In the catalogue essay I wrote last year, for the first phase of the Jerwood/FVU Awards: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ exhibition at Jerwood Space, I penned a series of scrolling epistles to a group of woman writers, most of them friends. (Scroll as in manuscript, and scroll as in blog.) And even when they weren’t friends, like the two Anns – Quin and Rower – I imagined that they could be. Separated by decades, but friends through form, as diaristic expression, forms of correspondence and uncensored syntax recur, and reach out, across the temporalities that divide them.

An early sort of sharing, as in:

FuckYeahFeministArt&Literature.Tumblr.com.

From the Anns’ novels to the blogs of Ariana Reines and Dodie Bellamy, biography is assaulted and sacrificed, to give way for the written performance, as the personal is paradoxically recast as a form of knowingly manipulative masquerade. Performing the confession, in art or online, the woman writer makes herself visible – splurting uncontrollably scaring the patriarchal reader – to then disappear from view in the pixels and fissures of its form.

The original ‘What Will They See of Me?’ text came off the back of a long form essay I had written on Ann Quin’s life and work, through which I had become interested in how confession is performed in writing. A literary style, but also a self-conscious act, it is a strategy closer to the visceral protest of twentieth century feminist art, than mainstream literature or ‘artist-genius’ letter-writing. As these writers expose the body and self – in fragmented, playful, plagiarized fictions – the mode of confession slowly unravels itself as a double bluff, more vengeful than vulnerable. Or naked.

It is no accident that Chris Kraus references Hannah Wilke as a protagonist in this game of publicity, as the author writes of the artist in I Love Dick: ‘[she] started using the impossibility of her life, her artwork, and career as material… As if Hannah Wilke was not brilliantly feeding back her audience’s prejudice and fear, inviting them to join her for a naked lunch.’

But she does not stay naked for long, not in any tactile sense. You cannot see her or touch her, when language returns and fills the gap: embodies but does not violate.

And so soon I realised that it is not exposure at all, it is writing: it is artifice. I called the text Artificial Hearts, culled from Ann Rower’s If You’re A Girl, but a gossipy and gloopy tag line for all. IRL confession pertains to truth, and performance art revels in the show, but I wonder if they’re basically the same thing. In The Buddhist, Dodie Bellamy titles one of her blog posts ‘Heart Publication’, as she performs the self in language, mediated by the contextual surround of the upload: an instantaneous rush of emotion and writing.

Like a love letter in the post. It’s there in the conjunctive: blog-POST: this ephemeral verbal note is to be sent out, worn out and consumed, by not one but many.

I wonder if the blog post is a sort of splurting, or barfing, as described by Dodie in Barf Manifesto: ‘The barf is messy, irregular, but you can feel in your guts that it’s going somewhere, you can’t stop it… you’ve just got to let it run its course.’ In this text, Dodie finds in her friend Eileen Myles’s essay ‘Everyday Barf’ a radical language of bodily upheaval, and in her barf manifesto looks to beckon it in as a feminist literary form. Extending Dodie’s course, I’m interested in how the blog might perform the barf, and how that might aid – loosen up even – the art-critical voice. Writing projectile all over the internet seems more faithful to the 2015 ‘What Will They See of Me?’ works somehow, given the artists’ preoccupations with speech, subjectivity, writing and body.

Like Dodie Bellamy noting the influence of Kathy Acker in The Buddhist:

This is what I was getting at in my post on public display and operatic suffering – an in-your-face owning of one’s vulnerability and fucked-upness to the point of embarrassing and offending tight-asses is a powerful feminist strategy. Writing is tough work, I don’t really see how anyone can really write from a position of weakness. Sometimes I may start out in that position, but the act of commandeering words flips me into a position of power… Like Kathy Acker, I long to quiver and terrify in the same gasp.

