Jerwood Encounters: Common Property is an exhibition about contemporary artists and copyright curated by Hannah Pierce. While it’s installed in the Jerwood Space on Union Street, London (15 January – 21 February 2016), I’m going to use this blog to publish a series of three interconnected essays about One Direction, magic eye pictures, Marcel Duchamp, John Berger, Kirill Medvedev, Alexander Pope, and how copyright law and creativity have been intertwined for at least the last 300 years. This is the second.

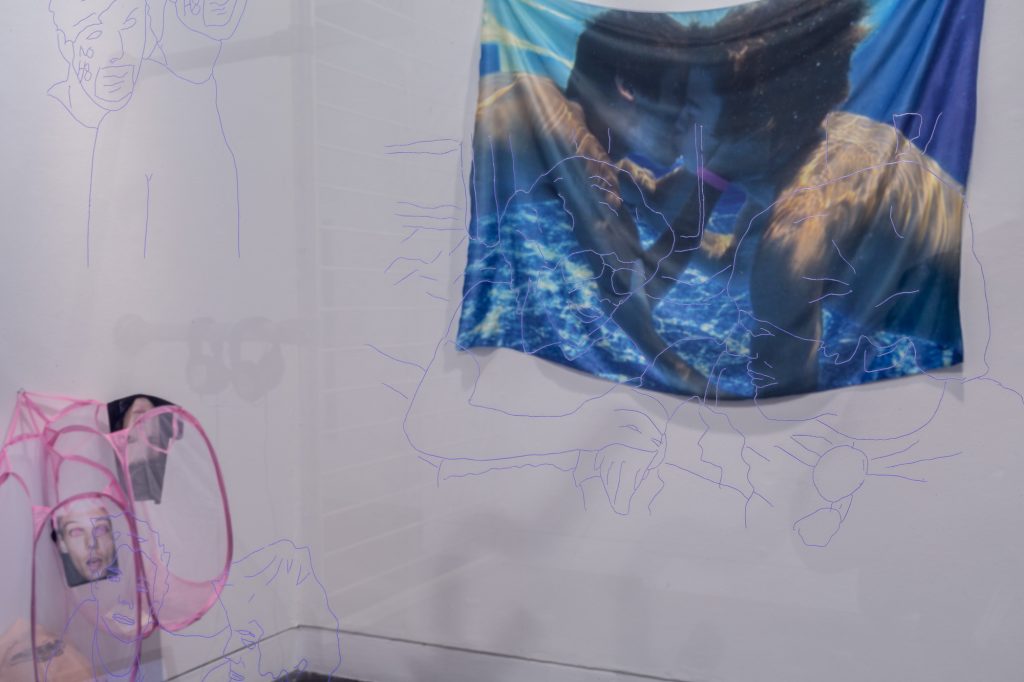

Because Alexander Pope was a poet, we’d think of poetry as his intellectual property; because One Direction are a band, we’d think of theirs as being their music. But as I explored in my last blog, it was Pope’s letters which helped shape copyright law in the Eighteenth Century, and there’s a long history of audiences being as interested in biography as in the work itself. One Direction are a product of the X Factor; they were “manufactured” live on TV, and further promoted through social media. They themselves, in addition to the social relationships between them and with their fans, are as much the saleable product as their music. This is what forms the substance of Fan Riot, Owen G. Parry’s work in Common Property.

The term here is ‘ship’, an abbreviation of ‘relationship’ which entered the Oxford English Dictionary in June 2015 as a transitive verb:

To discuss, portray, or advocate a romantic pairing of (two characters who appear in a work of (serial) fiction), esp. when such a pairing is not depicted in the original work.

The example the OED uses is from 2005, for fiction which imagined a relationship between Ron and Hermione in the Harry Potter books. A large subsection of One Direction’s audience (the term is ‘fandom’) is dedicated to imagining a relationship between the band members Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson, much of which is expressed through Tumblr-based fan art. Anna Leszkiewicz’s piece in the New Statesman pointed out that despite the skill involved in developing the ship by producing, say, an extremely lifelike computer animation of a pregnant boyband member, this is work that exists outside art galleries; despite the fact that it probably has an audience larger than much that does get shown in art galleries. These, Leszkiewicz points out

are often young women who are intellectually and creatively dismissed. But fanfiction often provides a space for young artists who might be marginalised in the mainstream to create artwork that reflects their experiences, whether it be by racebending or reimagining characters in different power structures and dynamics.

Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie were portmanteaued into the press as “Brangelina”, Styles and Tomlinson were shipped into “Larry Stylinson”. As the New Statesman and Telegraph reported, Parry staged an event as part of Common Property which featured the ‘ship’ being performed by two members of a 1D tribute band.

In that context, tribute bands seem a very twentieth-century phenomenon. They largely helped the original band and their record company; keeping the name alive and encouraging record sales so long as it didn’t get in the way of the original’s ticket sales. In theory, we might extend the same logic to shipping and “fandoms”. A key part of the story is that the band’s management are forcing Styles and Tomlinson into keeping their relationship secret, so as not to disappoint their fans. It’s just as likely that the management are happy with the development of this subculture, as it sustains the market on which they can sell the records and merchandise over which they do exercise intellectual property rights. The situation is different for the band members themselves, who clearly find the whole thing quite traumatic; it’s changed the way they behave in public.

