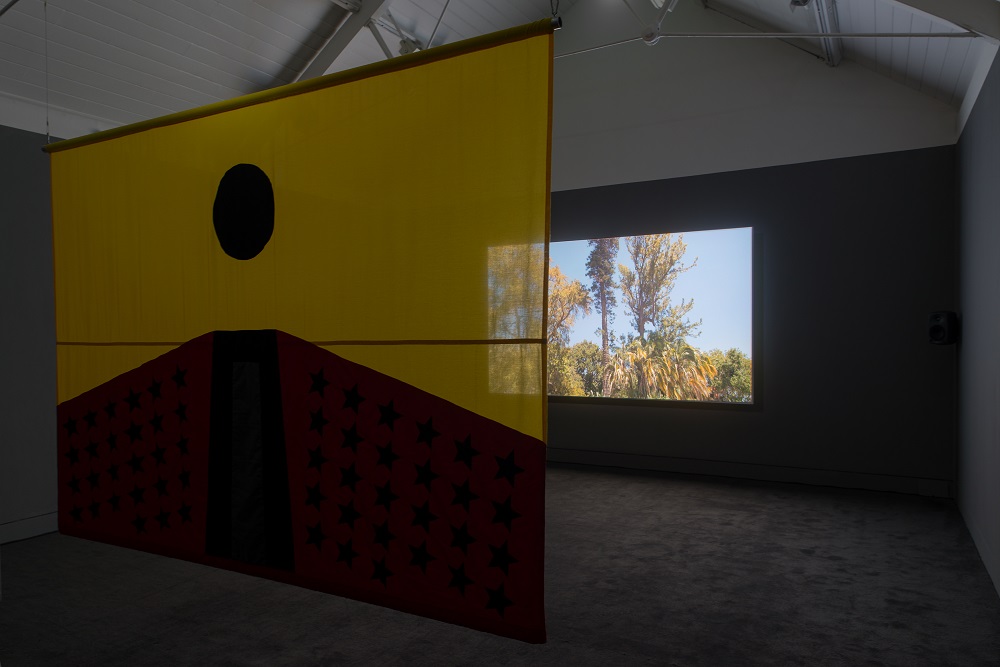

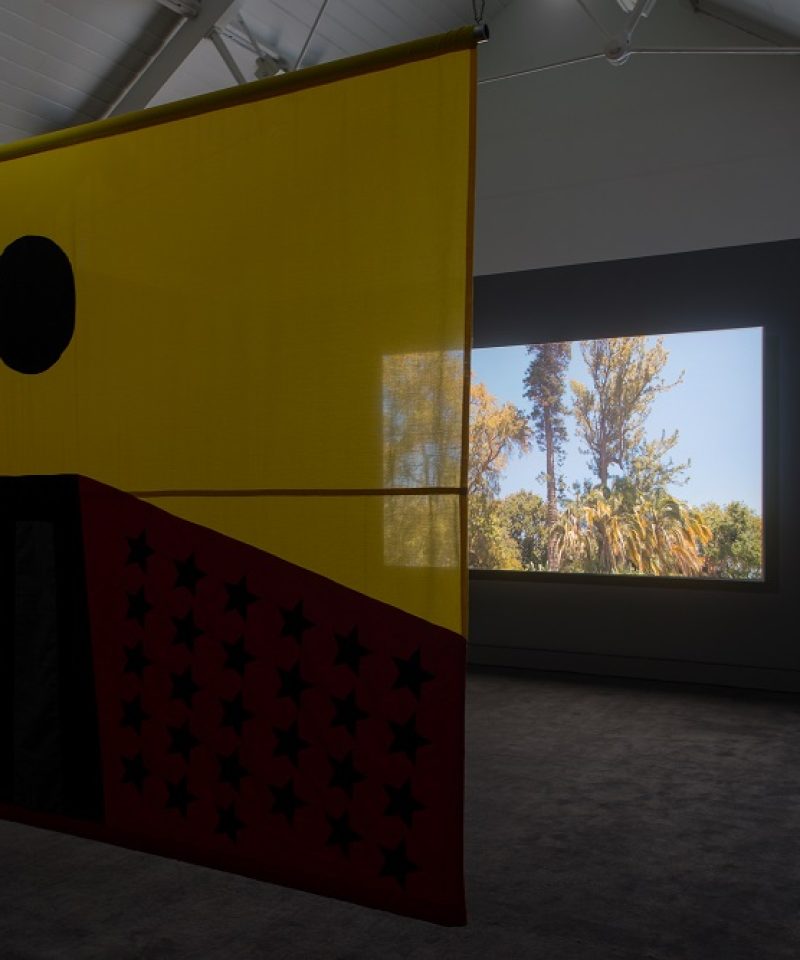

From his wider, ongoing Afrofuturist Relic Traveller project, Larry Achiampong presents Testimony for the Relic Travellers’ Alliance (2017), a mixed media installation comprising his film Relic 0 (2017) and the Pan African Flag for the Relic Traveller’s Alliance (2017), as his contribution to 3-Phase. Within Jerwood Space, Achiampong’s flag hangs in front of Relic 0, forming a semi-permeable barrier between the viewer and the work, imposing its presence immediately and forcing them to navigate around it to view the film behind. In a similarly bold, yet much more public move, the flag also sits atop Somerset House, where it has been installed since July 2017. Built in the neo-classical style, with a storied history that includes the (likely false) legend that Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson once worked in the building, Somerset House is a prominent symbol of imperial Britain, and as such, Achiampong’s symbol of an utopian Afro-centric future becomes a powerful gesture, puncturing the building’s neo-classical pomposity and imperial notions of Britishness.

By planting his flag atop the Somerset House roof, Achiampong claims the future for Africa and his vision of the African Union. At a time when Britain is removing itself from the European Union, closing itself off from its neighbours, and while far-right political ideology continues to gain ground and influence popular opinion in the UK, USA and across Europe, it becomes increasingly plausible to consider that any utopian future may lie elsewhere. This is what the world of the Relic Traveller proposes, at an undefined point in the future, a prosperous African Union – operating under Achiampong’s banner – ensure that they learn the lessons of the past, such as how to better govern than nations such as the UK, ensuring a continuing prosperous future. This is done via the ‘Relic Traveller’ programme, whereby the Travellers secure testimony on their experiences from across the African diaspora, which include the turmoil that they have lived through.

Turmoil is a word that frequently comes up in conversation with Achiampong, whether discussing the plot of the Relic Traveller film instalments, or the red sections within the flag’s design, prominently representing the turmoil experienced by Africans and those of African descent. It is clear that to Achiampong, turmoil is a fundamental part of Black life, part of the legacy of slavery and colonialism that continues to be felt today. The female narrator of Relic 0 expands on this, discussing the idea of globalisation and how the story we were told is that, through global cooperation, we could end inequality across the world. But in practice, it was a neoliberal, Western idea of more efficiently exploiting global resources, ‘depend[ing] on the plight of others to prosper’, as the narrator puts it.