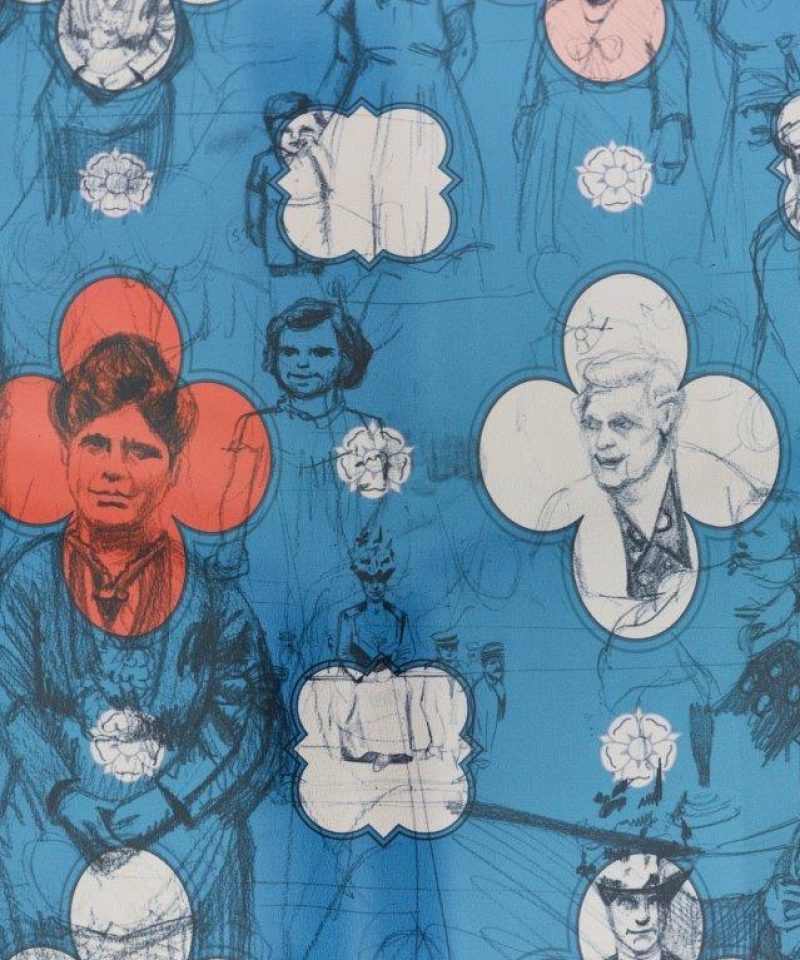

Last Spring, I too was performing feminist influence, fantasising about a community of writers in my text, and writing in parallel to the exhibition’s all female moving-image artists. They were Marianna Simnett, Lucy Clout, Kate Cooper and Anne Haaning, each artist exhibiting a film work in response to the probing desperation of the title: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ Notions of visibility, selfhood, technology and posterity found an outlet in works that were by turns chemical, corporeal, muddy and verbal.

