Jerwood Encounters: Common Property is an exhibition about contemporary artists and copyright curated by Hannah Pierce. While it’s installed in the Jerwood Space on Union Street, London (15 January – 21 February 2016), I’m going to use this blog to publish a series of three interconnected essays about One Direction, magic eye pictures, Marcel Duchamp, John Berger, Kirill Medvedev, Alexander Pope, and how copyright law and creativity have been intertwined for at least the last 300 years. This is the third.

‘Wanting a different copyright’, Cory Doctorow argues in Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (2014), ‘isn’t the same as not wanting copyright at all.’ Some parts he likes, others he doesn’t:

I like the part of copyright that says my publisher can’t print this book without getting my permission, because I won’t give my permission unless they pay me. I don’t like the part of copyright that says that I, the author, can’t authorize you to break digital locks that are put on my works by an intermediary.

An example would be the Kindle I just typed that up from. This sort of device is a ‘roach motel’ in Doctorow’s terminology, a dead end onto which material can be moved, but never moved off.

Doctorow’s prose style makes his attitudes sound inevitable, but they’re not. One of the major contemporary examples of this is the Russian poet, translator and activist Kirill Medvedev. In 2004, Medvedev renounced any claim to copyright on his work. Explaining himself in 2015, he reflected that

I was increasingly aware of the fact that in order to make a political statement an artist must not just work with “political” themes in his poetry, that is, on the level of content, but he must develop a structural, institutional alternative to the current order.

Medvedev made this gesture at a time when it looked as though copyright legislation in Russia was about to be ‘rationalized’ by Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organization (this didn’t actually happen until 2012, after 19 years of negotiations.) It was an appeal to a different sort of internationalism, a ‘gesture of yearning for the international progressive intellectual, artistic and political movement that seeks a way out of neoliberal capitalism.’

The action came to a head when the Russian publishing house NLO took Medvedev up on his declarations, and published a book called Texts Published Without the Permission of the Author (2005). Though some of Medvedev’s statements on his ‘Actions’ read as though they could have been written at any point in the last 150 years, his response to the NLO publication belonged more specifically to the twenty-first century:

I think the idea of separating the author from his text makes a certain amount of sense in the context of the internet-author, who really doesn’t have a name or a body – that is, in a situation when only the author knows of his connection to the text.

I know about this because I read it in Fitzcarraldo Editions’ English-language collection of his work It’s No Good (2015): a book which has ‘Copyright denied by Kirill Medvedev 2015’ where it would ordinarily state ‘© Kirill Medvedev 2015’.

