Thanks to @matthewjmclean and @LizzieHom for (inadvertently, I’m sure) embroiling themselves in a mercifully brief but entertainingly awkward Twitter exchange with the author of these blog posts several days ago. I’m glad it happened, though: Matthew kindly recommended a number of recent articles that might otherwise have escaped my (inattentive, at times) attention. I’ll be drawing on some of those texts and images in the following post. And continuing in the open, generous spirit of ‘stealing other people’s research’, I’ll also be discussing a wonderful, and wonderfully understated, short film by Yvonne Rainer suggested to me by Kate Morrell following our recent email exchange.

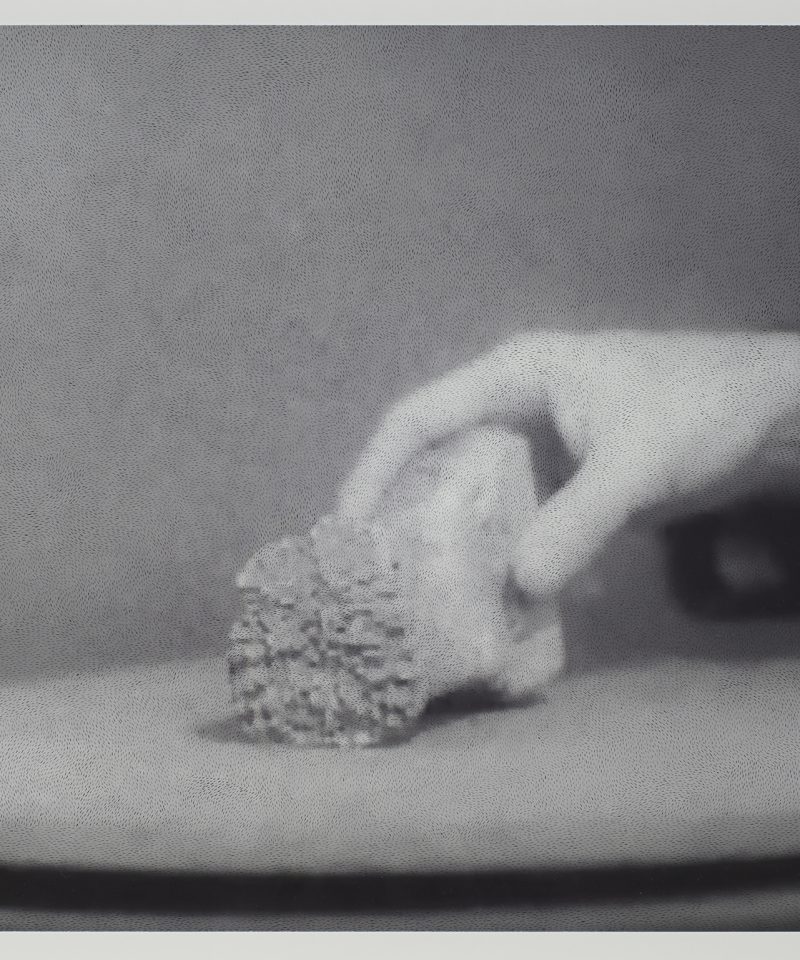

I was excited (and a little humbled) to encounter Kerry Doran and Lizzie Homersham’s excellent piece Digital Handwork in Rhizome, published several months prior my post, unbeknownst to myself, in which the authors explore the various manifestations of hands in digital art: labouring hands, sensory hands, human connections. Although my ignorance of their text no doubt demonstrates the fact that it’s always good practice to Google your subject prior to going public with an article, I consider this blog an unfolding project – I think I said so at the start – and, actually, it’s as cogent and wide-ranging an essay as one could hope for: ‘In all cases,’ the authors argue, ‘hands act upon viewers, detached from bodies yet still enacting desire.’ The piece demonstrates how the advent of digital networks, augmented realities and technological bodies (engaged in labour or leisure, performance or play) have not rendered biological hands – already a familiar art-historical motif – an anachronism. These appendages have, in fact, permeated the ‘framing of human life by digital technologies, as well as the shaping and subversion of these technologies by humans.’ Humans, yes… But also, for our purposes, bears.