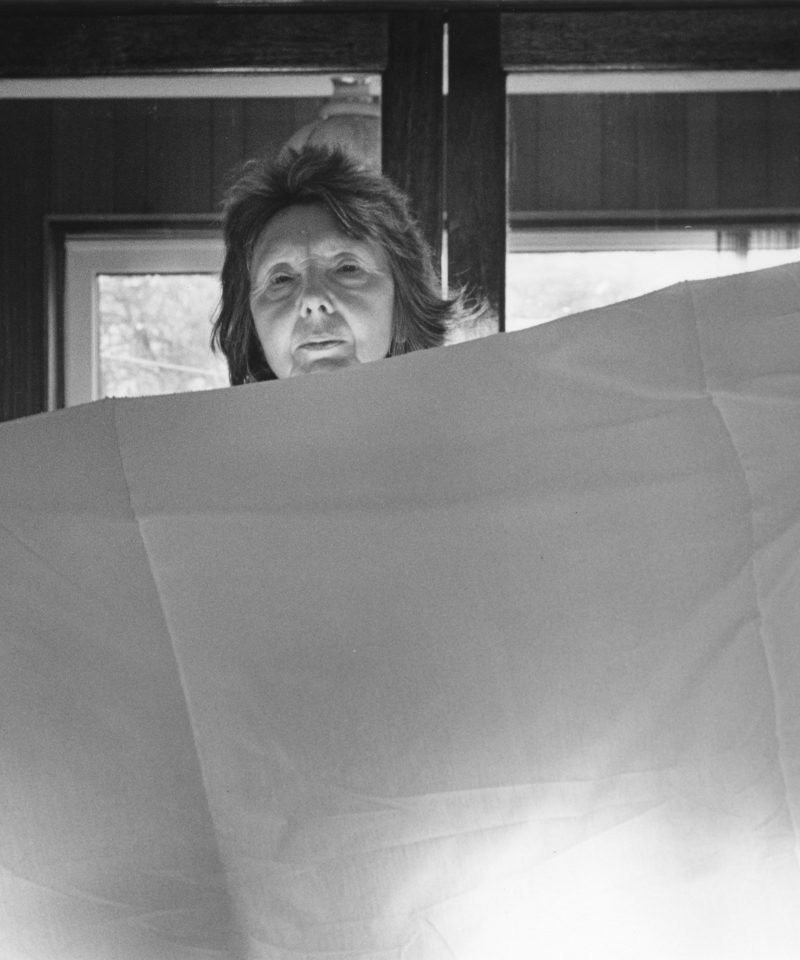

Lucy and Marianna won the awards to make large scale moving image works, which will be exhibited at Jerwood Space from this week until April 26. I snuck a look at the first edit of Marianna’s film, given the curiously pithy title Blood. It tells the abject story of Isabel, the young heroine of Marianna’s previous work The Udder, and the magic realist journey through her own nose. As she suffers with a bleeding and deforming snout, she also finds transformative solace in an Albanian fairytale landscape, as Lali, a ‘sworn virgin’ and committed transgenderist becomes her pre-pubescent spiritual guide. Maternal and paternal. She’s both character and document in this film, as Lali is one of the last of Eastern Europe’s ‘sworn virgins’ to be living out hir life as a man, promising eternal chastity in exchange for patriarchal respect and company. Women Who Become Men, an anthropological study by Antonia Young, is sitting on the gallery’s book-shelf, hinting at Marianna’s own conversations and research.

‘A woman is a sack made to endure,’ Lali – in peasant man-clothes – tells the withering Isabel. By turns sick, sub-conscious, drugged and doe-eyed, Marianna presents the young girl positioned on a fragile bridge between vulnerability/femininity and freedom/androgyny. Located in an alternate interior world, I wonder if Marianna is proposing an allegorical tale of transgression, fusing young girl ‘LOL’ speak with genuine curiosity about gendered subjectivity. The climactic final sequence involving a stream of leaking (crêpe-paper) blood from an oversized (papier-mâché) nose seems less gruesome end, more hopeful beginning.

Lucy will be showing From Our Own Correspondent, which takes its title from a tabloid trend for claiming false authorship for an article, when in fact it has been brought in from outside sources. Lucy zooms in on how contemporary news and gossip is presented and consumed through a series of interviews with the media professionals and bloggers that comprise this round-the-clock industry. The stageyness of the set-up is revealed by Lucy’s behind-the-camera request to remove a snotty tissue from the shiny side-table, communicated through a flash of red subtitles. It is a work that performs its subject (like I am looking to do also), with the exchanges set in a number of anonymously mahogany skyline hotel rooms.

The stills from the film show a blogging avatar, surrounded by plasma television, leather headboard and all sorts of beige furnishings. She is connected to the plastic, a coded being, wired to deadlines and breaking news. It is a warped environment of work and intimacy, a space of material and immaterial labour. Writing and talking. Probably tweeting. With a flimsy wall between public and private, the hotel room signifies how within this mode of work, the personal is always leaking (like Isabel’s blood) into the professional, also shown in the desiring pop-up messages that flash upon the screen and the avatar’s night-time monologue. Correspondence (for these correspondents) is work and play, continuing Lucy’s forensic interest into the contemporary mechanics of everyday speech that characterised her first ‘What Will They See of Me?’ work, The Extra’s Ever-Moving Lips.