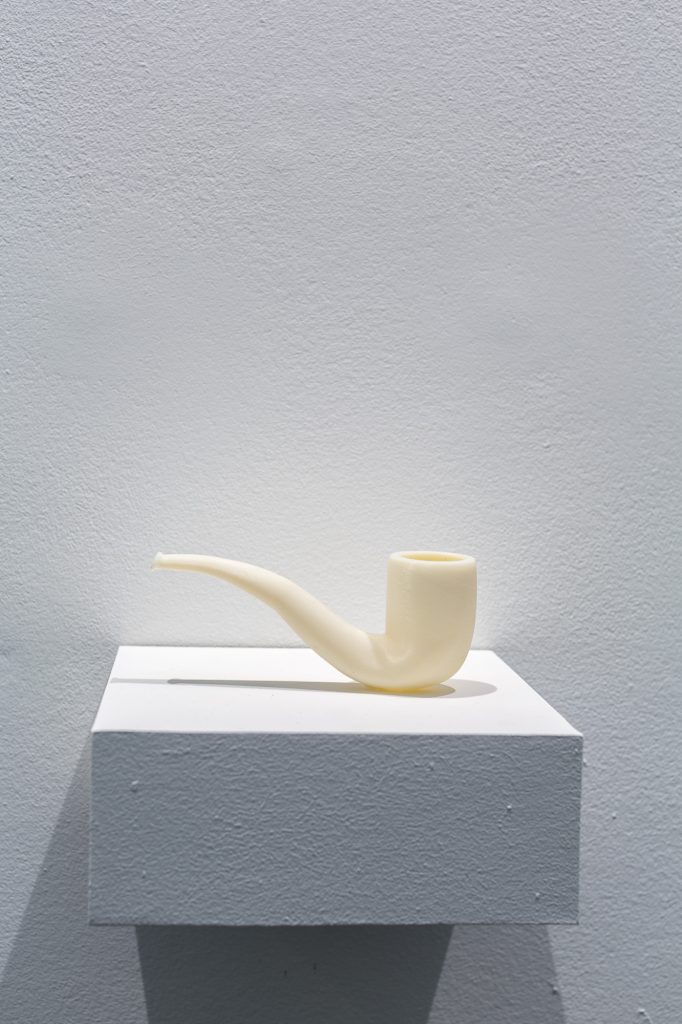

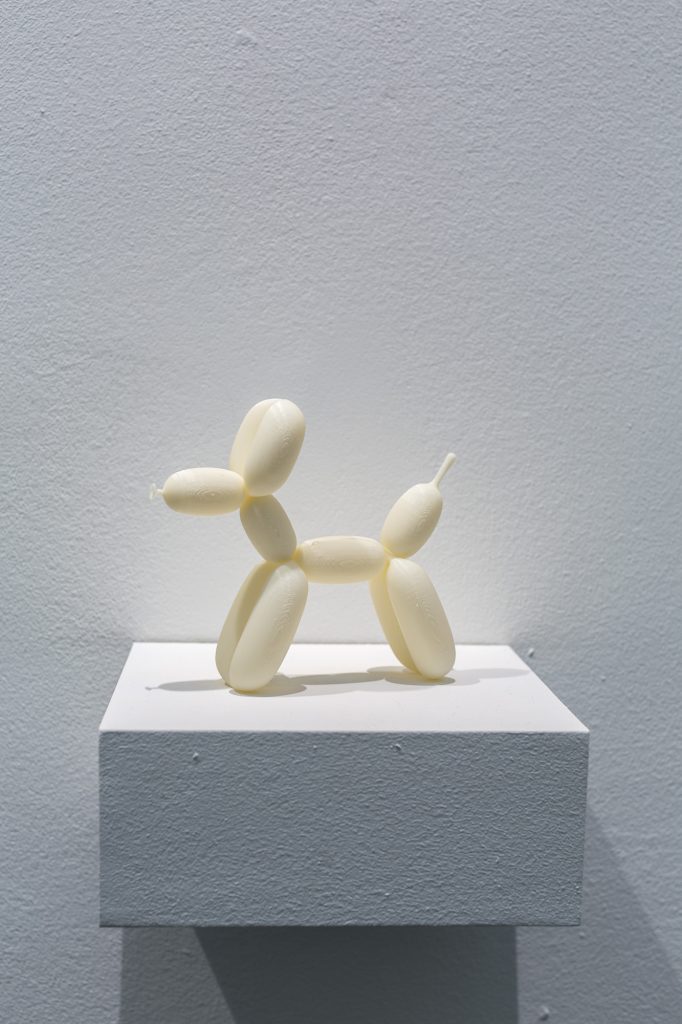

Probably the closest analogues in Common Property are Rob Myers’ Sharable Readymades. In the gallery, they appear as bone-white models: a urinal, a pipe, and a balloon dog, respective transformations of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917),René Magritte’s La trahison des images [Ceci n’est pas une pipe]) (1928–9), and Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog (1994). Myers had designers turn the works into open source files which can be printed and used anywhere so long as they remain freely licensed and are accompanied by the correct attribution.[1] Interestingly, the idea itself shares some aspects with the small terracotta mock-ups of canonical art-historical works Luke McCreadie made for the Jerwood Project Space last year.

In Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free, Doctorow advises his readers to change their attitudes to copying: rather than investing time and resources in a small numbers of copies ‘like a mammal’, think ‘like a dandelion’ and scatter a more than you can keep track of, in the hope that one or two will take root. The idea behind this is commensurate with his idea that fame won’t get you paid, but you can’t get paid without it: the broader publicity it gathers for you as a creative entity will in the long run earn you more money than the short, editioned run of artworks would. Is this what Medvedev is doing? I’m not entirely sure that I would have read It’s No Good if he hadn’t staged his action. But at the end of the Guardian article which accompanied the launch of the Fitzcarraldo edition, he wrote

Of course the question of publishing poetry and manifestos is unconnected with earning a living – you wouldn’t be able to earn a living that way in any case. If anyone’s curious, however, for several years I was a stay-at-home father; more recently I have worked as a delivery man for several companies as well as a freelance book editor.

Despite, or maybe because of this action, Medvedev can get extremely exercised about cultural ownership, more broadly understood. In 2007 he protested at a theatre which was staging a production of a Bertolt Brecht play. The theatre’s director, Alexander Kalyagin, had signed a letter in support of the imprisonment of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Khodorkovsky had been the richest man in Russia; an oil company executive who stood up to its increasingly totalitarian President, Vladimir Putin. In 2012, Masha Gessen wrote that

Because of Brecht’s anti-totalitarianism, Medvedev felt Kalyagin’s production violated not something so bourgeois as copyright, but something more important. His manifesto on copyright, after all, was ‘an ethical, not a legal document.’ It comes closer to a subtly different, non-economic area of intellectual property legislation called moral rights. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works states that

Independent of the author’s economic rights, and even after the transfer of the said rights, the author shall have the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to the said work, which would be prejudicial to the author’s honour or reputation.

Is a production by a Putin-supporting director ‘prejudicial’ to Brecht’s ‘honour or reputation’? It’s the kind of subjective decision which the judge in Luc Tuymans’ case was called upon to make, finally deciding that his attempt at parody wasn’t funny. Perhaps, then, it’s better you go and see the Common Property while it’s still up, and decide for yourself. I’m not sure if these blogs count as journalism, but according to Medvedev,

in art the reader or viewer subjects any ideology to a kind of resistance test for believability, whereas with journalism you can poison a great number of people with you yourself see that they are false, dangerous and disgusting.

[1] I copied some of that text directly from Hannah Pierce’s catalogue to Common Property.