Elinor Morgan: It seems like your work is a meeting of categories of making and materials as well as locations and cultures.

Jasleen Kaur: I’ve never thought of it in that way but I do think of myself as a cobbler. I pull together unlearned and culturally acquired knowledge in my work. When I was training as a jeweller at the Glasgow School of Art I had quite a particular way of making; I’m not very precise. I was brought up in a very religious Sikh family in Glasgow and although my work is not hugely autobiographical it is about meeting points.

EM: Does this work represent that cobbling nature?

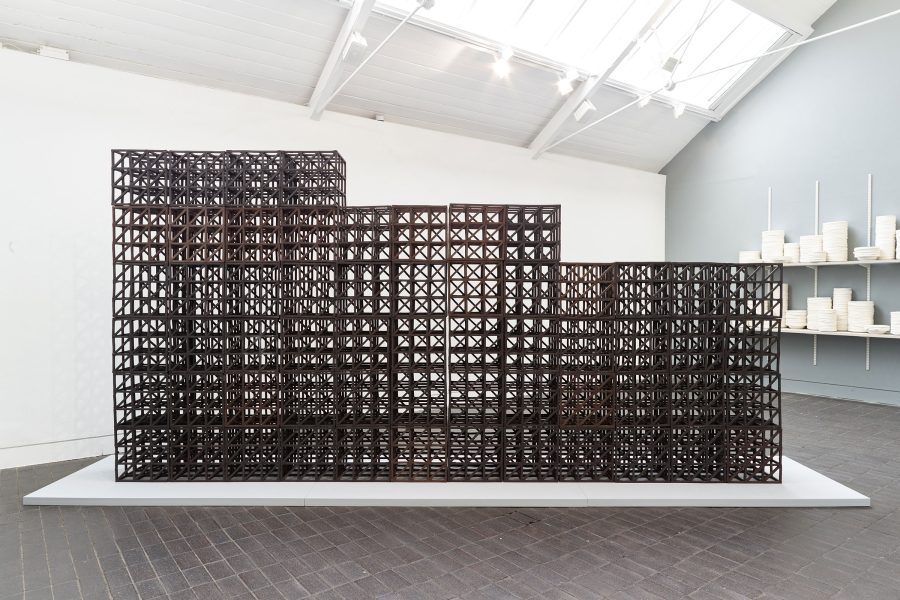

JK: My dad owns a hardware shop and I use a lot of found objects. The work I have made for the Jerwood Makers Open came from those marbled buckets you get outside hardware shops. I wanted to take the revered material of marble and shift it into a less valuable material. The people depicted shift too, from being Lords or Gods, those traditionally shown in Western portrait busts and Indian religious sculptures, to being three men or women.

EM: But they aren’t women…

JK: No, but I don’t see that as important, especially because I hope the project isn’t finished so I may add women in. There’s a very specific reason why I chose to show these three men. First first is my great granddad who moved from Punjab to Glasgow in the 1950s, the first in my family to come and make that cultural shift. When he left the Punjab he had a Turban and a beard and in the few photos we have of him in his early days in the UK he wears a flat cap and a moustache. He was keen to assimilate and because he didn’t have a community around him until later. He was a key member of the Sikh community in Glasgow; he used to borrow Bollywood films from his friends in Leicester to play in the cinema after temple on Sunday.

Then Edward Said is in the middle. When I came across his writing at the Glasgow School of Art it gave me a real sense of place as a practitioner. I realised that people were writing about the ideas that I was thinking about and making about. The last is Lord Robert Napier. His great grandfather fought in two Anglo-Sikh wars in the time of the British Raj and there’s a big statue of him outside of the Royal College of Art. The history of British-Indian relations is so complex and so fascinating.

I contacted the current Lord Robert Napier when I was studying at the RCA. I wanted to tie a turban on his head as a visual marker of where we are now. He said yes, so I took my dad as the turban tier to Wiltshire and we made a portrait. It feels like the three busts represent a starting point, a mid-point – or sense of place – and a sense of how I am working as an artist now to shape the dialogue.

EM: Busts like this might normally be made from marble. Here they are made from marbled plastic. Beyond this pun, why did you decide to make bust portraits in this rather Western, classical style?

JK: I am very interested in the typologies of sculpture and it’s role. In the European tradition, to make a marble bust is to revere someone through a laborious material process to the point where the material inhabits its own monumental sphere and cannot be touched. I have been thinking about equivalents in Indian sculpture, which depicts Gods and Goddesses and Buddha in this way.

People bathe them in milk and feed them fruits and in some situations people even put them to bed at night and wake them up in the morning. This humanises the statues by making them functioning objects in daily routines. The busts I have made signify meeting points between these opposing traditions and, of course, they play with the marble/plastic materials.

EM: You applied to the Jerwood Makers Open; do you think of yourself as a maker?

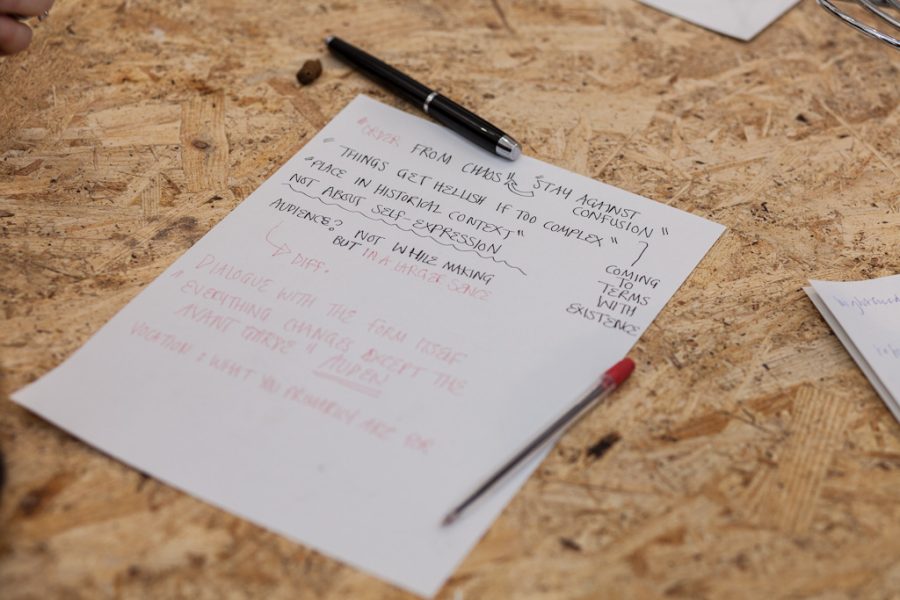

JK: I make things that can operate in a number of contexts. For the piece ‘Chai Tea Stall’, in 2010, for example, I made a travelling tea stall with small clay cups. In the gallery it was an artwork by Jasleen the artist, but in a community centre or family home it was just Jasleen making tea. If something functions in a number of contexts then I think it works. That’s a litmus test for me. I am not interested in hierarchies between art and craft or maker and artist. For me it’s about the maker’s intentions. To do something artfully is to give it time and care.

EM: What have you gained from your involvement in the Makers Open?

JK: It has been different for each of the five of us. I applied to shift my practice away from relying on found objects, so that while my work would still be informed by the qualities of found objects I would have more independence and agency. It’s been a chance to produce something in completely different materials with a completely different aesthetic because the project took me out of a comfort zone.