Splurting, barfing, leaking.

No walls. No censors.

The blog performs the un-edit, the un-collected: shame-free. It makes me think of a recent post by Sara Ahmed (whom Lucy also retweeted in August), on her site Feminist Killjoys, which performs the ephemeral as an antidote to the time-heavy academic paper:

So emotional; so moved by being heard as emotional. You are used to this. Eyes rolling. You are used to this. Feminists are heard as being emotional whatever they say, which is to say, again, independently of what they say. Being called “emotional” is a form of dismissal. How emotional. Just look at you.

A container, a leaky container.

Be careful: we leak

Objects of correspondence as leaky containers, filled in with the hand of the interviewer, letter-writer, emailer, tweeter, blogger. These are positions of writing engaged with speech as ephemeral and moving, sneaking to the fore from the visceral, messy margins.

In more ways than one.

Onomatopoeic discharge.

With a sender and receiver, it is a relationship of embodiment. Always two parts or more, whether real or imagined.

There’s freedom in the spill.

The blog leaks: it relocates emotion from private to public, like Lauren Berlant’s ‘intimate publics’, as she writes in The Female Complaint: ‘The personal is the general. Publics presume intimacy.’ An intimate public is a ‘space of mediation’, and performance, whereby the personal is processed and churned over through everyday experience and objects, ready for consumption. As a ‘porous, affective scene of identification among strangers’, the blog seems to fit the consolatory promise of the intimate public.

I’m going from essay-writer to blog-writer, as the Spring Jerwood Visual Arts’ Writer in Residence. I wonder what will happen in that role-change. Will I write quicker? Will I pour my heart out? Will I pull a scroll from my vagina and read from it like Carolee Schneeman? Will I let them see me? What will they see of me?

