For my penultimate post as the Jerwood writer in residence I have written a series of short reflections on the Family Politics exhibition. Later this week I will upload my final posting, a collaborative text with Joanna Piotrowska.

1) My dad was a keen amateur photographer, he commandeered the bathroom as a dark room. I remember days out with a Nikon SLR strapped to his arm. He would dress my brother and myself in our best clothes – near identical but with slight variations, bomber jackets or shell suits (or whatever was fashionable at the time). He would often have us pose in front of local landmarks. My mum would be in the middle and my brother and myself to either side, symmetrical and centred in the frame – staring back at the camera. Pierre Bourdieu would call this a request for ‘reciprocal reverence’ – the subject facing towards the camera is a call for recognition from the spectator. Staring at the camera, the three of us would say sausages or cheese, and sometimes both. When I look back at these photographs I’m never quite sure what I’m looking at; myself in the past tense, or my younger self peering into the future. Most of an audience for an image aren’t born yet – early photographic discourse focused on the idea that the photograph would outlive its subject. It seems this anxiety was translated into the linguistic system around it, in the catalogue for the group exhibition Anxiety of Photography, Matthew Thompson writes that photography has always been absorbed in the rhetoric of aggression “We shoot frames, and bombard the world with images”. It seems anomalous to pair paternalistic care, formalised through family photography with the language of war. Maybe it is the disjunctive quality between aggression and affection that returns us to these images over and over?

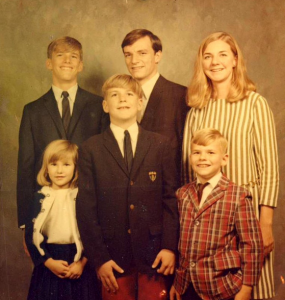

2) What does it mean to look at photographs of families that we do not recognise? There is a distinction between those that we know, and others that remain out side of our scope of recognition. I often look through junk shops, and car boot sales at boxes full of discarded family photographs. Janet and Peter – Magaluf 1984, the Jones Family – Christmas 1973. The captions further estrange us from the content of the images – they remain archetypes, their narratives undisclosed to us, fixed smiles and stiff postures. How do these images operate? When Nikolai Ishchuk takes images of people that he doesn’t recognise, he is using the photograph as a form of data. Something that can be edited and remixed at will. This unknowingness enables us to project our own narratives onto the images, they becomes more like mirrors. It is part of the natural life of every image – they end up concealing more than they reveal.

3) There are many different historical functions for representing the family. Some include, solidifying familial relationships, asserting normative models of behaviour, demanding recognition and visibility, and showing the ‘family’ in their best light. I like the idea that most family photography is about looking good to ourselves. Of course, social media has done much to shift the visibility the private sphere of the family. Historically, you can make a cursory distinction between middle class and working class forms of representation. Depictions of a monied class often go hand in hand with a form of soft propaganda. When I think about the representation of working class voices at the advent of photography, I think more about documentary forms allied to a social agenda. Roland Barthes talks extensively about photography’s ‘correspondence to the explosion of the private into the public’. For Barthes, the photograph aides the consumption of the private within the public arena. Photography becomes central to new forms of political visibility – visual representation becomes another currency. How does family photography operate under these conditions?

4) The rise of the family as a social unit coincides with the formation of the Nation State and with it an understanding of privacy and ownership. We can see a concurrent interest in diary writing in the 18th century and newly emergent class that arose through new economic forms. Where the diary contributed to the formation of interiority and ‘expressionism’. The family image, as painted by leading artists of the day, was a tool to assert forms of cultural and social authority. Thomas Gainsborough’s ‘Mr and Mrs Andrews’ (1750) is typical in this regard. It is an image that conflates two distinct genres – landscape and portraiture. The lap of Mrs Andrews remains unfinished, and it was left deliberately blank so that a child could be painted in a later date. It is an image about proprietary, the private sphere of the family portrait is used to assert class and ownership. The couple are situated just in front of the Oak tree, further establishing a sense of natural entitlement to the land pictured. The (monied) family image is a public statement of private entitlement. Celebrity images act in exactly the same way – increasingly we trade privacy for visibility. In network culture the currency of ‘the private’ has become subject to devaluation, so we must provide more and more of it to keep up.

5) If we take the word ‘family’ back to its etymological root it rarely meant ‘parents with children’, rather it was more aligned to how we would use the term ‘domestic’ today. Originally, servants and relatives, even boarders and lodgers would be described as ‘family’ of a household. We could look towards platforms such as Facebook et al, as using an earlier understanding of the family. Personal photography is now shared to a much broader network of associates, and friends – I think you can see these ideas in the work of the Photocopy Club and Claudia Sola’s work. How do we start to formulate a more fluid sense of family representation? What gets put in and taken out of representation? How do artists find new forms to arrest the normative models of 99% of image production? The artists in Family Politics, in different ways think through these questions in new and compelling ways.