She assures me they can’t fall, but I’m not convinced. In fact, Heike Brachlow’s new glass works make me decidedly nervous. Inspired by balancing toys, her chunky yet carefully poised sculptures appear extremely vulnerable; one false move by a careless visitor and these substantial coloured glass forms could be dashed into a thousand shards.

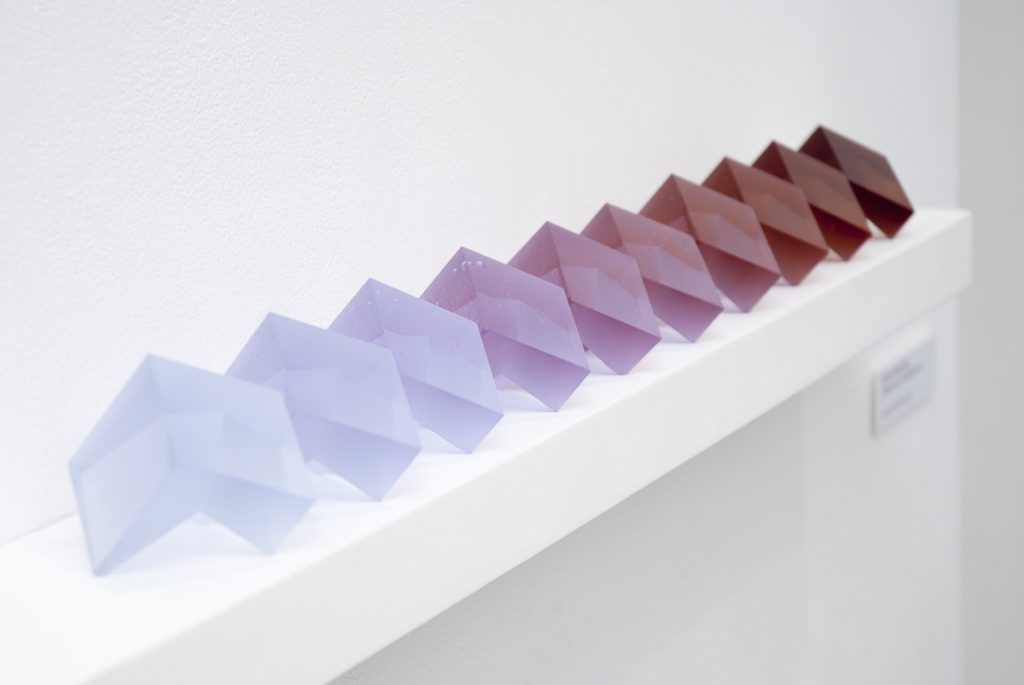

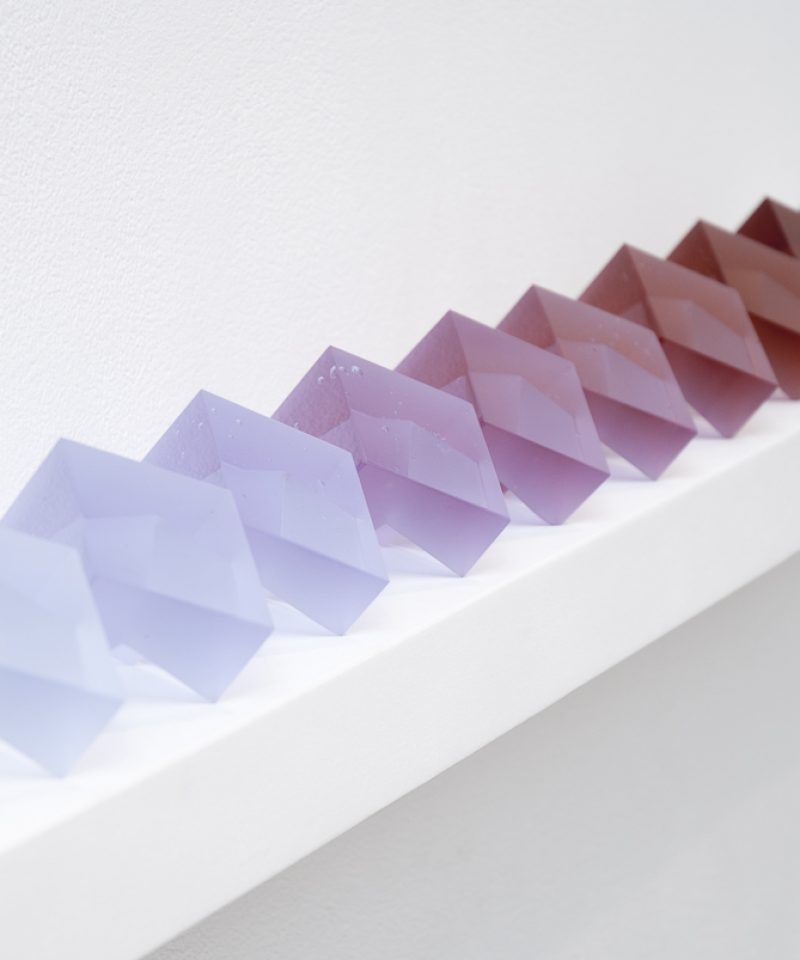

Brachlow is passionate about glass. She is also passionate about colour. Her recently completed PhD at the Royal College of Art explored innovative new ways of making transparent coloured glass and it is this period of intense practical research that has informed her work for the Jerwood Makers Open. During her studies, Brachlow developed a special technique allowing her to melt small amounts of coloured glass in a kiln. Themes and Variations I, which is presented in the Jerwood Arts alongside her new works, is a modest example of these earlier experiments. Lined up on a small shelf is a variegated sequence of glass cubes. Each piece is coloured with a slightly different hue, which together form a scintillating sweep of gradating colour, from misty blue through to rich crimson. However, when illuminated by florescent light, the colours are transformed into vibrant hues of green.

Far more ambitious that this is Brachlow’s Six Impossible Things series. Balanced on the end of slim metal poles protruding from a table-like plinth are three hefty glass forms. Coloured with subtle shades of purple, Avis I and Avis II comprise circular wedge-like forms, while between these, appearing like an oversized arrowhead, is Somewhere I, which points towards the gallery’s ceiling. Seeming somewhat precarious, these three works sway gently on their stands. As with Themes and Variations I, the colours of these works change subtly throughout the day in relation to the light conditions. Nearby, looking even more vulnerable is Avis III; hung on a free-standing pole is another circular wedge but here it is coloured with a striking electric blue. It’s works like these that are the stuff of gallery invigilators’ nightmares.

But balance is key here, and though Brachlow’s works appear very vulnerable, they are in fact a lot safer than they look. Careful choice of form and weight distribution allows the objects to remain safely balanced while simultaneously being able to move freely on a single pivot. This is achieved simply by placing the centre of gravity below the pivoting point. Nevertheless, breakages are still possible and, as Brachlow reminded me, all glass objects are vulnerable and in danger of breaking if they are knocked or dropped. This then is the tension at the heart of the artist’s new works and it is precisely this state of fragile equilibrium that makes them so compelling.