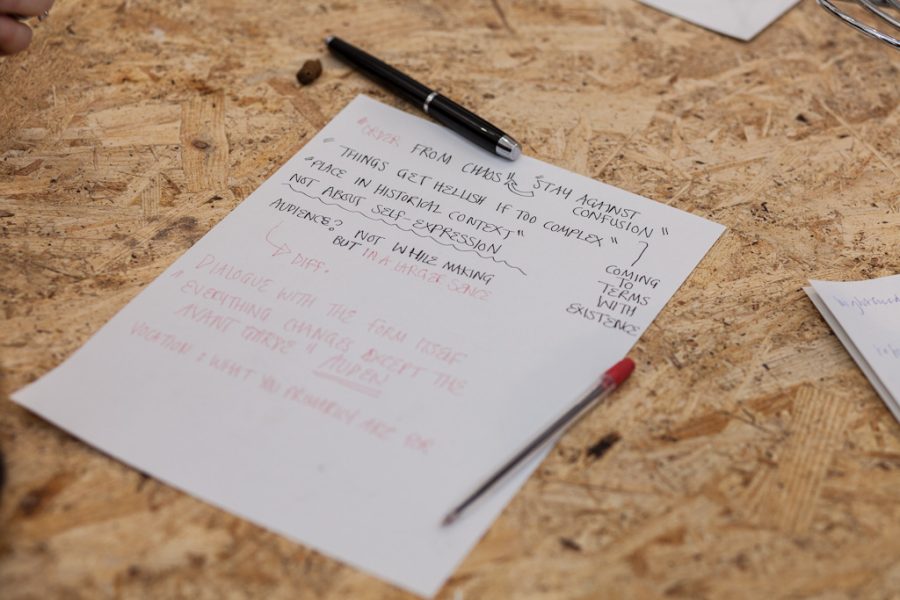

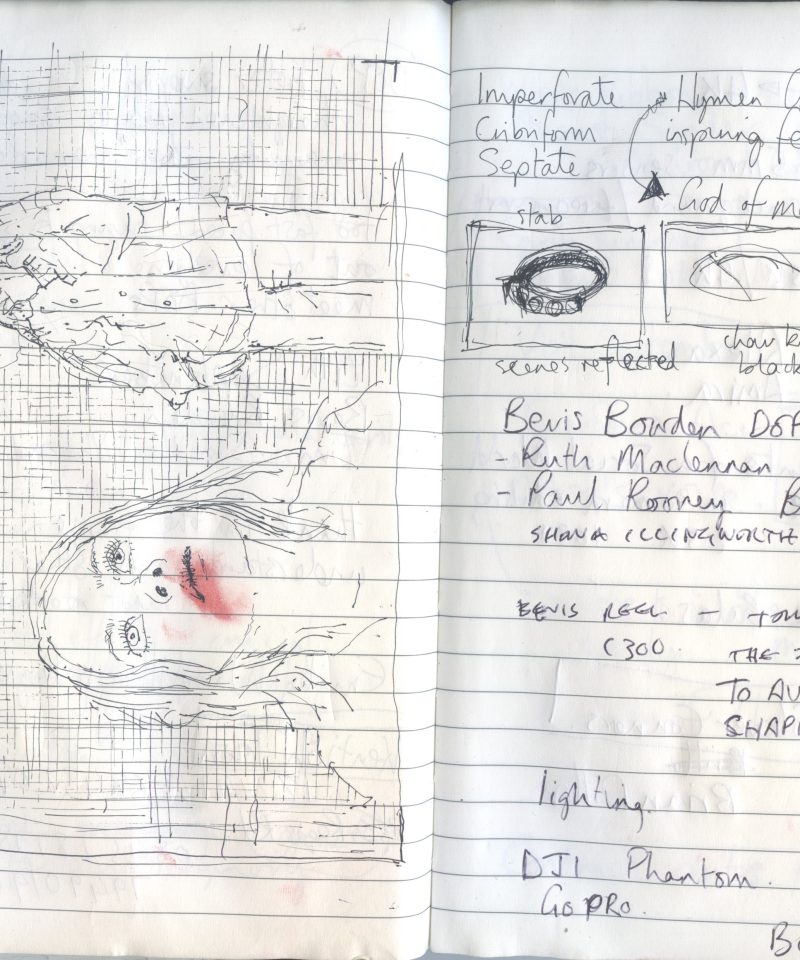

In Artificial Hearts, I ended with discussions of Dodie Bellamy’s The Buddhist, and Kate Zambreno’s Heroines, both books made from dead blogs. Edited, reframed: cleaned up. I am interested in resurrecting the form, along with other forms of correspondence, such as letter, email and diary, as a method of art criticism. I’m going to start a diary for the first time in my life (bad writer) and see what happens; see what can be pulped from this pool of bodily, immediate language. I will take it with me to the gallery and write notes in residence, in public, as that will be more intimate.

I realise this is all a bit self-referential, a blog post about blog posts, but I am wondering how I might harness this form of digital writing, and how it might offer potential for women’s writing and women’s writing about art, and women’s art practice. Tumblr was founded in 2007, providing infinite publishing platforms for all genders and sexualities, in a form inherently infinite. I am interesting in performing that initial promise, using the blog post as a way of writing through art, and getting closer to it.

And I will write letters to Lucy and Marianna, to them and to their work. I will look to build an intimate archive: a space of performance that writes art and body in ephemeral literary objects. As when José Muñoz wrote in ‘Ephemera as Evidence’: ‘Ephemera, as I am using it here, is linked to alternate modes of textuality and narrativity like memory and performance’; it is the ‘glimmers, residues and specks of things.’ Ephemera will be used not as information, but as embodiment: a way of writing through the art object. A(rt)-(o)BJECT. This is to be an abject as well as an intimate archive. The blog or digital epistle is a private textual object, mediated through the act of writing and the public screen. It speaks. It barfs. It leaks.

The Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ are a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and Film and Video Umbrella (FVU) in association with CCA: Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow and University of East London, School of Arts and Digital Industries. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.