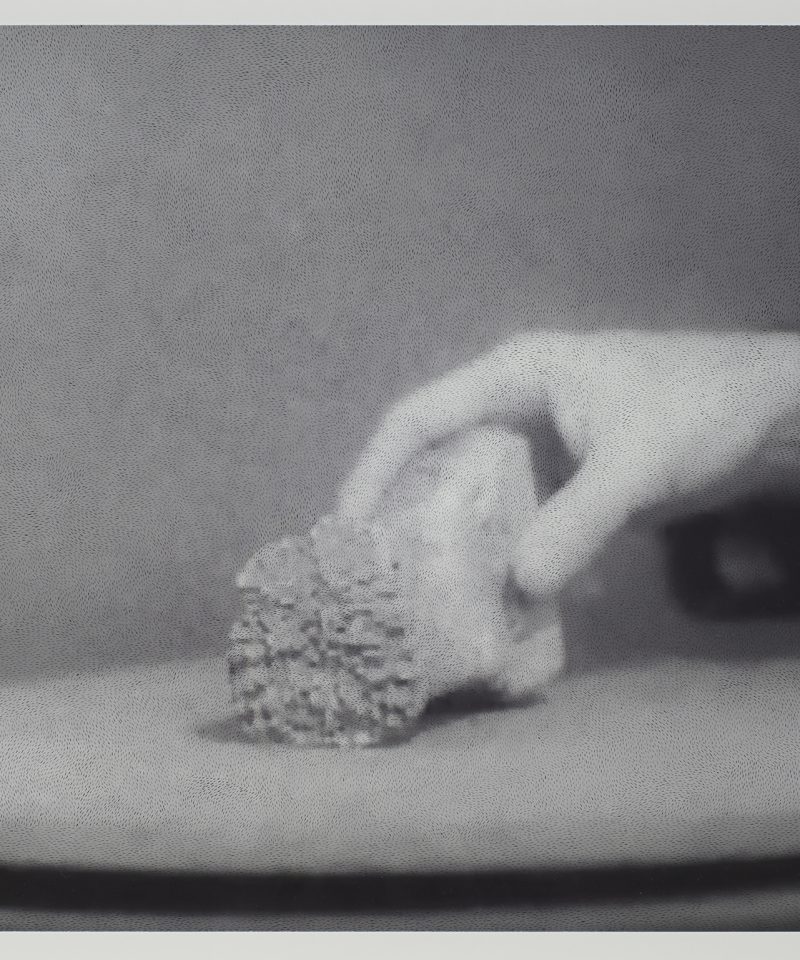

Maybe it’s an obvious thing to say, but when I think about drawing, I think about hands – hands as ‘authentic’ appendages, contraptions of tactility and communication, brutality and sensuality, through which we shape the world. Drawing suggests a progenitive link between maker and art object; a link embraced by some proponents of a conservative, craft-conscious art that stands in opposition to the realities of the contemporary art market, with its armies of underpaid interns and fetish for high-spec industrial sheens. But we could see it another way. In the mid-60s Allan Kaprow articulated the idea that painting might be considered as a record of a performance, rather than the eschatological terminus towards which all art-making must tend. In shifting emphasis from materiality to temporality – by figuring the work of art as a vessel of invested time, the lasting relic of ephemeral gestures – he suggested a different model of engagement with pictorial representation, in which all marks are unavoidably the record of their maker.

We like to watch Picasso draw because Picasso was ‘a genius’. Witnessing his body at work, his guiding hand, confirms the authorship of the mark, his mark, on the page. This romantic view of artistic production is reminiscent of divine paternity: the hand that reaches out to Adam, shaping him from dirt; the male maker’s hand as an echo of God’s. Picasso’s fluid and instinctual use of the charcoal (he doesn’t appear to be deciding which marks to make; they simply happen) also illustrates Heidegger’s notion of the ‘ready-to-hand’, which, to oversimplify, describes our practical relation to things that are ‘handy’ or useful.

And then there’s Matthew Barney, who twists the idea of drawing as an expression of bodily skill into a bizarre and self-regarding display in which the drawing (as in the noun, the art object) is the tortured product of an athletic overcoming of obstacles he built himself. Barney’s Drawing Restraint works are fundamentally silly, but their will to mastery illustrates an important etymological point. ‘Hand’, from the Old English ‘hond’: power, control, possession.

