I remember playing in washing, a romantic memory of the feel of warm sun and the smell of cleanliness mixed with a hint of the not-allowed (to dirty the clean sheets would have been trouble). Standing between lines of towels, pants, trousers and T-shirts is like occupying a place between the layers of acetates that make up a cartoon image. When too dry washing becomes crisp and flat like a paper cut-out. Inhabiting this space I had a sense of what the characters made for my theatre must have felt like when shunted back and forth between layers of a cardboard stage-set. The theatre was called The Royal Theatre. An adult had tried to persuade me that The Theatre Royal was more fitting but this backwards syntax made no sense to me at the age of six.

Surely one of the most-often taken tourist photographs of Venice is one of laundry strung precariously above canals. It gets me every time. The intimate, the familial, hung out across grand, historic vistas interrupting the stasis of set architecture. This laundry evokes personal resistance in a place that is slowly crumbling, a sense that by living and making Venice present its inhabitants might halt the city’s inevitable sinking-sliding.

The two-way nature of those lines, strung up between buildings, makes me wonder if people have washing line wars. The to and fro nature of the thing: does it provoke the kind of neighbourly anger that I have seen result from parking on suburban British streets? Or do people peacefully share lines- one day each perhaps, or one half per flat? Is it possible to feel that kind of petty rage in a place as beautiful and romantic as Venice, or can anywhere feel humdrum once you’ve been there long enough?

Perhaps it is this sense of mundanity that modernist architects wanted to avoid when designing their monolith towers of steel, concrete and glass. Hanging such untidy things on the balconies of minimal tower blocks feels heretic, rebellious. To see these garments necessitates an acknowledgment of the individual lives taking place within, of their irregular rhythms and tastes. I enjoy the fragility conjured; the flapping shirt that might fly from its perch high on the side of a building is as precarious as the sock that might plop into the Venetian canal, its owner only noticing its absence much later, when looking for a pair.

Architects might also have been aware that washing on balconies draws attention to inhabitants’ lack of private outdoor space, offering ammunition to the British objection to modernism that comes from a conservative love of boundaries and privacy: ‘but what about a garden?’. And perhaps class is an issue here too. I’m thinking of the intro to Coronation Street: the camera pans down, from a skyline of tower blocks to the more intimate scale of terraced housing, across roofs and onto a yard where a ginger cat picks its way between two washing lines. Does the laundry here in small brick yards highlight the working class yet independent nature of the neighbourhood?

However old fashioned this may seem, perhaps the idea that people are doing their own washing, not outsourcing the work to a maid or using dry-cleaning services, demonstrates a lack of financial resources. Before the widespread ownership of the washing machine in Britain, doing the laundry was a day’s work. Most people in the UK now have a washing machine, meaning that laundrettes are generally places for those in transitory situations or those with very little. Is the washing line, as a public trace of domestic labour, uncomfortable for some people?

Drying washing inside feels sad, cloth lying limp on radiators or huddled around gas fires. When no outdoor space or too much rain make hanging out impossible an endless damp smell pervades, of things that never quite dried. And then there’s the danger of nylons near heat… Here’s to the flapping of clean sheets like sails on a ship. Here’s to the loss of garments from tall hoists above water and motorways. Here’s to the intimacy of showing your smalls in and on public piazzas, yards and balconies.

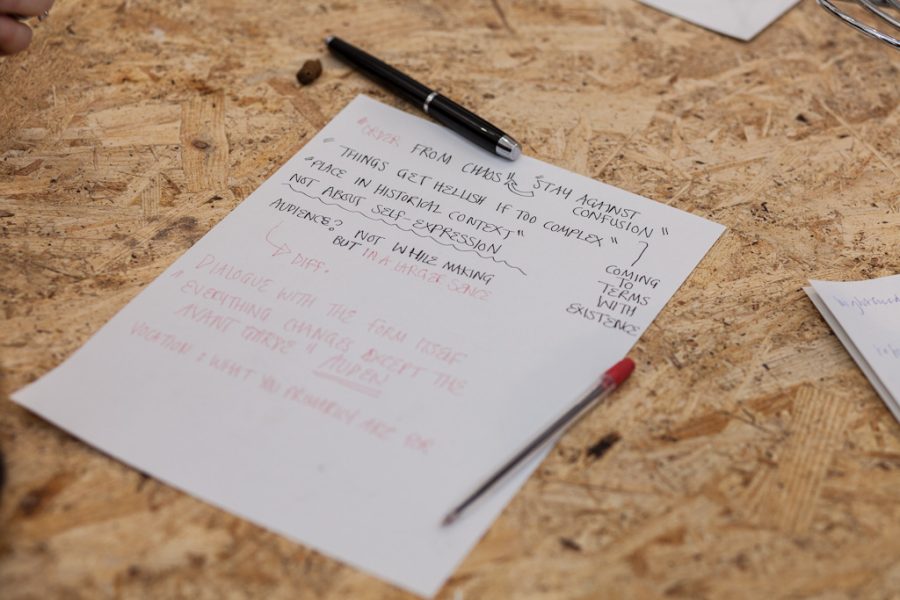

These notes come, in part, from a conversation with Paul Schneider on the opening of his show ‘Hanging Out To Dry’ at Jerwood Visual Arts’ Project Space.