As these words are delivered, the camera cuts to show a bell. This, it turns out, is the slave bell, used to punctuate the day in Company’s Garden, Cape town, South Africa, a pleasure garden for the use of the British and Dutch East India Companies that, of course, was built and run on slave labour. The image is a powerful reminder of the brutality of colonial regimes. The narrator’s words remind us that while society has evolved significantly since the days of the slave trade, Western wealth and prosperity is still largely supported by the exploitation of cheap global labour and structural inequalities continue to exist as a legacy of the slave trade.

A recurring idea throughout the project is that current Western societal structures simply aren’t built to accommodate Black people. The scathing line that the narrator in Relic 0 parrots – that ‘change takes time’, that people should not riot, should not question, and should instead passively and politely wait for meaningful change to occur, illustrates a status-quo preserving, stalling tactic . This is expanded on in Relic 1, where a new female narrator explicitly states that the societal system was ‘not built for us to exist unscathed’, and that success within this system made a person virtuous. Thus, the assumption made is that anyone struggling is inferior, reinforcing the neoliberal lie that the world is a level playing field and that we all share equal chance of success if we just work hard enough.

The Relic Travellers themselves become heroic figures acting to prevent this kind of society from resurfacing within Achiampong’s African Union. The costume design references this idea , as what appears like an astronaut’s helmet is paired with a military-green flight suit, lending the wearer an appearance of something between an astronaut and a test pilot, harking back to mid-20th century American heroic iconography. The Travellers, the costume implies, are heroic explorers, flirting with danger in order to pursue societal benefit. The image of the discarded helmet on a grassy floor becomes a motif of the series as it is repeated through Relic 0 and 1. In 0, this is all we see of the Traveller themselves, an enigmatic tease for what future instalments will show and demonstrative of Achiampong’s patient method of world-building.

Throughout Relic 0 and 1, Achiampong is willing to provide the audience with just enough to want more, to show enough of the detail to hint at the shape of this future, but still leaving the audience enough space to fill in the blanks for themselves. It isn’t entirely clear what state the world of Achiampong’s future vision is in. It seems that while we are informed about the utopian successes of the African Union, the rest of the world may not be sharing this success. The Relic Travellers seem to visit lands outside of time and society, dead places with no trace of human presence, that seem ancient and modern, such as the concrete structures in Relic 1. This is a world that begs to be explored further, and to see Achiampong continue to fill in the details will be an exciting journey to follow.