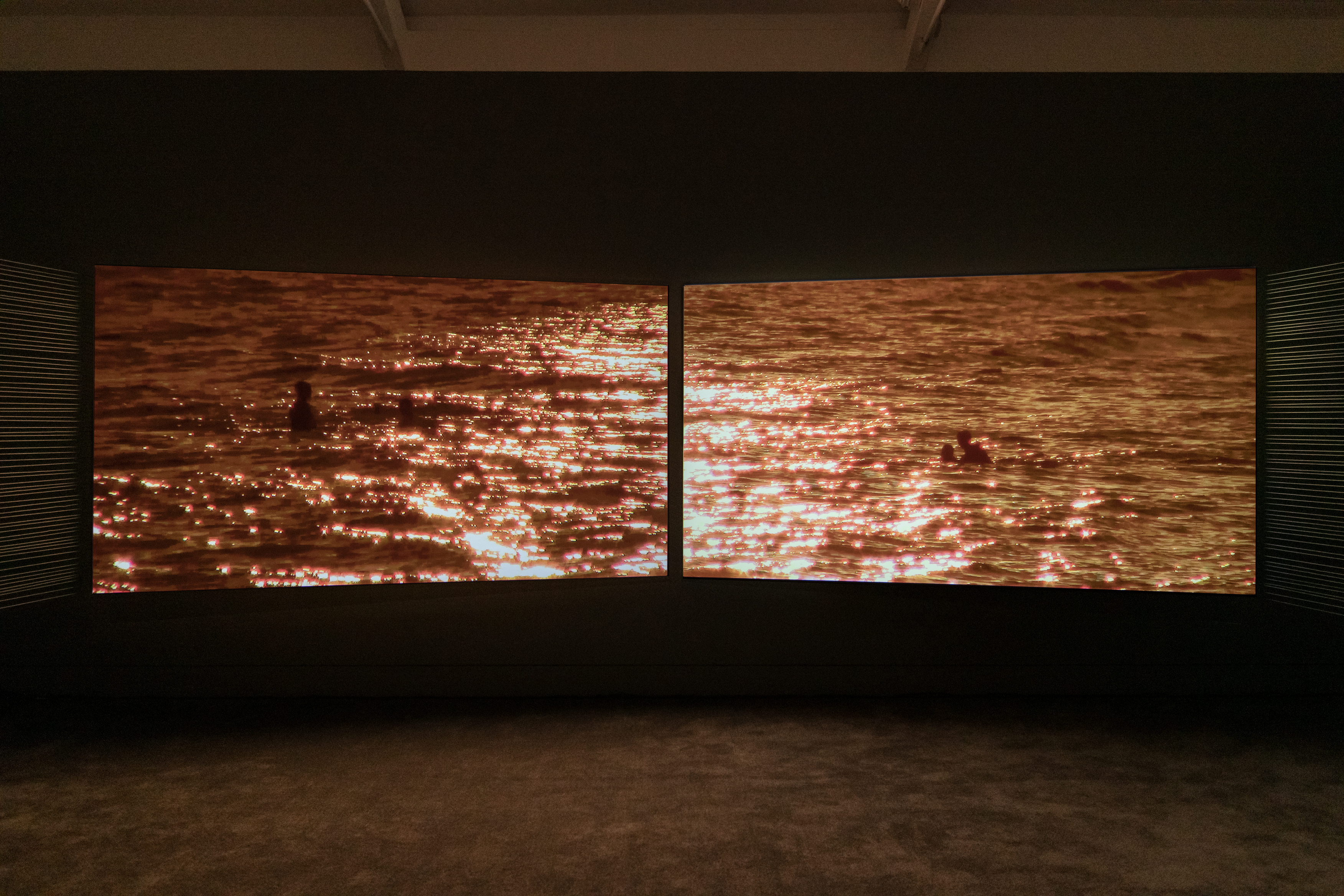

For The First Baby Born in Space, a new film work by Webb-Ellis, starts in the middle and works outwards in opposing directions, looking both backwards and forwards. Following a group of wayward teenagers living in Whitby, on the outskirts of the UK, it made me nostalgic for that charged time of becoming. Reclining on the rolling bamboo and cushioned seats inside the installation at Jerwood Space, we are drawn into the world of half-formed beings we all once inhabited. Where ‘hanging around’ town was the cherished activity and the ecosystem of your social ‘gang’ was all that you cared about. The film focuses on summer holidays full of the usual teenage antics; swimming, fishing, sailing, fires by the beach, careening dangerously down roads on mopeds and bicycles, braiding each other’s hair and the synapse-stoking fantasia of the local fairground. Simultaneously, it reaches forward to a future of uncertain possibilities. What will become of this rogue young group? What do they want from the world, and what happens when someone starts asking them questions about the world we live in? Questions they’ve never been asked before.

‘We’re just floating around aren’t we?’

For Jerwood/ FVU Awards 2019: Going Gone, artists Webb-Ellis have gotten an inside look into the youth culture of the British seaside town, Whitby. When they first approached the group at the end of the pier crab-fishing, what began was a trust-gaining process that led to an unconventional friendship. Two artists and a group of boisterous teenagers, ranging in age from thirteen up to eighteen, spent the sticky summer of 2018 together, roaming around town. Avoiding saccharine allusions of youth, For The First Baby Born in Space presents a seductive thread of fragments that feels like an authentic insight into their time spent together and considers the position of the human. Unfazed by the camera, we are given snippets of their stories, desires and fears. The ‘always waiting’ part of youth – for the next party, person or obsession – is made apparent, just beyond the horizon. As two girls huddle together beside the fire, we’re reminded of the intensity of friendship during that time and the bonds that felt like they’d last forever.