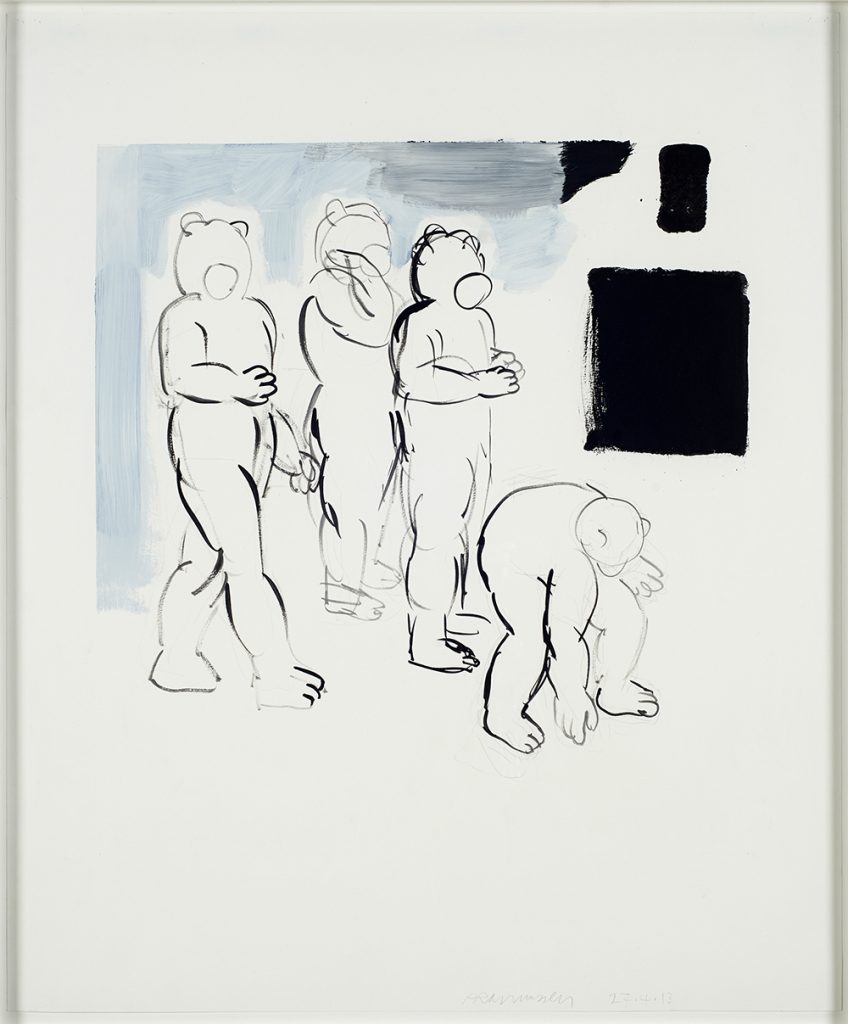

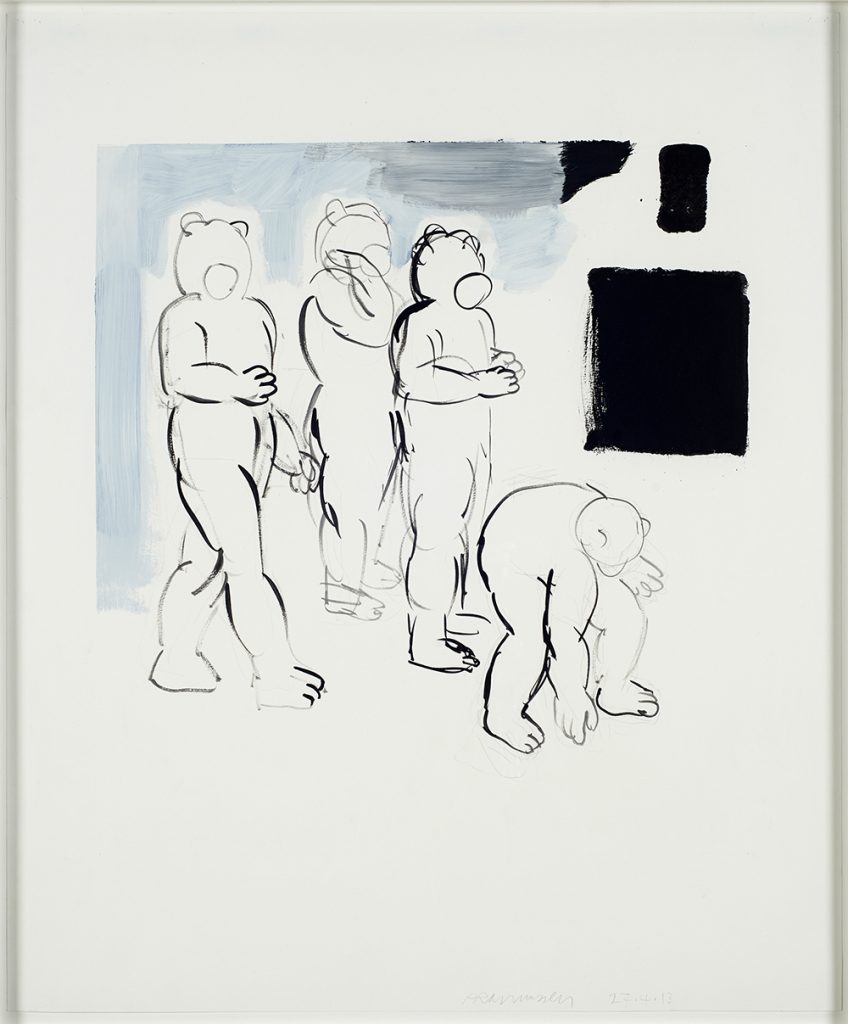

Peter Ole Rasmussen’s work in the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014 is the self-explanatorily titled ‘4 Bears, 3 Standing, One Bending Down’. The ambiguity of the image – the slightly sinister aura of a clandestine congregation of muscular animal-men; the eyeless, inscrutable faces, one of which appears to have just this moment apprehended the viewer; the suggestion of stalled movement, of creatures paused in a journey east; the quivering outlines, the sketchily drawn and re-drawn lines – make the piece, for me, among the most intriguing in the exhibition. Some of the other drawings in the show – the works by Gary Edwards and Jonathan Huxley in particular – emphasise the gravity of carbon; the paper’s receptive surface warped beneath repeated applications of lead, the steady pressure of the artist’s hand. Rasmussen’s work in oil, by contrast, offers a more provisional vocabulary of gestures and marks, one which naturally extends to his depictions of (four-fingered) hands.

It would be hard to imagine these cartoonish hands fondling smart-screens to upload selfies or fling revengeful birds across cartoon terrains. Yet the ‘inaccuracy’ of Rasmussen’s bears’ hands, their protruding, balloonish chubbiness, points towards an obvious rift between the physical hand and the surface image, the digit and the digital. Fundamental to the development of Apple’s first ‘multi-touch glass display’ – the tactile screen that to a large extent defines the operation of iPhones and iPads – during the early 2000s was an acceptance of the fact that fingers are, by computational standards, massively inaccurate, and that any technology premised upon the encounter of fingertip and computer chip would need to be built from scratch (partly, one assumes, to secure a new patent on any such technology, and thus greater market share). Who wanted a stylus? Not Steve Jobs, for one – he could not countenance that fiddly mini-pen. Retiring the stylus was an elegant and necessary design choice, to be sure, but it presented Apple with a problem. Rather than modify an existing hard- and software, a whole new operating system had to be written; one built around the fact that fingers, in relation to pixels, are fat. On this point Jobs may have been inspired, but probably wasn’t, by the episode of The Simpsons in which Homer gains weight in order to work from home.

