I seem to spend much of my time these days thinking about three or four things.

- The fact that other places exist. Now. Somewhere else.

- Actions occurring simultaneously. Now. Somewhere else. And normally unpleasant.

- Whether I have spent my day in a worthwhile manner.

- Following closely on from 3., how I might define and therefore improve my accomplishment of whatever it is I am or might be doing that is of worth.

Last night on earth…

First morning…

It might justifiably be observed that such thoughts, or rather, the opportunity to pursue them, to dwell even briefly within them, are the privilege of those in the 1% globally. Certainly, if not related to income, I live as one of that tiny minority, as we all do who find ourselves in the UK, regardless of class, property and wealth; not least because we can still depend on the fact that a more or less supporting external reality is, and that it endures. A structure is in place. Yes, it is threatened. Yes, it requires constant defence and advocacy. Yes, nothing can be taken for granted. But we are vast distances from those for whom a waking continuity is absolutely nothing to be relied upon (last night I watched Claire Denis’ genuinely unsettling White Material, with its portrayed forms of organisation – oppressive and benign – as vulnerable as crops to drought).

I should say that I do not recline, chaise-longued, and ponder existence through the weekday afternoons. More, these concerns exist like a static, an untuned radio interference, behind the stations of my overtly declared pursuits at any given moment (it has been said that the white noise between clear tuning is the sound of the universe, in which case such thoughts seem less indulgent, and more inevitable, than at first expression).

I am sure I am not alone in such reflections. All of us who attempt to navigate some more or less conscious path through the traffic of things – that is, the world – find these or similar worries rising more and more frequently these days. Globalisation, the post-industrial, the ecological, forms of systemic unravelling, technological acceleration and the attendant volume of information (without its equivalent insight or knowledge)… these and many other factors inform and impose upon our crowded heads.

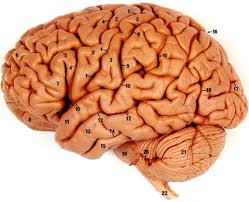

Strange to think that if I whisper into your ear – as you sleep – I am speaking directly to your dreaming brain, only centimetres away. Your mind, however, who knows where that might be, running through the trees that edge the backcountry roads, free canine; appreciating flight; climbing the peaks of long dead stellar formations…

In Patricio Guzman’s astonishing film essay Nostalgia for the Light, a likeable young astronomer confirms to the film-maker that the present does not exist. That the inevitable delay in our sensory receptors means that every act, encounter, impression reaches us after it has occurred, however intimate or intense. The present is constantly retreating, tidal, away from us as we follow it. We live finally in the past, at least in terms of experiential physiological consciousness. If this is true – and it’s hard finally to challenge – then the much vaunted goal of living ‘in the moment’, in the ‘present’ of a heightened awareness to all things, from washing up to making love, takes on a more complex hue. We reside in a constantly unfolding memory, making it step by step as we recede into the future, a door at the end of a filmicly extending corridor we can never reach. Where then, in this trajectory of displaced immediacy and aspirant attention, should we place ourselves?

Emma Hart’s work for TNK makes central one of the devices that, for a few decades at least, has served more often than not as a measure, both personal and public, of our place in the living and recollection of our own times. The television – especially in its phase as signal hearth to our collective growing – provided both a register of actual and existential time, and of the life undertaken in those times. That its images were, until relatively recently, irretrievable once broadcast, only served to accentuate its potential as an external echo of our own interior relationship to memory and the often expressive urgency of what has been seen or touched us.

Hart has written that her desire in relation to image-making is less concerned with what those images might be ‘of’ than what they are ‘doing’. What’s interesting about television is that it does both. Its of-ness often is – embodies – its action. The fact of it, that it continues, around and beyond us, as a generally reassuring frame of onward making, underscores its importance to private and national identity-building (there’s still a reason to take over the television station, although it’s increasingly harder to know where it might be, or which one is most significant).

Rain on Victorian brick; a sky of smoke and milk; slow Monday, even the road is hesitant.

In her TNK piece, Monument to the Unsaved, Hart offers us a set in the old way, pre-switchover, a machine that is functioning kin to the other domestic appliances – irons, vacuum cleaners, with which it shares room space. Her television is not an autonomous system, independent of all stimuli, servicing its viewers Hal-like, with a clinical detachment. Rather, it’s both a measure of, and responsive to, audience impulse and hope. Hart’s proposal here – that the stutters, stammers and judder of consciousness, thought, memory and motivation can find a correlative in the layered glitches of early image-recording technologies – taps a poignancy that is hard to separate from the means of that mood’s manufacture.

We are all affected by the often corporate prompts towards a shared form, an index of recollection: the grimly smiling holiday photos, the cheese, the panning shot from the hotel to the sea view. So it is with our own appearance within those calculated planes. This becomes even more charged when the image originator is larger than the familial, when it is part of, and promises immersion within, the ongoing story of the socially seen.

Hart’s appearance on the long-running (long enough to grow up alongside) Channel 4 quiz show Blockbusters in 1989 perfectly illustrates this. Who can fail to feel the loss of that evidence when her father records over it with the film Moonraker (a particularly weak title in the Bond franchise). And yet, in this simplest of everyday acts, larger forces and dynamics can be glimpsed. This erasure of the smallest personal might stand in for the loss of the individual narrative in a year of seismic international shift. The human gesture that is a quiz show appearance, reliant on chance and luck and skill, is lost to a techno-corporate image franchise celebrating its own form – in both production and theme – of globalised, quasi-imperial oppression (a sidebar irony too in its counter-reminding that the BBC recorded over much of their own coverage of the lunar landing 20 years earlier)

How we live alongside others, alongside events – large and small, horrific and weighed in grace – and how we find value in our own acts and being, towards ourselves and the world; these surely are the questions of our time. Erase and delete, erase and forget, erase and… forms of closure, implosion, threat, dissolution, the slow or sudden apocalypse of the known and assumed… like all societies living on a threshold, on the very frontier between stories of itself, we can immerse unthinking in created fantasias of destruction (the psychic advance guard of what might come) or we can learn from such ‘safe’ encounter what must be salvaged in the actually existing, slipping present.

Crisis survived is by definition a prompt to wonder at the everyday miracles that also made it through, at what is and is again: clean water, the gleam in wine, the working of a light switch, the jingle-jangle of a playground ripe with children. These are the monumental things, whether saved or woven into ongoing forgetting by replacing themselves each time we rise. Would we rather lift hewn stone to our remembering, or follow the passage of the wind through the singing branches, the breath of what would be invisible without the tree. A deep green collaboration. Here is the dance between matter and meaning, between signal and transmitter, the fluid architectures of existence.

What cannot be saved: our lives. What can be saved: how we live our lives. In every human moment, there is a hand somewhere in the picture, seen or felt, its kind press. An offered hand – I am, you are, and we. The great and lasting monument, one nobody builds, except in warm attention, except in passing air, inside the memory of the world – a mercy and a process. A kind of bread. A hand. A hand upon the buzzer, a hand to press ‘record’.