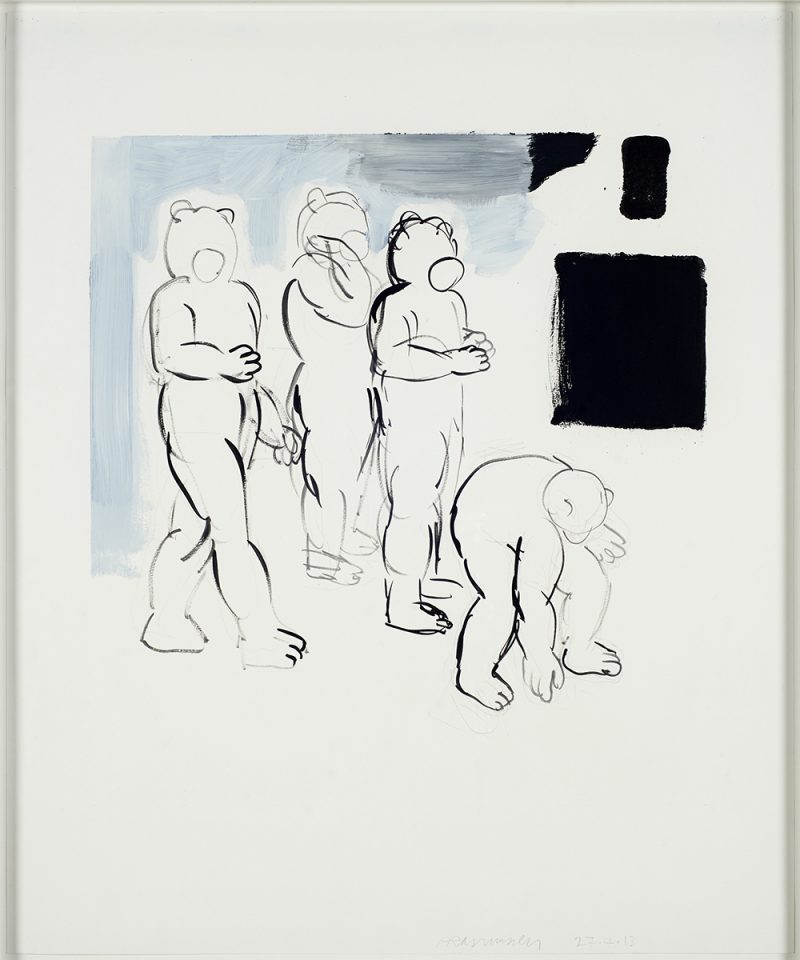

It would follow, then, that the loss of the hands means the loss of control. There’s a scene in the film version of Akira (1988) when we enter the mind of Tetsuo, the traumatised orphan struggling to deal with the onset of psychic powers. The world around him begins to crack and shatter, fissures shooting through the concrete like Lichtenberg Figures, but this is no ordinary earthquake. When the cracks invade Tetuso’s body (and by extension, his mind), the first things to go are his fingers, his hands, his wrists. Dissolving hands prefigure the dissolving self.

Dissolution isn’t always bad. Ben Lerner’s new novel 10:04 contains a passage in which the author compares two depictions of disappearing hands, and extrapolates from them a mediation on possible futures. He analyses Joan of Arc (1879), by the French naturalist painter Jules Bastien-Lepage, in which the future saint is shown haunted by angels, gazing towards her destiny as a martyr. (Lerner also wrote about the painting for frieze.) Bastien-Lepage was criticised at the time for his failure to reconcile the spiritual and concrete dimensions within the painting – the floating figures of transparent saints and the rural realism of the world in which they appear – but for Lerner this creates a ‘glitch in the pictorial matrix’: Joan’s searching fingers become transparent at the tips, intimating her future transformation, through death, into a saint. Lerner contrasts this with the scene in Back to the Future (1985) in which Marty disrupts the prehistory of his family, making his siblings fade from a family snapshot. Lerner deploys these images as symbols for the presence and absence of certain futures, and the hands motif neatly echoes the language of clocks: hands are how we measure time.

And there are hands that persist after the death, the collapse of an individual’s futures: uncannily active body parts, like Thing from the Addam’s Family, say, or the twitching, seemingly reanimated CGI hand that features in Heads May Roll (2014) by Benedict Drew, recently on show in Matt’s Gallery. HD technology allows us to extend the human image into screen-space, creating ambiguous forms of imagined embodiment that thrive in the ‘uncanny valley‘. Drew’s work harnesses fragmentation – bodily, but also formal – to make a point about the strange abjection/empowerment (virtual) images produce in relation to (actual) bodies.

If hands suggest tactility between bodies and objects; they also symbolise wider forms of apprehension and communication. Drew’s hand is evocative of ancient, ghoulish tropes of Horror fiction, Frankenstein in particular (note the eerie green background of the image above, reminiscent of Hammer Horror lighting effects); they also suggest forms of embodiment beyond the cyberpunk dream of the human corpus infiltrated and enhanced by gadgets, nanotechnology, wires and nodes. At the end of Terminator II, the cyborg’s complete moral conversion, from murderous machine to surrogate father, is communicated his final, dying gesture as he is consumed by molten metal. The universal hand-signal of approval, affirmation, positivity and friendship constitutes the ludicrously poignant crux of the film, its non-verbal emotional payoff.

If hands can communicate the inner emotional truths we (or Arnold Schwarzenegger) can’t quite put into words, in the context of crime and punishment they more straightforwardly confirm our identity, and, by extension, guilt. Towards the end of Seven (1995), Kevin Spacey’s character John Doe walks into the police station of the unnamed city in a Christ-like pose of surrender, in broad daylight, wearing a white shirt splattered with blood. His arms are ribboned with red streaks; his fingertips are swaddled in surgical tape. Detectives Mills and Somerset have been hunting Doe for months, but have thus far been bamboozled by their failure to identify him by his fingerprints (Doe leaves plenty at the scene, but they aren’t on any databases). This is because he doesn’t have any: John Doe slices the skin off his fingers between every murder, and the skin grows back in different patterns each time. This small if brutal act of self-mutilation effectively renders him invisible in the eyes of the law.

These preliminary thoughts – most of which aren’t actually related to drawing at all – will frame later investigations into the works in this year’s Drawing Prize. In a few days I’ll be posting an interview with Kate Morell, whose drawing A.V.M. 1954 screenshot 2013-12-10 (3) confronts the politics of touching and display in relation to archaeological objects.

In the meantime, here’s the customary cringe-inducing, mildly funny, tangentially related YouTube clip. (This is the internet, after all.)