A journey, for example,

begins with a voice calling your name out behind you.

This seems a convenient arrangement.

How else would you know it’s time to go?

On the other hand,

Who is it?

I take this section of Anne Carsons’ Glass Essay to demonstrate how the alignment of two women’s experience— in this case Carson’s heartbreak understood through the rupture of Emily Bronte’s relationship— may foster an external appreciation that the interiority of the self is fragmentary and susceptible to change when interpreted through another’s depiction. The Glass Essay describes not clarity but circuitousness, and Carson’s poetic work explores the nature of eros (the Greek god of sexual attraction and life force) and loss through bodies and emotional boundaries. By tracing an ephemeral experience through that of someone else, Carson’s Glass Essay raises complex questions of how and why we might choose to use linguistic and visual frameworks to retell a story which otherwise might cease to exist.

Scenes of places that have passed, or epitaphs of others are bound to principles of how memory is at times non-linear. Non-linear in the sense that its slippages present what we cannot quite fathom as whole images and memories, where feelings of others manifest as abstract formations, traces of the past cemented in the present. How can, and do we embody memory visually? Perhaps memory in the visual documentation of others can allow for an existence beyond temporality? Images can render as a carrier of memory— a form of recall. Freud termed this exploration as a ‘screen memory’, which defines how we process emotion visually whilst asleep. In screen memories, strong emotions are captured in our subconscious, as a container to archive the past, present and future as a type of portrait.

But should every portrait tell a story? Carson demonstrates how an autobiographical portrait can come into being through aligning two peoples’ ephemeral, emotive experience. But is drawing an artistic medium which can continually transform when its context is changed and reevaluated? A selection of entries in this year’s Jerwood Drawing Prize illustrate identity through the confrontation of reconfiguring another by virtue of portraiture. A traditional framework of portraiture means producing images which reveal characteristics of the subject. Portraits, by their very nature, present a specific enquiry into the depiction of an individual’s mood or character, their subjectivity and personal attributes.

How can we use portraits to ‘live or imagine otherwise’? Here is one way. The orchestration of such imagery presents an undoing of absence in Henriette: Quiet Memory 2017— Caragh Savage, which demonstrates the continuity of representing the recollection of a subject through the memory of the self, as a meditation on what we can and can’t define visually. Savage’s drawing depicts a sombre figure peering astutely at the viewer whose expression is implacable; ungrafted and impertinent. There is a ritualised distance between the artist and subject here— one which appears much like the movement of water— the face seems submerged in a background setting— a dreamlike sphere of the supernatural made accessible. It bears the composition of traditional portraiture, whilst finding itself situated in an unusual, indeterminate setting. It acts as a simple reminder that the face of others, much like our own, can indeed be a mirror, and it is in that mirroring we can come to know ourselves and the realities of others more astutely.

Levinas writes in relation to the face being the most exposed and vulnerable part of someone else is apparent through ‘the presence of the face, the infinity of the other’.[1] He means we come to know ourselves through the faces of others— their expressions and personal attributes and the way we might make sense of that which beckons our attention is rarely understood the same way twice. The changeability of the face of another’s, becomes twofold when the idiosyncrasies are laid out to the viewer, characteristics which may transcend their two dimensionality.

*

Last late spring —when dew on the leaves was potent— and crisp leaves crunching under foot, all pale orange, I found myself standing in front of a Rothko at Tate Modern. I defaced the red of the painting and it defaced me, eloquently, seductively, through the myopic vision of a large canvas, looming over my body. I found great comfort in seeing a figure rise from an ever-darkening background, a fraction of solitude which met my senses for only a few minutes. The intricacies and illusion of spotting a nondescript silhouette, prevailing before me within the square, felt like a formative moment in querying where, and how the self is translated through visual language.

When I view portraits, I like to partly consider myself to be experiencing the subject through the rupture of identity, creating slippages in who we conceive that person to be. Such artworks allow for an unfolding of characterisation; a dissonance which allows one to witness the composure of how we might locate memory in future visuality. Involuntary memory (explored famously in Marcel Proust’s In Search for Lost Time) reminds us that the inconspicuousness of unconscious can be evoked through the most incidental signifiers. Albeit, the function of such unprompted thoughts unfold before us like a myriad of ephemeral colours and feelings. This is not to say that the images here embody such a didactic terrain, but it seems only fitting that they do transcribe knowledge of another visually. A figure wrought by non linear prose, the manner by which Proust’s thoughts emerge to his reader as a transference of personal experience, a portrait which quivers between the conscious and subconscious, surrendered to the emergence of recollection and abstraction.

Portraits are, then, not just visual depictions of subjects but a likeness. On The Death of a Ringmaster’s Daughter (2017) by Lewis Chamberlain reimagines how we might archive the death of others atmospherically, as opposed to a figurative depiction. A constellation of objects, including a feather, bone, leaves and plant jupiter all contribute to a hanging cabinet of curiosities. The artist explains that the inspiration for this image derived from a photograph of a child dying in a circus fire. Hanging much like a child’s mobile above a cot, the drawing has an aura of innocence, perhaps as a declaration to youth. The suspended objects, somewhat reminiscent of a circus trapeze, denote portraiture in a more abstract terrain—in that a portrait of those who have past can take form through the materiality of objects. In considering the author, artist and subject of these images, the relationship between the two blur; and as a writer viewing these portraits I embark upon a journey into the framework of others lives, if only for a moment.

To portray who someone was, without being led astray into naming what he/she/they is, furthers the intangibility of memory in the context of visual autobiography. We rely on one another to narrate eachothers experiences and lives, whilst alive and after death. It is these essentialist binaries of which we live in and from (and who we may live on for) which is most explicit in Helen Barff’s The Dress I Wore To My Dad’s Funeral (drawn with fingers in graphite dust) (2017). The drawing – sublime and dark, like black – tar portrays a faint silhouette which almost seems pinned to a wall, falling horizontally behind a white curtain. It demonstrates autobiographical memory through the materiality of clothes. The boundary between real and imagined selves is most poignant here; the figure appears ghost like, but the title signifies to the garment worn at a funeral. The viewer is left perplexed; is this a documentation of the father, through the haunting imagery of the daughters dress?

But what is left behind, when the face of the other is reconfigured through drawing? Generating a life narrative through objects is apparent conjointly in Portrait of Father Sitting (2017) by Tahira Mandrino, which allows a shifting of sentimentality to come forth through the simplicity of a comb. The comb; nondescript, everyday, and uneventful, encapsulates the missing of a parent, as a symbolism of mortality. Autobiographical memory prevails through the guise of the object— where a self narrative and storytelling is speculated on by the viewer by virtue of possession, and not the face of who ceases to exist. The uniqueness of each life, then, does not mean a life experienced in isolation; but rather a togetherness through memory, and archiving of experience through the mark making of another.

Adriana Cavarero describes the becoming through the act of another in the following passage:

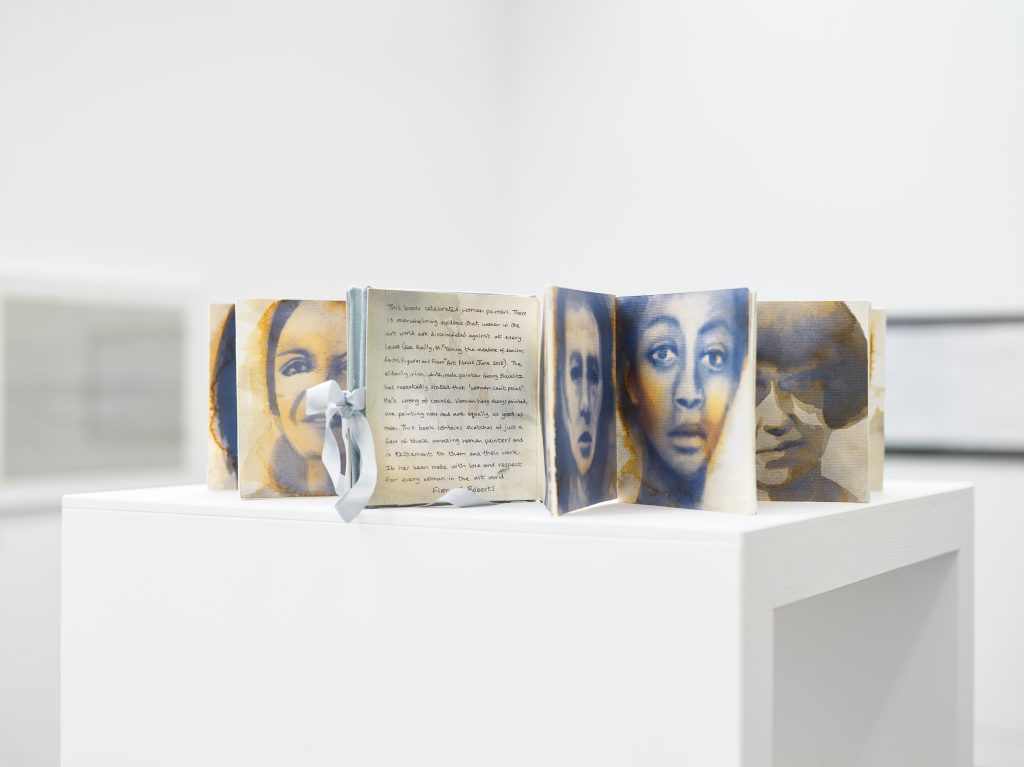

‘the self comes to desire the tale of his or her own life-story from the mouth (or pen) of another’.[2] What she is referring to is the space whereby we rely on the action of one another in order to have a narrative of ourselves, whether through portraiture, written word or oral histories. But what happens when these identities are intertwined, placed alongside one another and grouped? FAO Georg Baselitz by Fiona G. Roberts brings together the portraits of women including Georgia O’Keeffe, Alice Neel, Marlene Dumas and Tracey Emin in a booklet, each image composed in ink. It confronts the perceptual discrimination that female artists are often unrepresented by arts institutions, as an optimistic proposition of how such female artists need more visibility, for their artistic endeavours and position under patriarchy. Rendering much like a visual biography, it allows the singular portrait to become a gesture towards a multiple, collective entity.

This booklet seeks to collapse proximity to, or approximation with the self. It asks us to consider who we may be aligned with in this instance of a book, or moreover how we unite through the instance of materialities as women. As Terdiman states, every moment we attempt to reproduce is a ‘present past’ and is reflected here; women have always retold stories and narrated the lives of those they love and admire. In placing these women next to each other, the artist has manufactured a statement of how we chose to remember individuals as collectives, and the narrational threads which tie them together. Were these portraits ever intended to exist alongside one another, as such intimate pursuit? Perhaps. I like to think of this book as an attempt of de-individualized living, representing and grouping, where juxtaposition becomes an alternative to metaphor making, through the faces of others. As Janet Malcolm denotes in The Silent Woman, ‘we all move through the world surrounded by an atmosphere that is unique to us and by which we may be recognized as clearly by our faces’.[3] And thus it is this movement, this dexterity of the self, which has the capacity to unfold and change through the visual depiction of portraiture.

[1] Emmanuel Levinas, Totality And Infinity (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Duquesne University Press, 1969) p. 213.

[2] Adriana Cavarero, Relating Narratives (Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2014) p. ix.

[3] Janet, Malcolm, The Silent Woman. Third Edition (London Granta 2012) p. 28