‘I’d love to live somewhere where you weren’t known.’

The film is punctuated with animals. Dogs swim and lie in wait, a cat prowls, a duck sits watching, birds dive to fish, one girl stares transfixed into a fish tank while another rides a horse. Similarly, these animals have no control over the conditions that will shape their fate. As the young people spend time on the pier gutting fish, some of them repulsed, others engrossed, I thought of the significance of fish in these waters. Unlike immigration, the principal motivation for some Brexit voters, the EU’s control over the seas was the prime deciding factor for many who lived in coastal towns further south in the town of Grimsby. Until the 1970s, when Iceland closed its fishing grounds to the British, and the European politicians mutualised Europe’s seas, including those Britain laid claim to, fish was the dominant industry. A lingering bitterness for the loss of the vibrant catching industry that once was is what remains. Unbeknownst to these teenagers, they look out across the North Sea, a contentious site as the fishing domain now shared with the Spanish, French, Danes and the Dutch.[1]

‘Once I had a thought that maybe our life right now was all a dream.’

As the scenes move from the calm, sun-setting seaside to the dizzyingly fast, spinning rides of the fairground, the film gathers momentum. Glitter, eyelashes and nails all applied, the anticipation of the evening is unleashed. The teenagers run amok amidst mechanical bulls, roller coasters, spinning tops and the whirling fit-inducing frenzy of the Waltzers; the nucleus of the fair. As dusk settles, the Waltzers are used as an alternative club-space for under-eighteens, I am told by Webb-Ellis. With the DJ at the helm broadcasting pseudo-transgressive techno music, lasers and dry-ice, the teenagers are given access to a rave environment they wouldn’t usually be allowed to attend. They can roam around dancing while the ride operators, who ride the ride, circulate, spinning the booths while remaining apparently unperturbed by its rough motion. Webb-Ellis seductively draw the viewer into this world of teenage delinquency.

‘You could have all these friends on facebook and still feel lonely. I hate loneliness.’

Gradually, the trance-like movement of uninhibited dancers takes over as the split-screen film seems to climax in a choreographed sequence, filmed during a workshop with dance artist Lucy Suggate. Set beside the rave scene, the footage of the dancers weave together with the waltzers to create a sense of surrender – to the conflicting time within growing bodies, to their lack of control of the conditions in which they come of age and to their personal desires and fears. The accompanying song Everything all the Time by Wildbirds and Peacedrums provides a particularly mesmeric soundscape to their undulating rhythms as the dancers embody and respond to the shifting moods in the music.

‘I believe in reincarnation.’

In The Future Body at Work, Kasia Wolinska & Frida Sandström notes, ‘the body’s capacity to resist, endure, and transform gives rise to dance in its autonomous form, relying on both historical actions and future endeavors.’[2] Dance, in this sense, acts as a tool of cognitive apparatus for the young people to connect with each other in thinking through ways of being in the paralysing present. Specifically within the ongoing stasis of Brexit, we see the group thriving in a collective effort to devise new identities in movement, without predetermined notions of ability or expertise. There is a sensuous flow in their movements that synthesise into one body of people then ricochets into an expression of each individual’s rapturous gesture. Watching these focused moments of intensity is in stark contrast to the aimless wanderings throughout the rest of the film, and is captivating to behold.

‘I feel like no adult wants to hear me.’

Throughout the film, there is an underlying current of apprehension for the future that remains constant. Particularly in the hypnotic frame of a girl riding a horse, there is the contradictory feeling that she’s not making progress. Yet with sunsets, fireworks and stars there’s a lot of time spent looking up. Despite the political context, which is inclusive of devastating climate change, For The First Baby Born in Space retains a subtle optimism, and provides an imaginative and evocative inquiry into a group of young people who are all too often overlooked and dismissed, deemed unworthy of being listened to by older generations. Webb-Ellis have not only given them a voice, but have fostered a unique connection that reveals how important it is to ask the larger-than-life questions about what it feels like to be, think and move in the world when everything is in flux.

As the credits went up and we look out to the horizon, I thought of the dancer Isadora Duncan who shouted bare chested at the end of a performance, “You were wild once here. Don’t let them tame you.”[3]

[1] Meek, J. (2019) Dreams of Leaving and Remaining London: Verson (The Myth is had Britain declared its own two-hundred-mile fishing zone like Iceland and stayed out of Europe, the fishing industry would still be thriving. However, the Cod War was Iceland’s attempt to control unrestricted trawling, including by its own boats ‘that was taking more fish out of the sea than the sea had to give’ P.32)

[2] Wolinska, K. & Sandstrom, F. (2019) The Future Body at Work e-flux journal #99. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/99/263557/the-future-body-at-work/ [Accessed 21 May 2019]

[3] From a speech she delivered after a dance performance she gave in Boston in 1922. Duncan was not well received by audiences in America due to her communist sympathies. These words were shouted by a bare-chested Duncan to the audience leaving the theatre. The infamous show resulted in Duncan being banned from performing in Boston under the city’s decency law.