Homer Simpson’s fatness, like his low IQ, is a running joke. By conventional Western liberal standards, he is a ‘bad father’ – stupid, capricious, lazy, self-involved; a neglectful protector and scatterbrained disciplinarian – and therein lies his satiric potential. The fact that he’s a cartoon and not a real person means that his excessive corpulence to be exaggerated for grotesque effect, milked for parody: the ‘inaccuracy’ of his representation (yellow skin, bulging eyes) makes him, counterintuitively, a perfect vehicle for exacting observation.

I first saw Rasmussen’s drawing at the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014 private view, a matter of days after attending the private view for Paul McCarthy’s current show at Hauser and Wirth. McCarthy himself was there – haggard of beard, wicked of grin, but sporting a beautiful pair of spectacles, he resembled a gin-swigging uncle made good – in a hot room thronged with the requisite quota of perma-tanned millionaires, chatting with the (immaculately attired, to my mind) curator H.U.O., and although I was not close enough to eavesdrop it was clear from his (Obrist’s) genuflecting body language that the work was being lavishly praised. Among the lurid paintings on display was one memorable piece in which a skinny nude woman with vivid, wound-red nipples and oversized head could be observed squirting a long brown streak of liquid faeces onto the eyeless, open-mouthed supplicant below, while, elsewhere in the image, yet more pink and eyeless creatures gave and received fellatio – for all its apparent dynamism, it was a strangely numb-seeming debauch.

McCarthy’s new works were vaguely fun in a deviant, Johnny Ryan-ish way, but they were not shocking; and without the shock, there was little interest. And so, as we finished the final millilitres of our complimentary beers (Becks, the labels loosening off the bottle with condensation), we moved into the final room, which was filled with drawings.

If McCarthy’s paintings presented the ‘headline act’ in all its predictable fullness – an excess that you predicted prior to seeing the works on show; an excess that fails because it fails to exceed your anticipation of it – then the drawings possessed a virtual quality inherent to the medium of the sketch: a form which by its nature is unable to produce a ‘finished’ work. Instead of the paintings’ wisecracks and punchlines, these drawings – messy, gestural, seemingly the product of a minutes-long tantrum – were less resolved, and thus more openly suggestive. The best of these works did not present pornography as pornography (McCarthy-the-painter’s modus operandi, it would appear) but hinted towards the grim rituals by which the body is rendered object, and abject, without asserting such contexts blatantly. Hands and other body parts were caught in tangled webs of scrawling lines, carbon swirls of malignant energy.

McCarthy’s pencil-drawn hands, like Rasmussen’s pencil-and-oil ones, have a sketchy quality that invites multiple readings. The subjects and subtexts that these artists explore are clearly worlds apart, but share a resemblance in terms of technique. Indeed, the best drawing in the McCarthy show – a drawing which I did not take a photo of, have been unable to track down online, and therefore cannot present here – contains a number of bear-like creatures huddled, if I remember, in a sinister group. In the absence of that particular piece, here (and above) is Mad House Drawing 3, a work from 2011 that wasn’t actually in the show. But it gives a general idea.

Conceptually and visually, sketches have an open texture that leaves them open to dismissal – vulnerable to those who disregard ‘incomplete’ work; who like to see the labour on the page. It is equally possible to fetishise the sketch, its perpetual deferral of finality, its teasing refusal to close the circle. It’s only once you get up close to Rasmussen’s work that you notice that the darker, more immediate lines, rendered in black oil, are secondary to the delicate underlying pencil. The ‘double vision’ effect draws attention to the relative importance of pencil and oil in the hierarchy of artists’ materials. The pencil marks are swifter, lighter, less consequential. The ink retains a sense of quickness, but is certainly more considered, more final. Artists’ hands always speak through prosthetic extensions, tools which have social histories; tools which in turn create a sense of motion in the hand, the foot –

– and the head.

(I never got round to the Rainer film. I’ll save it for next time.)