The text used as the catalogue essay for Common Property reflects on the relationship between fame and the market. It’s an extract from Cory Doctorow’s Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (2014), a kind of self-help textbook; a primer in ‘the critical skills required to have a non-zero chance of making a living today’ which gives a potted history of copyright laws before arguing for their reform. Doctorow’s central insight is that ‘we can’t stop copying on the internet, because the internet is a copying machine’. Many of the other works in Common Property riff on this essential idea. Antonio Roberts’ Transformative Use, a work commissioned for the show, takes on some of the most powerful and litigious copyright holders in the world, Walt Disney (the catalogue’s typeface riffs on Disney, too). Roberts also has works in the show which start with songs famously involved in copyright infringement cases, and runs them through purpose-built software: a copying machine of sorts. According to the first hit on Google,

A derivative work is transformative if it uses a source work in completely new or unexpected ways.

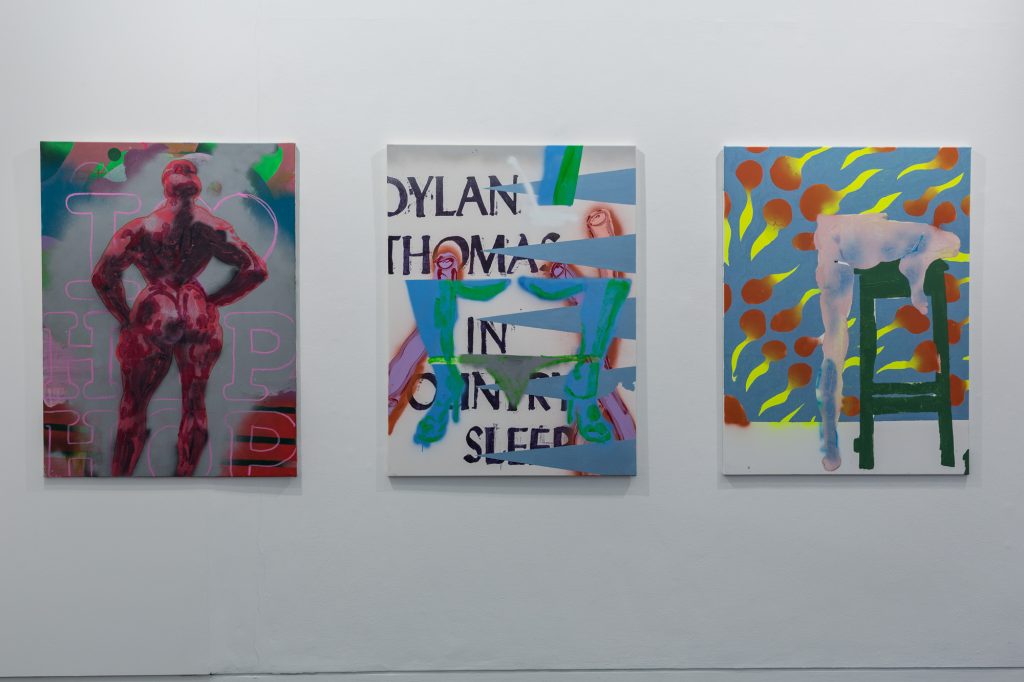

Something similar is going on in Edwin Burdis’s POLYTUNNEL-BANGERZ, a series based around the sampling ethos which came out of hip-hop: copying elements of pre-existing music and combining them into something new. Doctorow in fact talks directly about how this technique became enormously popular with Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back and the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, and then was massively curtailed by copyright law. If Paul’s Boutique was made now, clearing the samples would have cost $19.8 million. The same is true of imagery: John Berger’s collaborative TV series on the work of art in the age of photographic and televisual reproduction, Ways of Seeing (1972), can’t be released on DVD because it contains so much uncleared imagery of artwork. Burdis’s paintings in Common Property have probably transformed their sources enough avoid prosecution.

The same is true of Hannah Knox’s wall-sized installation Reproduction (2015). The technical term for a magic eye picture is an ‘autostereogram’, and specific examples of achieving the effect are copyrighted. Knox’s work plays at the legal boundaries of what’s possible, partly through her own autostereograms, and partly through painted clay urns which seem to steal from the Han Dynasty vases Ai Wei Wei variously overpainted, smashed, and branded with the Coca-Cola livery.

But as the exhibition’s curator Hannah Pierce points out in her introduction to the catalogue, it doesn’t always come off: the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans recently lost a lawsuit against the photographer Katrijn van Giel, whose work he had copied. Tuymans attempted to defend himself by pointing to his parodic intent; the judge ruled it was too humourless to count. Perhaps this exhibition about the relationship between art and law is necessarily also about the relationship between critical appraisal and law.

Katrijn van Giel is an individual. Cory Doctorow makes a distinction by arguing that giving in to the demands of large copyright-holding corporations amounts to allowing censorship to be established – a point also made by the black rectangles on Guarana Power, the work by the collective SUPERFLEX which led to Copy Right (2006), their work in Common Property. From here, he argues that such censorship can’t be achieved without allowing what is essentially wholesale surveillance of everyone on the internet.

The full phrase used in the title is ‘Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free, People Do.’ Doctorow dismisses the critique of everyday internet use as merely about wasting time chatting and social media: these are deeply human, important activities.

But as much as anything else, Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free is Doctorow taking his own advice: a kind of autobiography and advert for the author’s previous work – perhaps most famously the Boing Boing website – and a platform for it in the future. And this is maybe where we get the closest to the separation between fame and intellectual property involved in the Larry phenomenon. Really, it’s a baroque illustration of Corey Doctorow’s dictum ‘fame won’t make you rich, but you can’t get paid without it’. Fandoms and shipping might not make One Direction or their management any money directly, but they help create the necessary conditions.