Rachel Pimm is exhibiting at Jerwood Visual Arts, alongside Katie Schwab and Lucy Parker, as part of the Jerwood Solo Presentations (27 July – 28 August 2016). Pimm’s moving image installation in Gallery Two relates to her studies into the proximity of plastics and water. Her artistic practice oscillates between performance, sculpture and video, investigating the fluid concepts of ‘naturalness’ and ‘artificialness’ in relation to subjects such as eco-design, manmade materials, and their natural and chemical histories and applications.

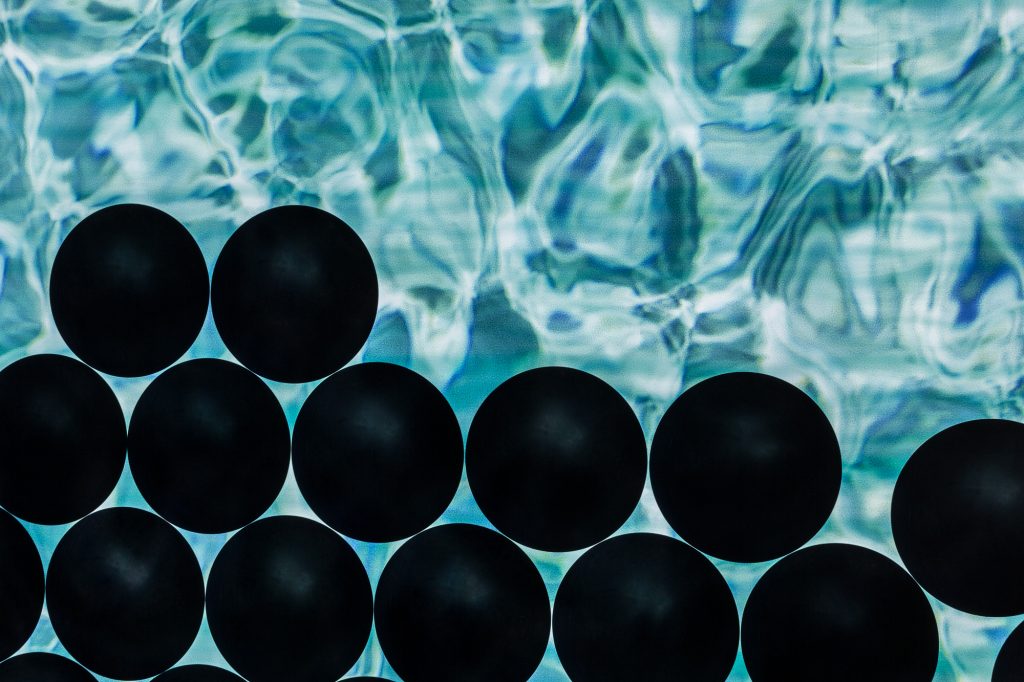

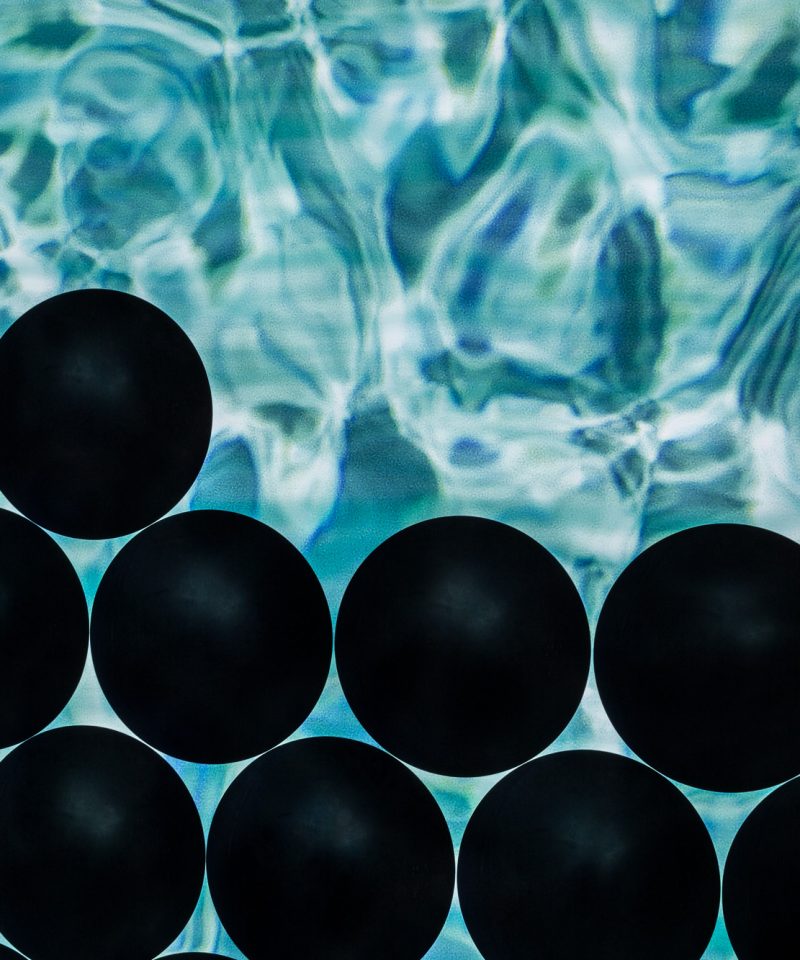

Pimm’s installation, significantly the HD video Macrobeads, explores the conflicting environmental discourses surrounding plastics in bodies of water – the use of plastic microbeads in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries, with images from government drought responses and the deployment of millions of plastic spherical shade balls into the drinking water reservoirs of California to reduce evaporation and control ecology. Micro-beads are synthetic particles, often manufactured as beads, flakes or fibres, and commonly used in cosmetics and as mild abrasives in facial scrubs, shower gels and toothpaste. A tube of face wash is likely to contain up to 360,000 of these tiny plastic spheres, which are then unwittingly released down the plughole and into the environment, wreaking havoc on ecosystems and marine life. As a consequence to their presence in water filtration systems, rivers, lakes and oceans, marine life and natural sediments ingest them. Due to the natural food chain, it is likely then that these micro-beads will also be ingested through human produce. According to a recent study by Greenpeace East Asia, 170 types of seafood contained traces of micro-plastics. Last year, Los Angeles attempted to curb the effects of the California drought. They dumped 96 million black plastic balls in the LA Reservoir to slow evaporation of the quickly dwindling water supply. They were also designed to form a cover and protect the water from UV rays and algae. Due to the typical negative connotations between plastic and water, it was particularly interesting that shade balls were seen as a solution to a problem, rather than the cause. However, according to an article on Grist, “most plastics leach endocrine disrupting chemicals that interfere with animal and human hormone systems … We don’t know what chemicals are in the shade balls, but they will leach, especially because the balls are in the hot sun and are meant to be left in the water over a long period”. Also, ironically, “over time, they fragment into tiny micro-plastics”. So, alongside causing new bacterial forms, the ‘macro’ shade balls actually have the potential to fragment into smaller and smaller, dangerous ‘micro’ beads.

These factual events are interweaved by Pimm using the motif of the black circle (an ‘O’, a full stop, the dot dot dot, a black hole) and an interest in the artistic connotations of grammar and rhetoric. The works are titled Aposiopesis (meaning: the rhetorical technique of suddenly stopping mid-sentence) and Interpunct (meaning: a punctuation between words). Pimm has also created an environment evocative of a spa, with a central pool-style lightbox. The sound of irrigated water is on a short, almost jarring, loop. The notion of the spa as a soothing sanctuary deliberately contrasts with Pimm’s evocation of urgent ecological and environmental concerns. However, I found other subtle connotations with the origins of the spa, particularly the significance of water or medicinal baths, throughout history. The practice of travelling to hot or cold springs in hopes of affecting a cure of some ailment dates back to pre-historic times. Many believed that bathing in a particular spring, well, or river resulted in physical and spiritual purification. In the medieval age, illnesses caused by iron deficiency were treated by drinking ‘chalybeate’ (iron-bearing) spring water. In 1596, William Slingsby discovered a chalybeate spring in Yorkshire, building an enclosed well, which became known as Harrogate.

In the gallery on Thursday 11 August, I heard Pimm speak with Zoe Laughlin, the director of the Institute of Making and the Materials Library project. The critic and curator Chris Fite-Wassilak (who was the Writer in Residence at Jerwood Visual Arts in 2011) chaired the conversation. Laughlin holds a PhD in Materials: Division of Engineering from King’s College London. Working at the interface of science, art, craft, and design of materials, her work ranges from formal experiments with matter to consultancy or large-scale public exhibitions and events. The Institute of Making functions as a multidisciplinary research club. At the heart of the institute is the Materials Library; “a growing repository of some of the most extraordinary materials on earth, gathered from sheds, labs, grottoes and repositories around the world. It is a resource, laboratory, studio, and playground for the curious and material-minded to conduct hands-on research through truly interdisciplinary inquiry and innovation”. Laughlin explained that the Materials Library was deliberately a ‘library’ and not referred to as a ‘museum’, due to their dedication to flux, change and creating a continually re-arranging collection. Another comment that she made which particularly struck me was about giving these materials agency, to think about “how to best let the material speak and reveal something about itself”. The audience were encouraged to refigure their conceptions about the agency of materials and how they perform in everyday life. For example, we began to think about how the material of our chairs were working; how the intrinsic components of wood meant it was able to hold our weight, where another material wouldn’t be able to.

Although the chair analogy might be simple, it exemplifies how mankind’s disregard for the importance and agency of the materials they use can have more global and widespread ramifications. Laughlin highlighted that there has been no ethical framework for humans to follow in terms of how they (mis)use materials, which has been detrimental for the environment and society. In keeping with this idea, Pimm mentioned that her recent practice has been particularly inspired by the philosophical and political project in Jane Bennett’s 2010 book Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. In the preface, Bennett postulates on how matter is conceived as “as passive stuff, as raw, brute or inert … [encouraging] us to ignore the vitality of matter and the lively powers of material formations”.[1] She continues,

“The political project of the book is, to put it most ambitiously, to encourage more intelligent and sustainable engagements with vibrant matter and lively things. A guiding question: How could political responses to public problems change were we to take seriously the vitality of (nonhuman) bodies? By ‘vitality’ I mean the capacity of things – edibles, commodities, storms, metals – not only to impede or block the will and designs of humans but also to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own. My aspiration is to articulate a vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans to see how analyses of political events might change if we gave the force of things more due. How, for example, would patterns of consumption change if we faced not litter, rubbish, trash, or ‘the recycling’, but an accumulating pile of lively and potentially dangerous matter?”[2]

Bennett’s advocation for the ‘vitality’ of matter and materiality is to do with promoting greener forms of human culture, “my hunch is that the image of dead or thoroughly instrumentalized matter feeds human hubris and our earth-destroying fantasies of conquest and consumption … The figure of an intrinsically inanimate matter may be one of the impediments to the emergence of more ecological and more materially sustainable modes of production and consumption.”[3] Pimm commented to Laughlin that she was particularly interested in what happens when you put two materials or structures side by side. The notion of performativity, or the latent agency of materials or matter, is particularly key to Bennett’s vision of ‘lively things’; “we need to cultivate a bit of anthropomorphism – the idea that human agency has some echoes in nonhuman nature – to counter the narcissism of humans in charge of the world.”[4]

[1] Jane Bennett, ‘Preface,’ in Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Duke University Press, 2010, p vii

[2] ibid, p viii

[3] ibid, p xi

[4] ibid, p xvi