights into my work and its possible position within the photographic canon. She is a fierce critic who makes you think about every element of the work. Bridget Coaker from the Guardian offers different insights regarding the photographic market and pays incredible attention to detail in editing. I owe them both a lot and I owe a huge amount to my wife who drives me forward and allows me the time I need to continue working in this medium.

*I will return in March and April to write about the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2016: ‘Borrowed Time’, featuring work by Karen Kramer and Alice May Williams.