In fact, a real meteorite was supposed to also attend the exhibition. Buenos Aires-based artists Guillermo Faivovich and Nicolás Goldberg had planned to move a 37-ton-meteorite named El Chaco from Argentina to Kassel, for an installation titled A Guide to Campo del Cielo. The controversy started when Moqoit First Nation peoples started a campaign for aboriginal rights – claiming that the displacement of the rock was a form of colonial appropriation.

Documenta was a fantastic experience. As you’d hope, it was full of some of the best art around today. And the art generally seemed more important than the theory.

Which was refreshing, because art usually messes up ethics – as was the case with the El Chaco meteorite incident. For example, curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev focussed on was ‘the knowledge of animate and inanimate makers of the world’, as well as a recurrent motif of what she calls dis-placedness. Which leads her to ask of the meteorite ‘does it have any rights…?’ If she was serious about human rights issues – and even the ethics of animal rights – the question would not even be asked.

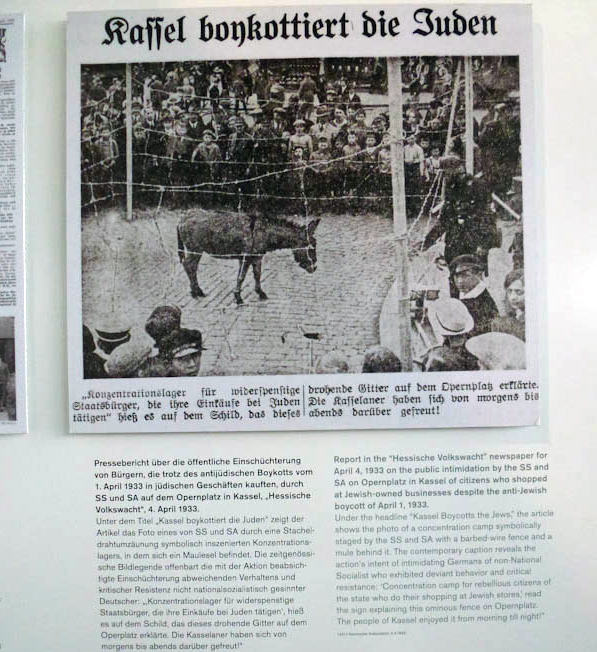

One work that I couldn’t stop looking at captured a dilemma of rights – the human and animal (rather than ‘animate and inanimate’). The Disobedient (The Revolutionaries), 2012, by Sanja Iveković, was a display of stuffed toy donkeys in a cabinet and a photograph from 1933. In the latter we see a donkey in a barbed wire enclosure, and a Nazi officer standing guard. Bizarre and disturbing, the image was taken on the streets of Kassel 80 years ago, and records a public demonstration of what would befall ‘stubborn citizens’ if they refused to work. A couple of days later I was on the other side of German in Berlin, and stumbled across the image again – this time in the impressive new Topogrophy of Terror Museum. Dis-placedness indeed. Here’s the image from the latter museum: